There is a saying in Scotland that if you don’t like the weather, wait a wee while and it will change. By October 1844, Talbot’s personal weather was changing for the better. Gone were the storm clouds of 1839, displaced by an ever-increasing mastery of his own new art. Even though he was feeling poorly at the time, the fortnight that he and Nicolaas Henneman spent in Scotland was one of his most creatively productive periods ever.

It led to the 1845 Sun Pictures in Scotland, 100 copies with 23 photographic prints each, sold by subscription. Let’s continue the discussion started last week:

A mountain rivulet which flows at the foot of Doune Castle

A mountain rivulet which flows at the foot of Doune Castle

My friend Roger Taylor once commented that if labeled with a properly thought-provoking title this haunting 1844 Talbot image could as well have been hung in a 1984 exhibition credited to Thomas Joshua Cooper. It is timeless, location free, yet very specific about a mysterious and enigmatic place. As one examines the photograph, what appears to be a distant mountain forms into a river bank and as the looming bulk of Doune Castle becomes visible there is a dramatic shift in your perception of the scale of the trees. This is actually a larger variant of Plate 20 in Sun Pictures in Scotland. Both are good, but I have always preferred the present one, as eventually did Talbot himself. Nicolaas Henneman helpfully recorded them having boarded an omnibus in Edinburgh on 18 October 1844 and later in the day he paid a porter at Stirling. They were headed towards Loch Katrine and would have passed Doune going and returning. By 22 October they were packing up for the return to Lacock.

Doune is one of the most impressive ruins in Scotland, commanding a position high on a mound at the confluence of the River Ardoch and the larger River Teith. Older readers might recognise the castle as the main filming location of Monty Python and the Holy Grail. However, Talbot’s visit was just three decades after Sir Walter Scott memorialised it in 1814 in his first novel, Waverly. In it, the condemned Edward Waverley spotted Doune when the “half-ruined turrets were already glittering in the first rays of the sun.”

Talbot and Henneman would have had to camp out in what was very much a wilderness in order to catch the first rays of the morning sun. Even if they had attempted that, judging by the tones in his various Doune photographs Scottish weather had presented him with leaden skies rather than glittering ones that day – much the same as when my trusty Scottish guide Robert Robertson first took me to Doune. In making his photograph, Talbot wisely chose to concentrate on another of Scott’s passages, where Waverley “crossed an ancient and narrow bridge” and faced “the gloomy yet picturesque structure that he had admired from a distance.” Talbot’s photograph just hints at the gloomy and picturesque structure looming above him, soon to be the inescapable prison of the accused.

As he was heading towards Loch Katrine, the Scottish weather again changed. Suddenly the autumnal sun was brilliant. The active pose of this man, in robust good health and enjoying the sunshine, is complemented by the rich texture of the stone and the forcefully uplifting diagonal lines. His head blurs with impatience at the several second exposure. He is just possibly one of Talbot’s uncles, John George Charles Fox Strangways (1803-1859), an MP normally resident in Wiltshire. On 10 October 1844 Constance wrote to her husband, “Do tell me whether your journey has begun to do you good – I am so anxious it should independently of the Talbotypes and when shall you reach our Uncle John’s Paradise?” She obviously hoped that they could secure a place like this, for on 13 October she again wrote, “You have a nice opportunity during this tour for looking about & perhaps you may chance to meet with something attractive – I suppose Uncle John is not singular in his taste – & he has found a paradise.” (A decade later, their Scottish paradise was to be in Edinburgh and vicinity, where they took up residence to be near their grandchildren and where Talbot conducted much of his important research into photogravure).

For some reason, this photograph has repeatedly been titled “The Charcoal Burner’s Hut.” How a charcoal burner could retain the whiteness of his shirt is beyond me, but another plate in Sun Pictures gives a better perspective of the building. It is a boat shed typical of the Trossachs, much like as seen in the 1860 view on the right. Just the place to store a boat between visits to a personal paradise.

