I was the warm-up act this week at the University of Lincoln’s conference titled ‘Rethinking Early Photography.’ This excellent conference was an appropriate venue to try to put to rest a continuing controversy; additionally, I hope that my brief talk served to demonstrate both diverse archival research techniques and some context relevant to the Catalogue Raisonné.

I was the warm-up act this week at the University of Lincoln’s conference titled ‘Rethinking Early Photography.’ This excellent conference was an appropriate venue to try to put to rest a continuing controversy; additionally, I hope that my brief talk served to demonstrate both diverse archival research techniques and some context relevant to the Catalogue Raisonné.

Lincoln filmed the talk and expects to put this online in the coming weeks on their website. There may be a future publication stemming from it as well, but for more immediate purposes I thought that I would summarise the main findings of my research here.

This story began with an unpaid little essay that I contributed to a Sotheby’s catalogue in 2008. As had been their custom, they had rung to ask if I had any more information about a ‘Talbot’ photogenic drawing that had been brought in for sale. When I expressed my opinion that, lovely as it was, this negative of a leaf was not in fact by Talbot, it shocked both the auctioneers and their client. All three of them were people with long and extensive experience with photographs, so I was intrigued by their almost chorus-like response along the lines of ‘if it wasn’t by Talbot, then who could it possibly be?’ The Leaf was clearly early but even in the first months of photography there were multitudes of people anxious to try out the new art. Most of these people and experiments we will probably never know.

My brief little text (which prior to the present one was the one and only piece that I have ever published on The Leaf) was headed by the bold title of ‘Unknown Photographer.’ In it, I tried to lay out the various speculative possibilities, ranging from the compiler of the 1860s album in which it was found back to Thomas Wedgwood late in the 18th century. Sadly, surprisingly, maddeningly, although my attribution was clearly to an ‘Unknown Photographer’ and my text was intentionally tentative, somehow the press seized on the possible connection with Wedgwood and a worldwide frenzy of speculation followed, much of it pivoting on imagined market value. Even more surprising was the variety of responses from within the academic community, for while many were intrigued and open-minded, quite a number of scholars clearly felt that their own personal canon or nationalist interest was under threat.

One repeated ‘expert’ opinion was that no unfixed image from Wedgwood’s period could possibly have survived for more than a few days, based on a too-literal reading of Humphry Davy’s lament that ‘nothing but a method of preventing the unshaded parts of the delineation from being coloured by exposure to the day is wanting, to render the process as useful as it is elegant.’

Yet we know that some of Wedgwood’s examples lasted nearly a century, at least to 1885. There is no chemical reason why carefully stored (or resolutely ignored) Wedgwood’s could not last for a very long time. The late Terry King made a Wedgwood-o-type on a piece of chamois leather in 1989. I first saw it in 2005 when he brought it to a lecture I gave on Wedgwood at the Royal Institution, where it was passed around the room. Above is the state it was in when I last saw it in 2010, granted, only just at the age of majority then, but still far from ephemeral. To me, part of the joy of researching early photography is the ever-present possibility that there might be something new and unexpected just around the corner. One opens each dust-free package in an archive or box in the dusty attic of a family collection with continuing hope that the contents will contain a surprise, and every once in a while that expectation is amply rewarded. There is so much that we have yet to learn.

