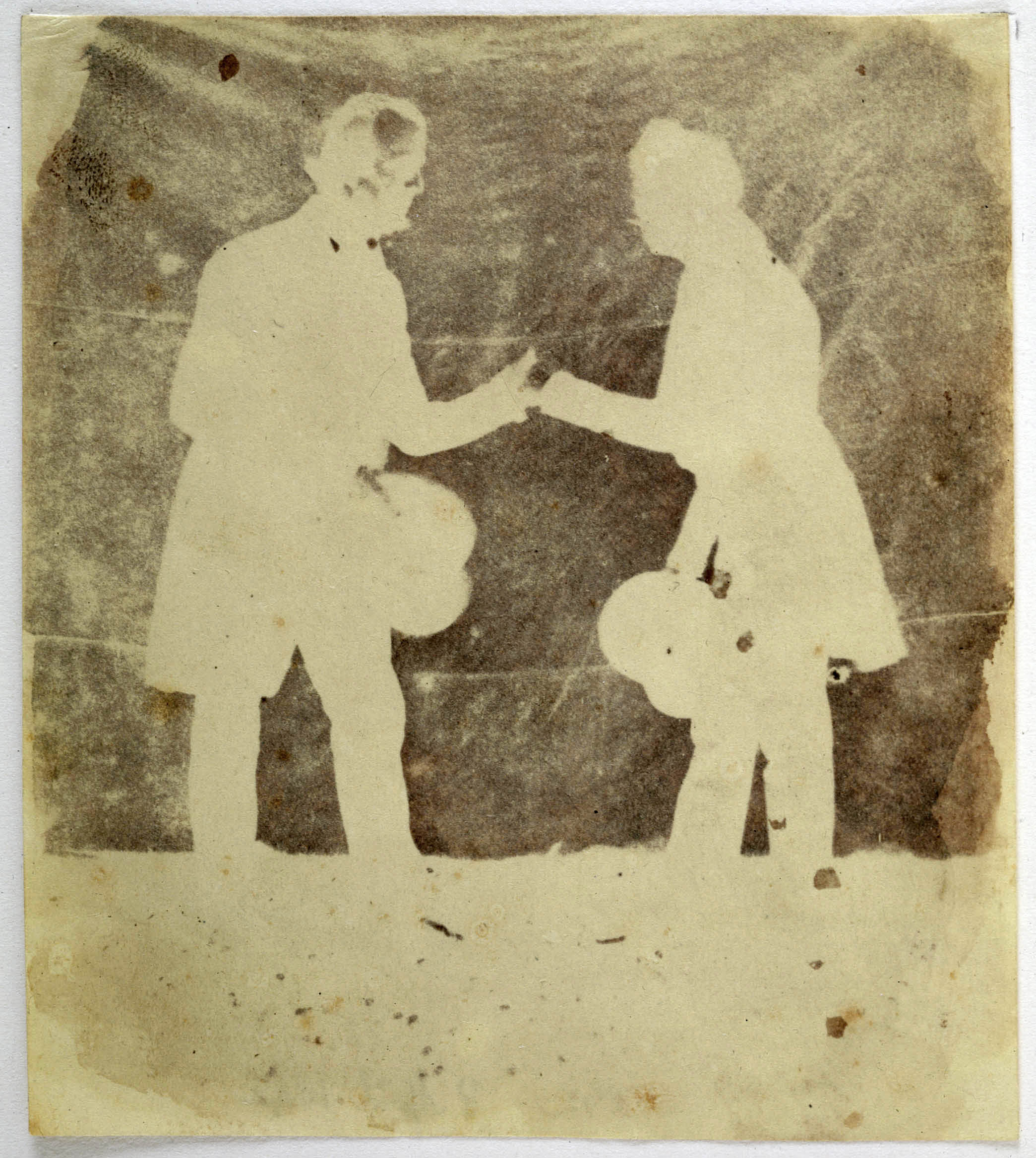

I must confess that I prefer some of Talbot’s images in the negative (as did he), so even though there are several unusually interesting prints extant from this calotype negative, I think that none can rival the sheer visual pleasure of the actual sheet of paper that faced the sunshine that day. Taken at Lacock Abbey on 8 April 1842, this photograph records a most extraordinary intersection between the worlds of the calotype and the daguerreotype. On the right is Nicolaas Henneman, still Talbot’s valet but becoming increasingly independent as photography penetrated deeper into his imagination. The following year he would leave Talbot’s employ to establish his Talbotype photographic establishment in Reading. On the left, with a massive frontal lobe that must have excited the phrenologists, is John Frederick Goddard (1797-1866). Then an operator for Richard Beard, Goddard had already made one of the major contributions to the practicality of the daguerreotype. By improving on Daguerre’s method of sensitising, he had reduced exposure times for daguerreotype portraits from excruciating minutes to mere seconds. In spite of this, he was received at Lacock not as a rival, but rather as a respected scientific colleague. Lady Elisabeth recorded in her diary that “Mr Goddard came to learn about photography” and the transfer of technologies was a mutual sharing. Talbot already knew Goddard, for they had exhibited together in Scotland in 1839, Talbot with his photogenic drawings, Goddard with his polariscope, an instrument that appealed strongly to Talbot’s long-standing scientific interest in light. Seen in partial silhouette, the two figures are like musical notes arranged on staff lines created by the sewn-together background sheet that created a temporary outdoor studio at Lacock.

