It must have been around 1973 or 1974 that I proudly took my Olympus OM1 and newly-acquired 21mm Zuiko lens on a trip to Washington, DC. Visiting the Smithsonian, I ran through a good deal of Ektachrome making slides to be used for enriching my photohistory classes at The University of Texas at Austin. Amongst the exciting exhibits was a re-creation of Talbot’s ‘Bottle Room’ at Lacock Abbey, the room above the kitchen in the Northwest corner of the Abbey. It was there that Talbot reportedly conducted many of his experiments, including those on the path to photography. Later to be the master bedroom of his son, Charles Henry, the choice of the room was almost certainly dictated by its proximity to the kitchen, for there is a persistent culinary streak running through the early history of photographic materials. The kitchen, after all, was the active laboratory of a country house and the source of heated water, numerous supplies, and chemicals such as the table salt critical to making the sensitive paper.

The 21mm lens, extraordinary for its day (I couldn’t afford the one for my Leica) was necessary to take in the full re-created room. The curved plexiglass shield interfered slightly, but the waxwork figure of Talbot remains evocative and I still use the slide today (to tell the truth, now more commonly its diminished Powerpoint spawn). In 1967, the Smithsonian’s curator, Eugene Ostroff, purchased the actual furniture and glassware from the descendants and made the room as realistic as possible. It clearly showed the delicate balance between the ample spaces of a gentleman’s country residence and the primitive, indeed domestic, physical circumstances under which great ideas were turned into physical realities.

