To people in 1839, photography must have seemed so mysterious and magical that it bordered on science fiction (but rest assured, both Aphnodium and Gogar were real, as we will see). To Henry Talbot, his new art was a marvelous fusion of hard science and the lyrical hand of Nature.

Sometimes one seems to learn a great deal more by wandering off the straight and narrow. In examining Talbot’s mind and work this becomes almost a truism, for his interests were so diverse and his imagination so rich that seeking a central path is a fool’s errand. When we think about his photographs, Lacock Abbey immediately comes to mind, strongly complemented by Henneman’s productions at the Reading Establishment. However, Talbot spent considerable blocks of time north of Hadrian’s Wall. We have previously looked at his October 1844 trip to photograph for Sun Pictures in Scotland and some day we should have a go at Sir David Brewster and the fabulous partnership of Adamson & Hill.

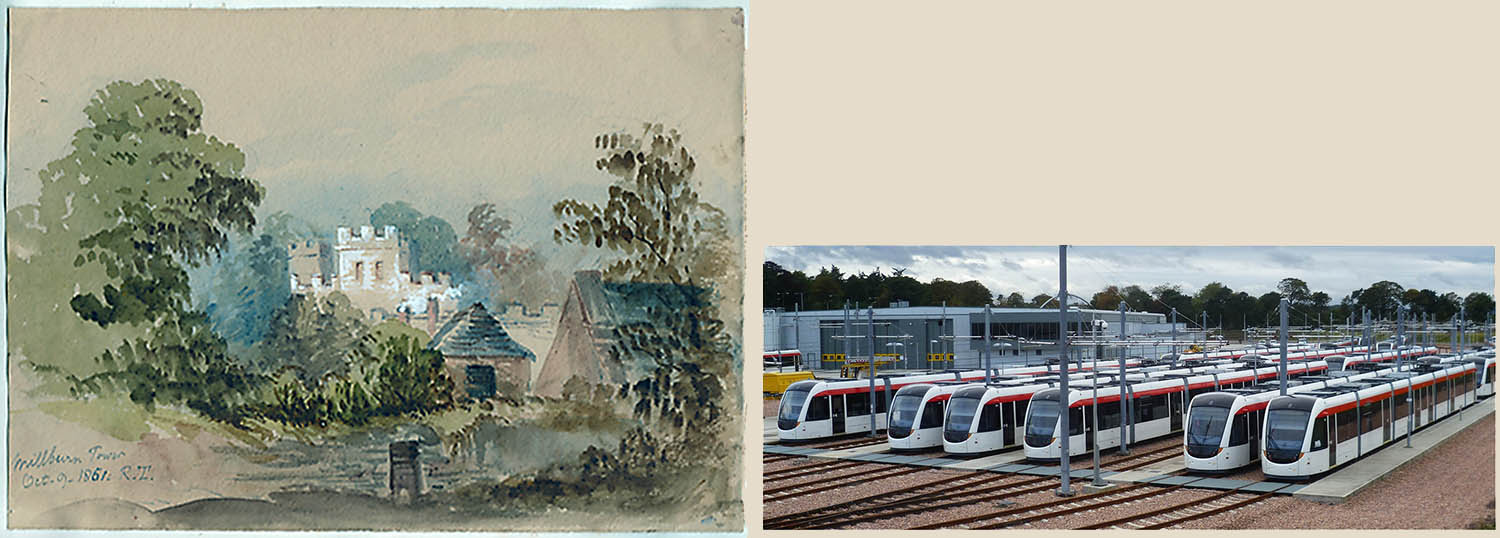

Only one of the Talbot children ever married, their third daughter, Matilda Caroline, ‘Tilly’, who was born in February 1839 and consequently was almost named ‘Photogena’. In 1859 Tilly married John Gilchrist-Clark of Dabton House, Thornhill, Dumfrieshire, a JP and Advocate at the Scotch bar. As a result, the Talbot family began spending considerable periods of time resident in Edinburgh. In the early years, they rented various houses in Edinburgh’s New Town. From late 1863 until 1871, they owned 13 Great Stuart Street in Edinburgh. However, I think that one of the most interesting periods was from June 1861 to December 1863 when they resided at Millburn Tower near Gogar, then a rural area on the western outskirts of Edinburgh and now perhaps best known as the terminus for Edinburgh’s second tram system (the first was introduced just as the Talbots were leaving Edinburgh).

Gogar in 1861 and 2012

We first learn of the Talbot’s new northern home from a 9 March 1861 letter from Rosamond Talbot to her father. She and Constance had set out from Edinburgh to visit a friend in the country, Lady Elizabeth Sarah Gibson-Craig, but finding her not at home they visited nearby Millburn Tower, then advertised for rent.