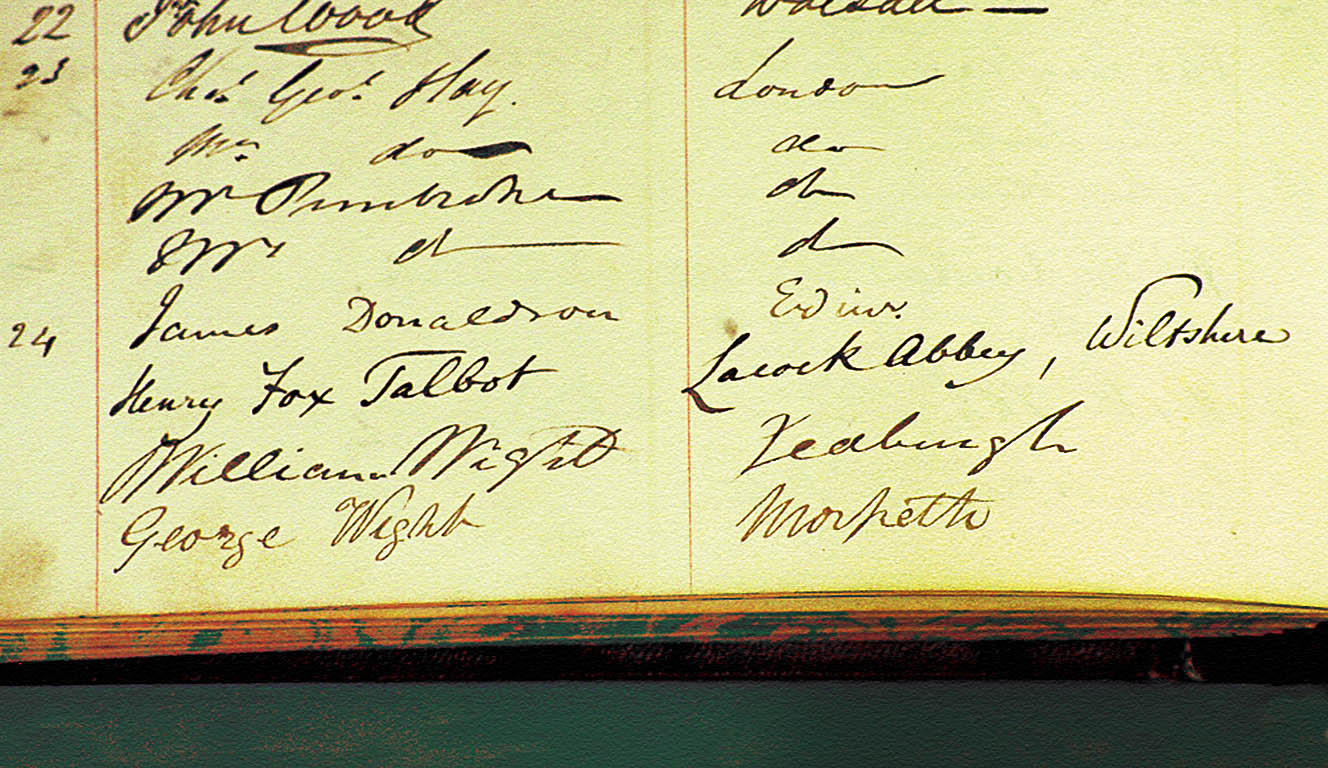

Reversing the expected order of things, Talbot and Henneman finished their trip at Abbotsford, the home of their subject Sir Walter Scott. We can date their arrival quite precisely. Some years ago over tea, my longtime friend Bill Buchanan gently persuaded the elderly good ladies of Abbotsford to bring out the old visitors books. And there, on 23 October 1844, Henry had signed his name. The other men that day have not been identified – was one possibly a travelling companion who posed at the boathouse above?

Of the several views of Abbotsford taken by Talbot, the one of Scott’s favourite dog Maida particularly stands out, providing at once an example both of the descriptive strengths of photography and the restrictions that same veracity imposes.