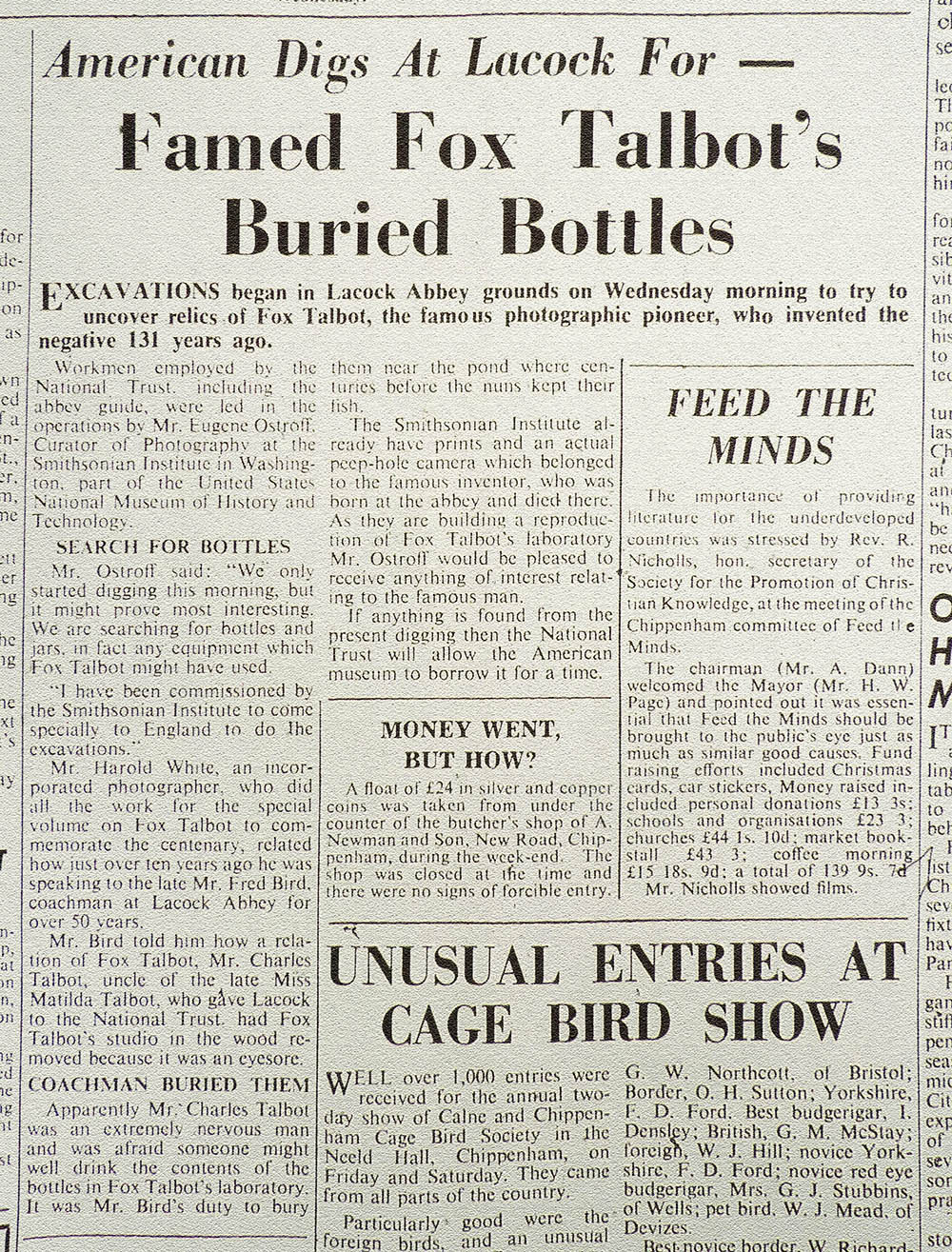

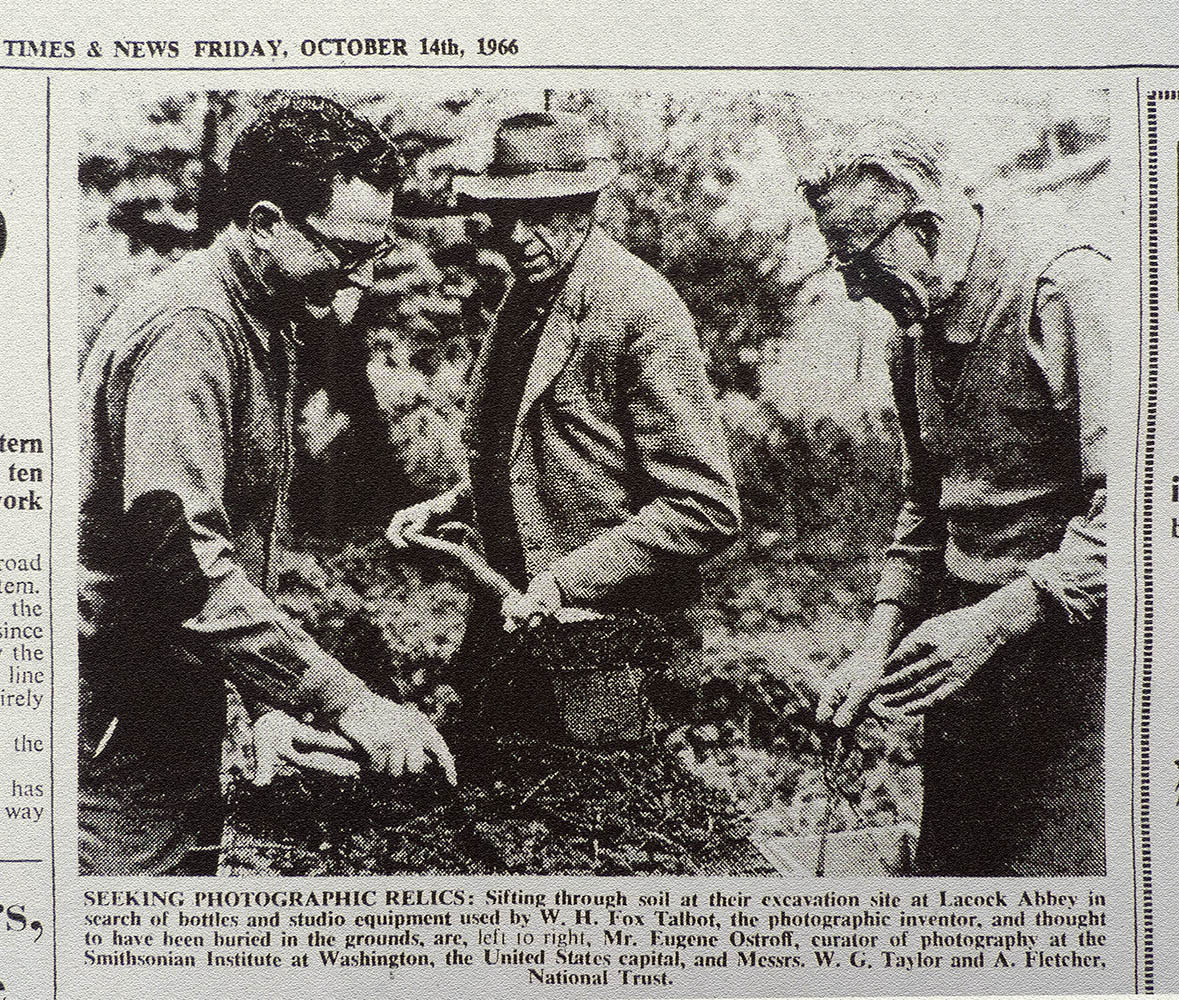

It all started with Ostroff’s interest in all matters Talbot and his efforts to catalogue the sprawling collections then at the Abbey. This campaign resulted in the well-known ‘LA numbers’, the story of which will have to wait for some subsequent posting. But on his second visit to Lacock, Ostroff acted on a story related to him by Harold White, who in turn had heard it from Fred Bird, the coachman at Lacock for nearly half a century. Out of concerns that somebody might ingest the chemicals, Charles Henry Talbot had Mr Bird bury all his father’s chemical bottles and glassware. The site for this was supposedly near the stew pond where the nuns once raised the fish for their table. After the delicate process of securing the cooperation of The National Trust, and the probably equally delicate operation of convincing his superiors in Washington that an archaeological dig at a country house in England was really a good idea, Ostroff embarked on his dream. Between 11 and 22 October 1966, he directed a small team of National Trust volunteers in a properly documented dig. (I seem to recall long ago seeing a photograph of the site being marked off in squares with string, should anybody know of a copy).

However, either the story was folklore or the site was elusive, for nothing was found. On 7 November, Ostroff was forced to report to John Rathbone, the Secretary of the National Trust, that “the investigations at Lacock Abbey failed to reveal any evidence of buried laboratory glassware belonging to W. H. F. Talbot. Even though our hopes of locating this material were unfulfilled it is my feeling that all parties concerned have done everything practicable to satisfy the annals of history.” He went on to renew the thought that a museum to Talbot should be established at Lacock Abbey.

I’m not sure exactly what Ostroff hoped to establish by any glassware that he might have found. After so many decades, it is likely that corks would have dried out and any remaining chemical residue would have been contaminated. Any paper labels would have long since disintegrated. A very few chemical bottles survived within Lacock Abbey and a couple of these have made their way into the Bodleian’s archive.