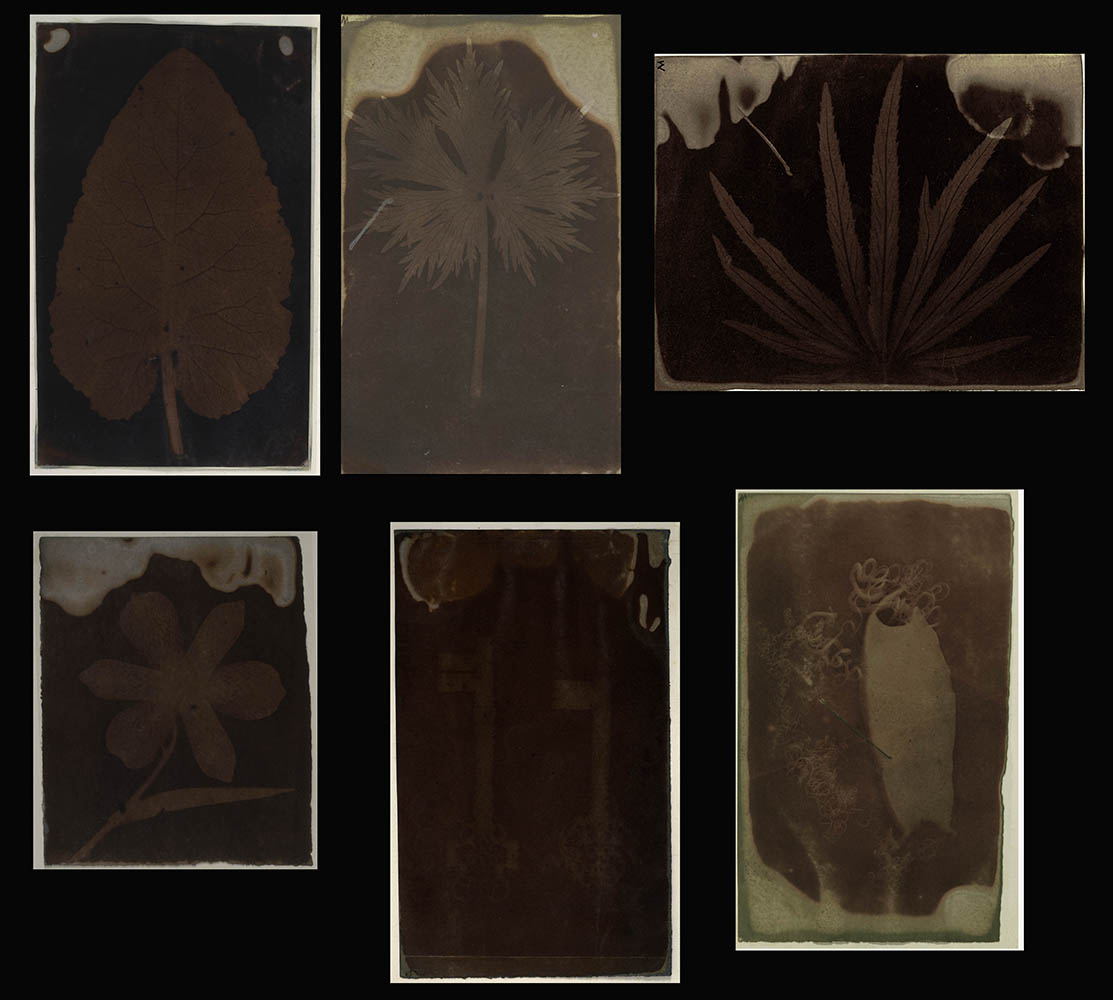

The Leaf was first sold at a Sothebys London auction in 1984. It was one of seven images mounted on an album page extracted from what was considered to be a typical miscellaneous 19th century album. The owner had consigned the album to the paintings department, who cut out the watercolours of interest and almost as an afterthought passed along the photographs to the relatively young department handling these. With the balance being seen as having no commercial value, the carcass of the album and other pages were discarded. All of this was very common practise at the time. Happily, the photographs department reproduced the original page of the very early photographs before it was cut up, so we have a record of the immediate context of The Leaf, although the broader structure of its parent album was irretrievably lost. With little to go on, the seven early photographs were attributed to Talbot.

Six of the seven images were photogenic drawing negatives that were clearly related and subsequent sales placed two of these in the J Paul Getty Museum, one in the Gilman Paper Company Collection (now with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) and the remaining three in different private collections. The Leaf was acquired by the New York based Quillan Collection . The only one to get any public display was an enigmatic picture of a shark egg casing, a curiosity meriting inclusion in the 1993 exhibition of the Gilman Collection, where its attribution was wisely refined from Talbot to Anonymous. The potential light sensitivity of this early example was recognised and a clearly labeled but a respectfully framed facsimile stood in for it in public exhibition (it was one of the first times that a major museum had employed such a facsimile, a brave move and a very astute one).