Effigy of Sir W. Scott’s favourite dog Maida, by the side of the hall door at Abbotsford

Effigy of Sir W. Scott’s favourite dog Maida, by the side of the hall door at Abbotsford

Scott so loved his deerhound Maida (1816-1824) that upon the dog’s demise he buried him under a statue outside the front door to Abbotsford (ostensibly as a stepping stone for his carriage), with a Latin inscription that reads in part, “sleep soundly, Maida, at your master’s door.” There is a long and bright gravel drive behind the stone statue, so Talbot hastily draped his cloak behind the dog, isolating it from the background, with only a little bit of foliage harmlessly intruding at the top.

But other more serious things were to intrude on Talbot’s plans. Sun Pictures in Scotland was delivered to the 100 subscribers in 1845, but distressingly, many of the prints started deteriorating almost immediately.

The tomb of Sir Walter Scott, in Dryburgh Abbey

The tomb of Sir Walter Scott, in Dryburgh Abbey

Paralleling the sudden and unpredictable changes in Scottish weather, most of the prints in the issued copies of Sun Pictures in Scotland have changed radically, condemning it to be one of the most under-rated of all of Talbot’s productions. Last week we saw a beautiful loose print of Dryburgh Abbey, matched this week by a more typical mounted one. Nicolaas Henneman was forced to make these prints under most unfavourable conditions in the dead of winter. His Reading printing establishment was already straining to supply prints for the Art-Union and for the ongoing fascicles of The Pencil of Nature. The prints were insufficiently fixed and washed, making them even more vulnerable to subsequent environmental conditions such as adhesives and the fumes of coal smoke. Fortunately, beautiful loose prints of most of the plates survive, preserving ting the initial power of Sun Pictures in Scotland, in my opinion one of the most powerful demonstrations of Talbot’s maturity in his own art.

I don’t know of a single copy of Sun Pictures in Scotland that is not made up of partially or totally fading plates. The sole exception is a beautiful but not quite real one where Harold White intensified the plates in his personal copy, now in the collection of the Canadian Center for Architecture.

How many of the original 100 copies of Sun Pictures survive? Somewhere in the low dozens are currently known and I always check library catalogues when visiting. They were distributed to a wide range of society figures and occasionally come up in house sales or auctions.

Do you have a copy or know of a copy? If so, please drop me a note and perhaps that will add to the census.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, “A mountain rivulet which flows at the foot of Doune Castle,”salt print from a calotype negative, 19-21 October 1844. Fox Talbot, Collection, the British Library, London, LA854; Schaaf 17. The smaller published one is Schaaf 2781. In February 1845, after receiving 300 large-size prints of “Doune Castle, different view,” Talbot loaned this negative to Nicolaas Henneman for use in his own printing; it still survives today, with four nasty spots in the stream area in the lower right retouched in pencil, perhaps evidence of why it was further trimmed after making some prints. The negative is National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1352. • See Thomas Joshua Cooper’s haunting Between Dark and Light (Edinburgh: Graeme Murray, 1985). • Notebook, Nicholls Account, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London. • WHFT, Scenery of Loch Katrine, salt print from a calotype negative, 19-22 October 1844, Michael Wilson Collection, 94:5075; Schaaf no. 2792. • Constance’s letters of 10 October 1844, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 05098, and of 13 October, Doc. no. 05102, are in the Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London. • WHFT, Loch Katrine, salt print from a calotype negative, October 1844, private collection; Schaaf 2786. • WHFT, Effigy of Sir W. Scott’s favourite dog Maida, by the side of the hall door at Abbotsford, calotype negative, 23 October 1844, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1314; salt print from the calotype negative, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc; Schaaf 2784. • WHFT, The tomb of Sir Walter Scott, in Dryburgh Abbey, salt print from a calotype negative, likely 25 October 1844, the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY; Schaaf 2801. • One of various manuscript lists of subscribers to Sun Pictures in Scotland, National Media Museum, Bradford. • For a critical analysis of this book, see Graham Smith, “William Henry Fox Talbot’s Views of Loch Katrine,” Bulletin of the Museums of Art and Archaeology, The University of Michigan, v. 7, 1984-1885, pp. 48-77.