Millburn Tower, by Rosamond Talbot, 1861

Rosamond reported to her father that Millburn Tower surprised them and “proved to be a remarkably nice house in many ways, very pretty and uncommon outside, and convenient inside.” The house had a rich history. It was built for Sir Robert Liston, a native Scot, diplomat and an important figure in Anglo-American relations. A large round building proposed by Benjamin Latrobe was passed over in favor of a more modest home designed by William Atkinson, best known as the architect of Sir Walter Scott’s Abbotsford. The distinctive Gothic exterior was raised in 1815 and an additional extension built in 1821. Liston’s Antigua-born wife, the botanist Henrietta Liston, née Marchant, established bonds with George Washington and John Adams during her husband’s ambassadorship. She created a lavish American garden, sadly largely gone by the time the Talbots rented the house. The building survives and the remnants of the gardens are listed today.

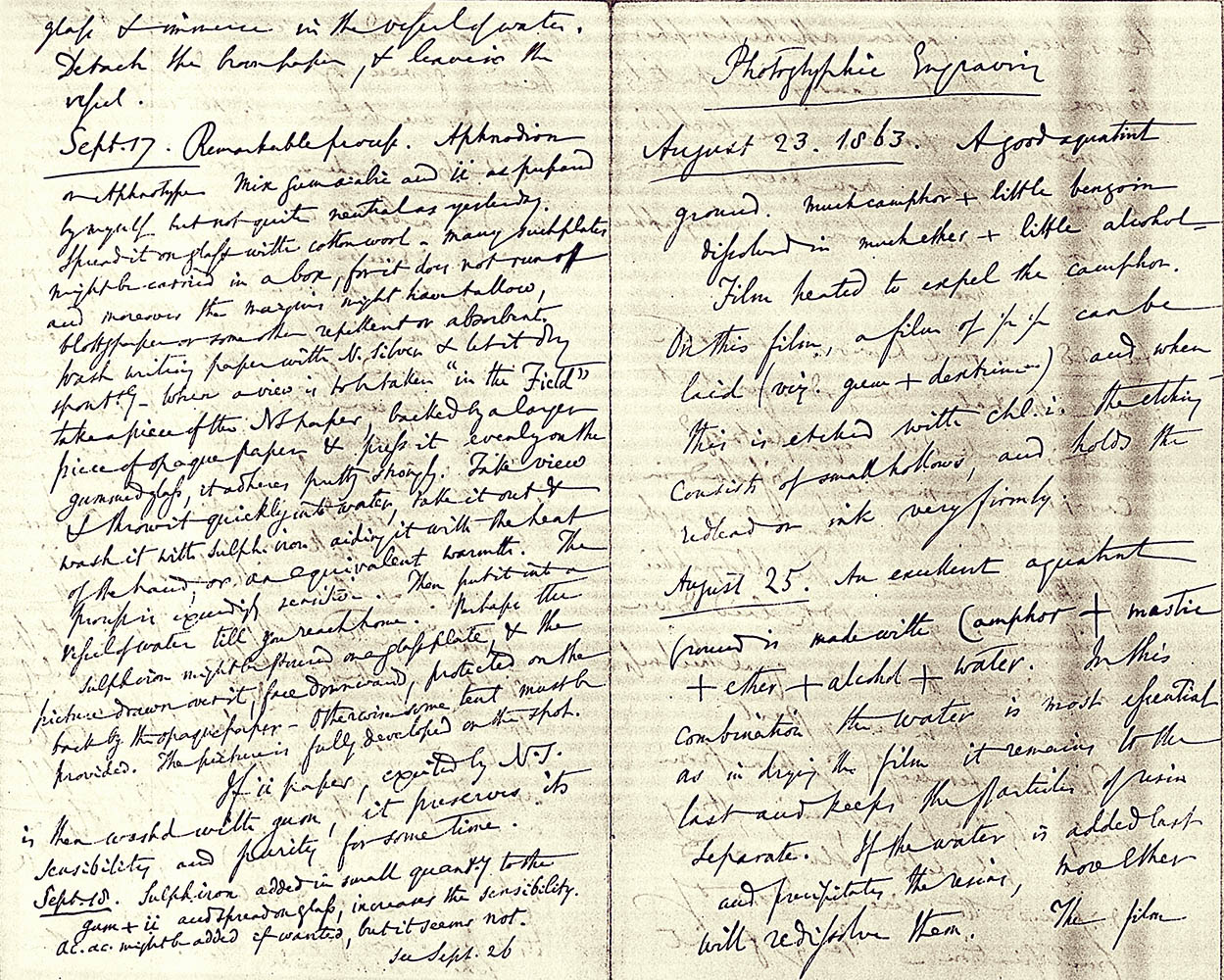

But the appealing character of the house was not all that Rosamond observed: “what would please you, Papa, beyond anything is the existence of a large empty room, separated from, though close to the house, with three south windows looking out on the garden, & a good fire-place. Just the very place for your engravings!” The reference to engravings was not to a collector’s cabinet, but rather to the extensive series of experiments that Henry Talbot had been conducting on photogravure since the early 1850s. Millburn Tower was to become an important research centre for him.