The unexpected and unwelcome media firestorm that resulted from the 2008 catalogue essay soon raised enough doubts that The Leaf was withdrawn from the sale. I believe that it still remains in the Quillan Collection – I have not seen it since the weeks before the auction.

When The Leaf was consigned for sale in 2008 it came with very few clues as to its origin. Although the original catalogue identified the compiler of the album as the watercolourist Henry Bright, the consignor soon corrected this to Henry Bright (1784-1869), a former MP and merchant who came from a prominent Bristol family. There were two inscriptions on the negative, an ink ‘W’ on the recto (inexplicably considered to be an ‘N’ in the original auction catalogue) and a completely indecipherable pencil scribble on the verso. That and the knowledge of who originally assembled the album was all there was to go on.

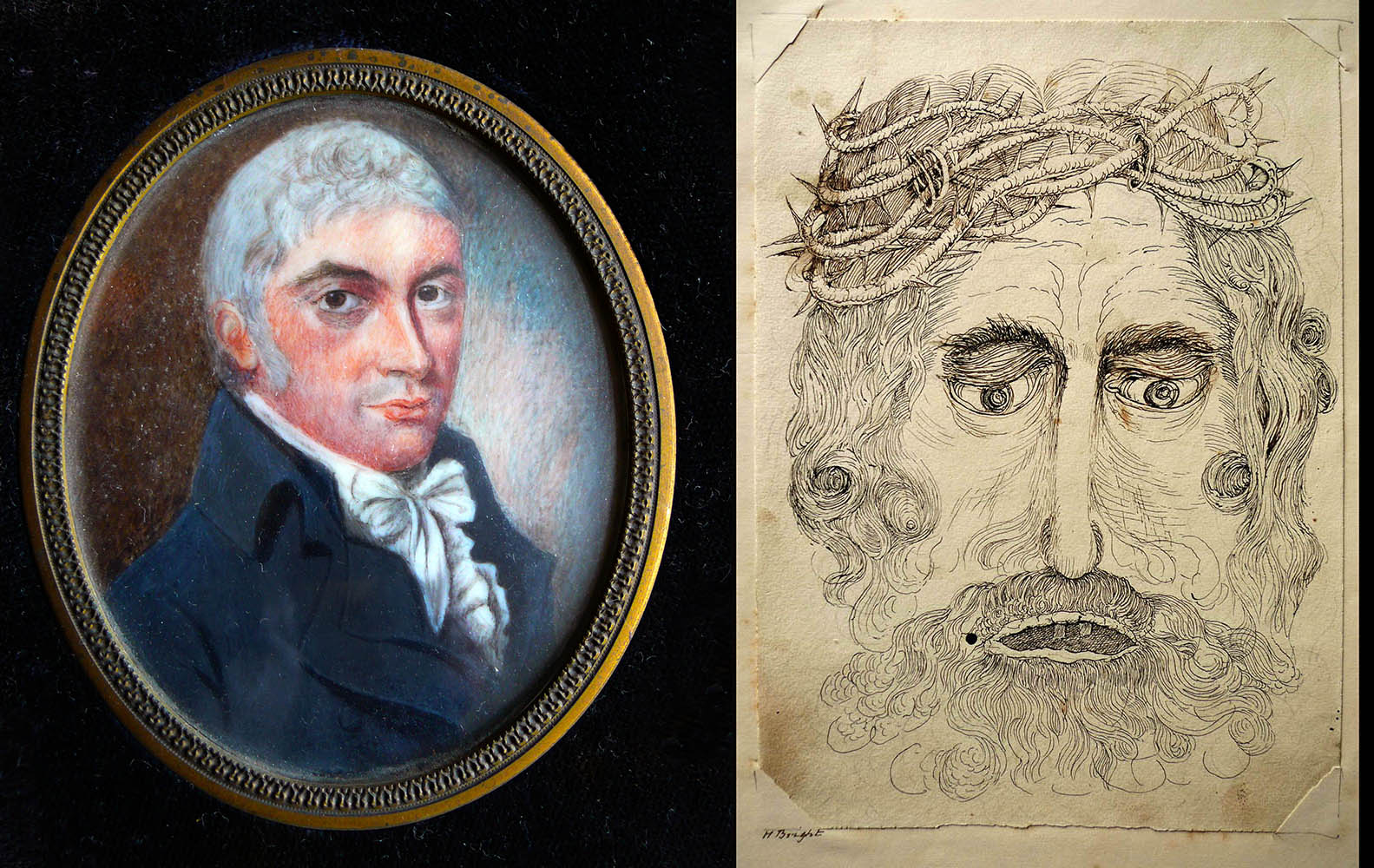

The Bright family of Bristol was a tremendously important and wealthy one, having made its fortune in the slave trade, India dealings and ultimately banking. The patriarch for our period was Richard Bright, snr (1754-1840), a merchant and banker but also a keen amateur man of science. He worked closely with the likes of Joseph Priestley and Humphry Davy and had met with Benjamin Franklin in Paris. Bright set up a chemical laboratory at Ham Green House, overlooking the Avon not far outside Bristol (now a medical centre, but largely unchanged outside). He appeared to be an ideal candidate either as one who had collected The Leaf, or as a scientific experimenter who had made it. His eldest son Henry, the one who compiled the album, was a bit more eccentric, perhaps hinted at in his self portrait above. At one time an MP for Bristol, he ‘had a turn for science and was a collector.’ In later years his nephew recalled a ‘very polished and refined old gentleman and a keen geologist’ who ‘always dressed with extreme shabbiness’ and ‘was arrested in his own garden as a suspicious character by a zealous member of the then newly-established police force.’ Henry was a passable artist himself, enthusiastic about botanical and geological subjects – was he our photographer?