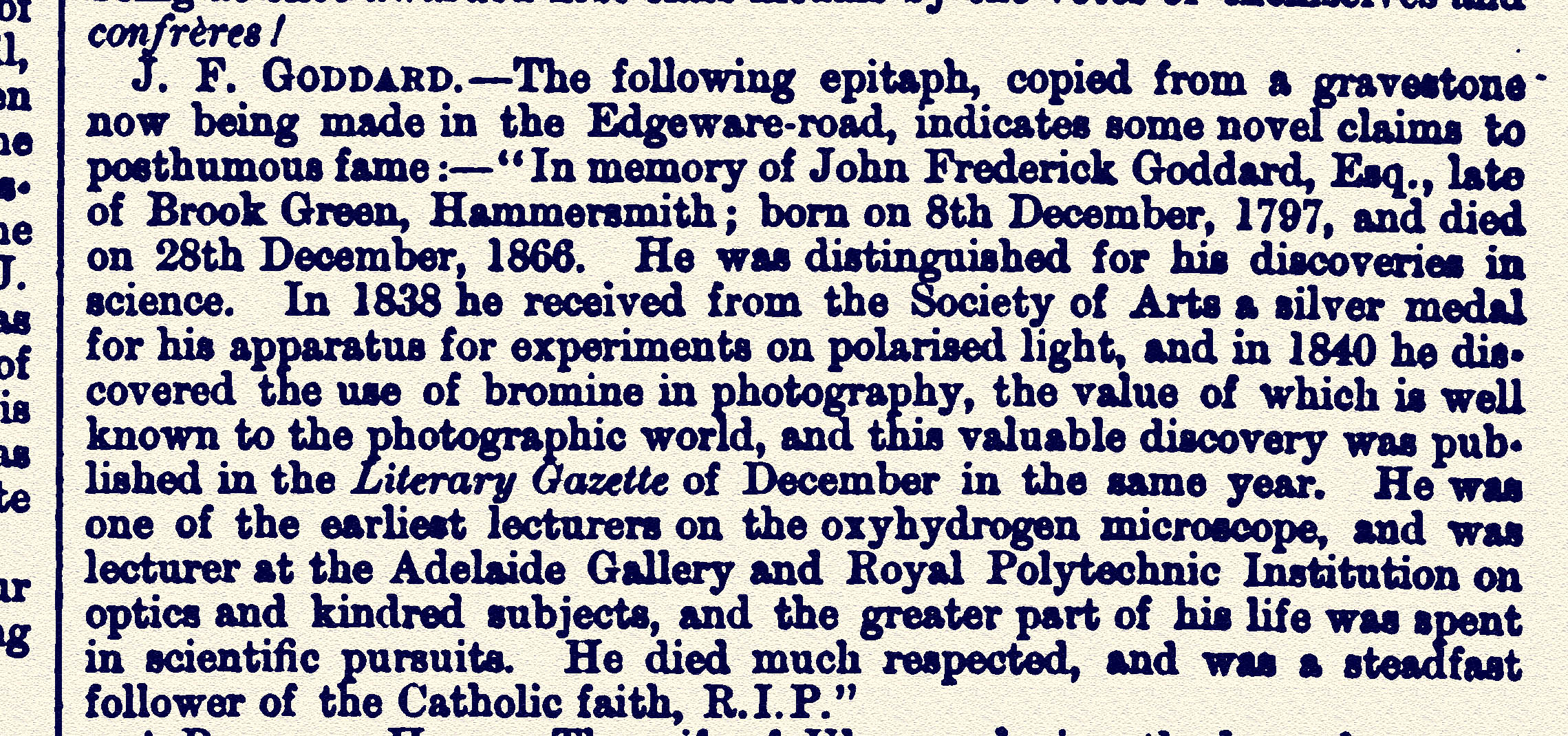

Goddard is generally mentioned only in passing, if at all, in the literature today, certainly with less detail than that of the remarkable epitaph on his tombstone. The British Journal of Photography transcribed this from “a gravestone now being made in the Edgeware-road.”

Goddard was buried in the relatively new Saint Mary’s Catholic cemetery adjacent to Kensal Green. Sadly, all cemetery records prior to 1924 were subsequently lost to an unknown cause. By the 1990s, the cemetery was becoming overcrowded and around the year 2000 the St Georges and St Mary Magdalene section where he was placed was prepared for new burials. The existing graves were not disturbed but were covered with 12 feet of topsoil. Having suffered particularly heavy erosion in this area of the cemetery, most of the grave markers and headstones were badly damaged and were ‘removed and disposed of.’ Goddard’s grave, number 9030, is indicated in red on the historical map, meaning that a gravesite was traced but the number had to be extrapolated. If the stone was still readable this would have not have been necessary. In any case, I don’t think there were any family members left to claim the stone, so its transcription in the BJP has become its memorial.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk •WHFT dated this negative in pencil on the verso; it is in The Thomas Walther Collection, reproduction courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc; Schaaf 2646. •BJP, v. 14 no. 370, 7 June 1867, p. 273. •Lady Elisabeth’s diary is in the Lacock Abbey Collection, Wiltshire and Swindon Archives, Chippenham. •One of the best prints from this calotype negative, the one WHFT sent to Dr. Carl Fredrich von Martius, is illustrated in Ulrich Pohlmann, Alois Löcherer; Photographien 1845-1855 (Munich: Fotomuseum im Münchner Stadtmuseum, 1998), plate 4. Of the other known prints, the one WHFT sent to Sir John Herschel, once in the collection of André Jammes, is now owned by the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.