In that same archive are some excellent examples of fine glassware, the very ones that Talbot photographed for a plate in his pioneering publication, The Pencil of Nature. Some of these were recently exhibited to good effect in the Marks of Genius exhibition at the Morgan Library in New York and in the new Weston Library gallery in Oxford. These examples certainly never held chemicals (except for those of the grape), but their companions, once chipped or cracked, very likely were pressed into secondary service in Talbot’s Bottle Room.

I could not have imagined it at the time, but my 21mm generated slide of a re-creation of a historic scene has now in itself become something of a historic record. The diorama so carefully installed sometime in 1972 could not weather the changing patterns of museum management. The National Museum of History and Technology was re-branded as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Dioramas such as this went out of fashion as whole galleries transitioned over to interactive displays. In 1992, the Bottle Room was dismantled and sent off to storage in one of the cavernous warehouses in Suitland, Maryland. Personally, I think we should be mischievous and mount a campaign for its re-installation. In spite of the marvels of modern apps and digital renditions, it is difficult to conceive of a more evocative visualization of the conditions under which Talbot did his experimenting. Although Ostroff never found his bottles, Talbot’s magical process has bottled up the essence of this museum display.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Photograph in the Smithsonian by the author. • Chippenham Times & News, 14 October 1966. • The artefacts above form part of the Bodleian’s Fox Talbot Archive: the chemical bottle is FT10512 and the wine goblet is FT11204. • More about Ostroff’s activities at Lacock can be found in my “The Talbot Collection: National Museum of American History,” History of Photography, v. 24 no. 1, 2000, pp. 7-15.