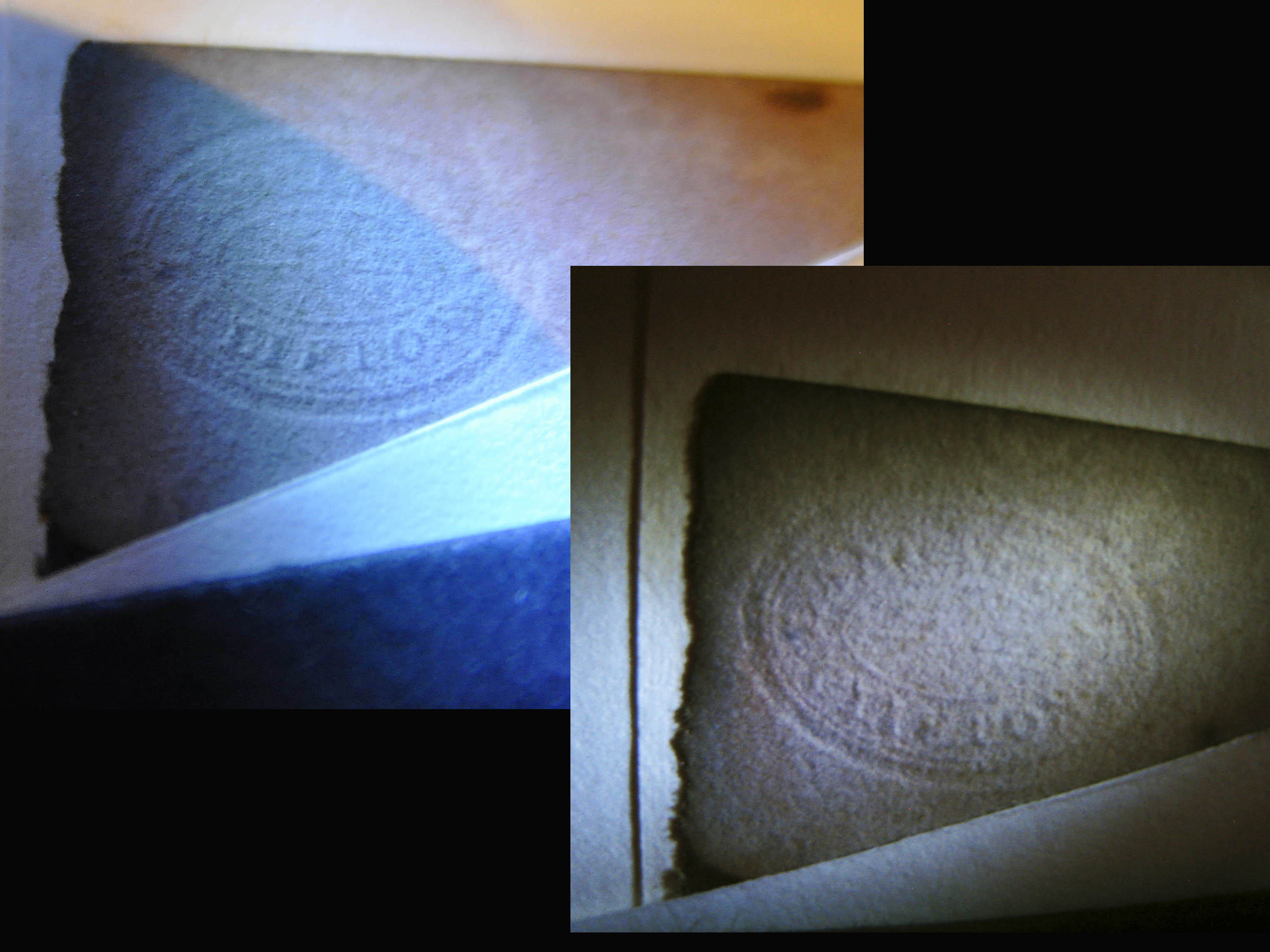

Some weeks after the 2008 catalogue was issued a critical new piece of information was revealed by one of the private owners of another of the six images. He had detected a stationer’s blind stamp on his example and its content immediately told me who had made the photographic paper. Because so much hinged on this one tiny little clue, the private owner very kindly made arrangements for me to view the negative. Using specially controlled lighting and masking, we photographed the blindstamp as well as we could while insuring against damage to the original. We made out ‘Lancaster’ across the top and ‘Clifton’ across the bottom. This was Thomas Lancaster (b 1801), who at one time had been in partnership with his younger brother Henry. By the time of photography, they remained friends but ran separate stationer’s shops, Henry in Bristol and Thomas in Clifton. Suddenly, these six negatives were old friends to me, for I had had their biography all along in my old research files.

Some weeks after the 2008 catalogue was issued a critical new piece of information was revealed by one of the private owners of another of the six images. He had detected a stationer’s blind stamp on his example and its content immediately told me who had made the photographic paper. Because so much hinged on this one tiny little clue, the private owner very kindly made arrangements for me to view the negative. Using specially controlled lighting and masking, we photographed the blindstamp as well as we could while insuring against damage to the original. We made out ‘Lancaster’ across the top and ‘Clifton’ across the bottom. This was Thomas Lancaster (b 1801), who at one time had been in partnership with his younger brother Henry. By the time of photography, they remained friends but ran separate stationer’s shops, Henry in Bristol and Thomas in Clifton. Suddenly, these six negatives were old friends to me, for I had had their biography all along in my old research files.

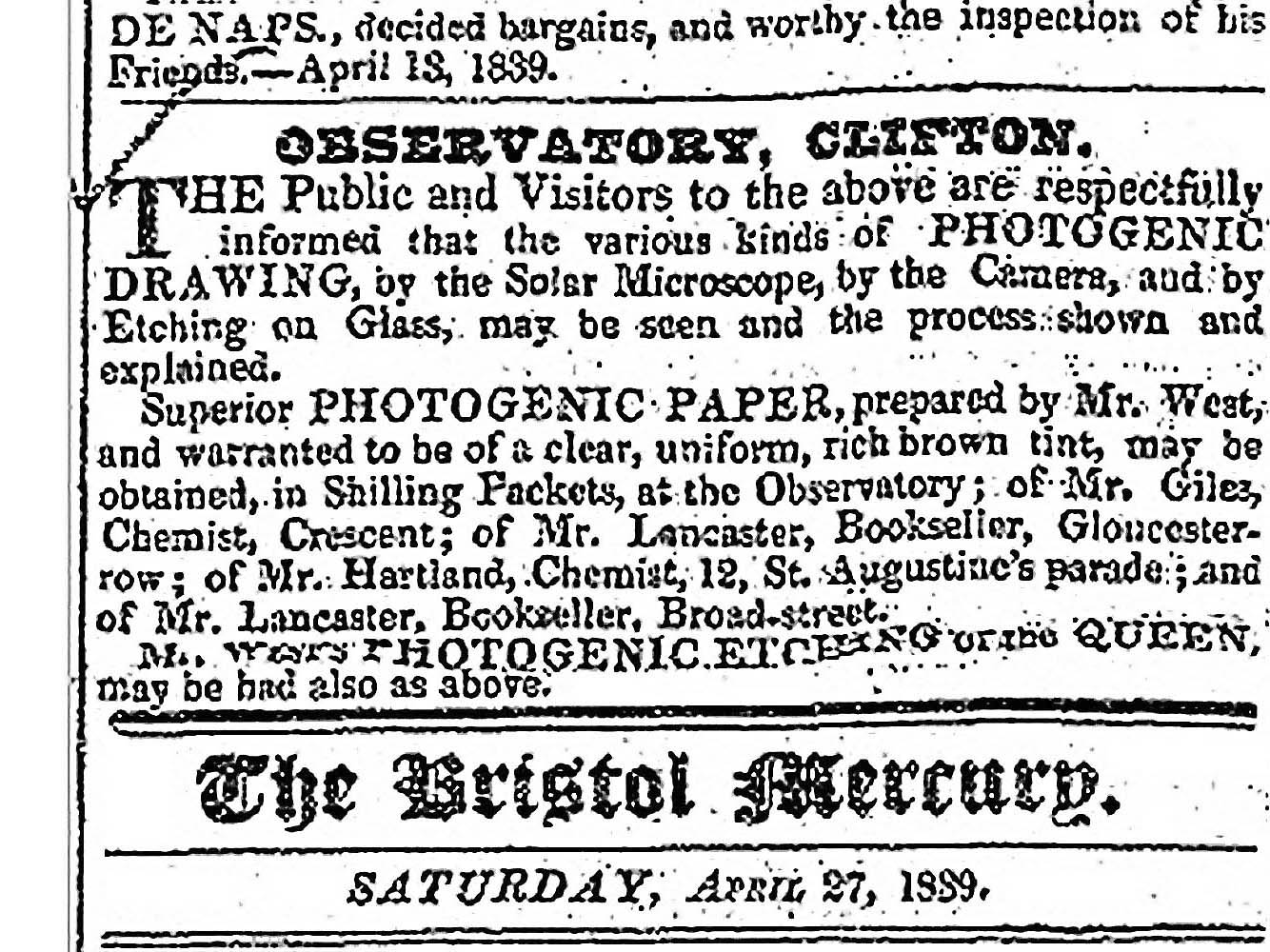

Sometime in the early 1980s I joined Mike & Barbara Gray and my wife Elizabeth in a visit to the camera obscura in Clifton, outside Bristol on the Avon Gorge. The camera was in a very dilapidated state, but the owners were very accommodating (for 40p per head, as I recall) and let us climb up the rickety stairs to view the magic scene projected on a plaster bowl (happily, there is a vigorous new ownership of the Clifton Observatory now and full restoration is underway). The Camera Obscura had been set up by William West (1798-1860) in 1828, as the central feature of his collection of scientific instruments and other manner of philosophical amusements. When Talbot freely disclosed his working method for photogenic drawing in mid-February 1839, West immediately took up the challenge and within a month was selling ready-made photogenic drawing paper from the Observatory and through the shop of his friend and neighbor, the stationer Thomas Lancaster, from whom he obtained his stocks of paper.

The meaning of the ‘W’ was immediately apparent. It was necessary to mark the sensitised side of photogenic drawing paper while it was still wet, for once it dried this was difficult to determine. Most photographers, including Talbot, settled for a simple penciled X, but West obviously saw an advertising opportunity and proudly employed his initial, marked in indelible India ink.

By the end of 1839, West was increasingly intrigued by the Daguerreotype, but in 1842 he wrote to Talbot enquiring about obtaining a license to practice the Calotype in Bristol. As far as we know, he never finalised this arrangement.

There is little doubt that The Leaf and its cousins were produced at Ham Green House sometime in the summer of 1839 – West only sold his paper that year and unused paper would not have carried over to another season. But was it done by Richard, Henry or another of his three sons, or one of his three accomplished daughters? One by one they can be eliminated. Henry himself, although a keen amateur artist, was really more of a collector, as can be seen repeatedly in surviving family albums.

There is little doubt that The Leaf and its cousins were produced at Ham Green House sometime in the summer of 1839 – West only sold his paper that year and unused paper would not have carried over to another season. But was it done by Richard, Henry or another of his three sons, or one of his three accomplished daughters? One by one they can be eliminated. Henry himself, although a keen amateur artist, was really more of a collector, as can be seen repeatedly in surviving family albums.

As it turns out, the middle sister Sarah Anne Bright (1793-1866) is the artist most frequently represented in her brother Henry’s albums. Upper left above is the inscription on The Leaf and the other three are various ways that she signed her drawings and watercolours. I think that there is now little doubt that we can add Sarah Anne Bright to our growing list of early photographers.

Nothing further has been discovered thus far about any other possible photographic contributions by her, but tantalizingly her will specifically mentions photographs, an unusual entry in a 19th c will – were these ones she collected or pioneering ones that she made?

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Catalogue of Photographic Images and Related Material, Sotheby’s, London , 29 June 1984, (there were 24 lots from the Henry Bright Collection); The Quillan Collection, Sotheby’s, New York, 7 April 2008, Sale No. 8425, Photographer Unknown, Leaf, lot 43. •Wedgwood’s process was reviewed by his friend Humphry Davy, ‘An Account of a method of copying Paintings upon Glass, and of making Profiles, by the agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq. With Observations by H. Davy,’ Journals of the Royal Institution, v. 1 no. 9, 22 June 1802, pp. 170-174. •Samuel Highley, ‘Needed, A Photographic Library and Museum,’ The Photographic News, v. 29 no. 1415, 16 October 1885, pp. 668-669. •The Bright portraits are in a private family collection. •West’s letter to WHFT can be examined in full in the online Talbot Correspondence. The portrait is a detail from a photographic copy of a now lost pencil drawing, Bristol Central Library. •The watercolour of Ham Green House and the inscriptions are taken from various of Sarah Anne Bright’s artworks in private family collections. •Sarah Bright’s will is in the Bright Archives, University of Melbourne. •Memorial window in St James the Great, Colwall, Herefordshire. •An exploration of the more than 500 identified early British photographers working with Talbot’s process can be found in the ‘Biographical Dictionary’ in Roger Taylor’s Impressed by Light: British Photographs from Paper Negatives, 1840-1860 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). While this was made as complete as possible nearly a decade ago, Sarah Anne Bright is now one of the many subsequent possible additions to this listing.