By all the visual and archival evidence that we have, Talbot gave up taking photographs himself in late 1845. He was discouraged by the fragility of the prints in The Pencil of Nature and was soon to lose his mother, Lady Elisabeth Feilding, who had been a major driving force behind his visual productions. However, Talbot never lost interest in the science of photography nor in other people’s use of it. His family members avidly collected photographs when they travelled and Talbot continued to conceive of improvements to the art.

On 17 September 1863, working at Millburn Tower, Talbot recorded a “remarkable process” which he proposed calling “Aphnodium or Aphnotype”, derived from the Greek ἄφνω, meaning suddenly or unexpected. It was a curious negative process that combined his old standbys of silver nitrate and good quality paper with a new approach. He envisioned its main use for “where a view is to be taken ‘In the Field’.” Talbot prepared two components in his laboratory. One was a batch of sheets of glass coated with chemicals trapped in gum Arabic, a moist sticky coating insensitive to light. The other was paper washed with silver nitrate and dried, also relatively insensitive to light. At the point of taking a photograph, he pressed the nitrated paper into contact with the coated glass sheet, both adhering it and setting up a chemical reaction that made a highly light-sensitive surface. Once exposed, the picture was developed immediately using a ferrous sulphate solution. Talbot even thought of the idea of backing it with opaque paper, thus doing away with the need for a dark tent, an approach that might remind older readers of how Polaroids were once developed.

I’ve never seen an identified example of the Aphnotype, but now that you are alerted to its presence, do have a close look in your collections.

I’ve never seen an identified example of the Aphnotype, but now that you are alerted to its presence, do have a close look in your collections.

The larger part of Talbot’s research during the Millburn Tower period was spent on his experiments with photoglyphic engraving, the direct forerunner of photogravure. For most of photography’s 19th century life, the ability to reproduce photographs in printer’s ink was an elusive but essential goal. In our present world of glowing screens, we are rapidly forgetting the influence that books and journals had on the dissemination of images, but until fairly recently the vast majority of photographs were seen on printed pages rather than in original prints. Talbot had that goal clearly in mind from the time that his prints in The Pencil of Nature started degrading under uncontrollable environmental influences. He sought a way to separate the two stages of the process, retaining Nature’s hand in making the original photographic image but then employing a companion method for reproducing that image, not in vulnerable silver, but rather in time-tested printer’s ink. His first experiments utilised some of his own 1840s photographs and also a return to photograms, employing botanical specimens or scraps of lace as ‘negatives.’ However, he soon turned to other photographers for a supply of the glass positives that he would use in his plate experiments. Curiously, on the whole the French understood the importance of his quest better than others and many of the original images that he used came from friends there. We don’t know what photographer supplied the original for this experimental photoglyphic engraving of Notre Dame, but the inscription is in Talbot’s hand and his dating of 1861 places it as originating from his laboratory at Millburn Tower.

Nearby Edinburgh was a powerful force in the world of printing at that time and Talbot was able to take advantage of the expertise and materials readily available there. His goal was to photographically create plates, sometimes on steel, sometimes on copper, that could be utilised by a regular printer in a conventional printing press. The firm of D & J Greig became one of his major suppliers.

It is generally believed that Talbot never made it beyond the experimental stage in his work on photogravure but that is not entirely true. There were a number of instances where he provided photoglyphic printing plates to real publications and most of these came out of his Scottish era. The eccentric and imaginative Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Charles Piazzi Smyth, accompanied by his indefatigable wife Jessie hauled a telescope ‘above the clouds’ at Teneriffe in 1856 to prove Newton’s theory that the atmosphere rather than optics would become the limiting factor in celestial observation. Theirs was the first form of the Hubble Space Telescope. When it came time to print his official report, Piazzi was rebuffed in his use of photographs by the skepticism of government officials, so Jessie made enlarged albumen prints in her own kitchen window. Knowing the vulnerability of silver prints and wanting the visual evidence of his photographs to persist into the future, Piazzi turned to his friend Talbot to provide a photoglyphic engraving plate to complement the albumen prints. Smyth was perceptive in his introduction to the volume: “To the inventor alike of photography and photoglyphy, it must be comparatively indifferent by which of his two methods these unusual Teneriffe landscapes are introduced into this book, though to readers in a future century it may make a great difference; for the photoglyph must last as long as the paper it is printed on, but the photograph may go the way of some of those beautiful specimens exhibited last year at the International Exhibition, and which faded before the eyes of the nations then assembled.”

The original photograph of this photoglyphic engraving of St Maurice was supplied to Talbot by the Parisian firm of Clouzard & Soulier. When Talbot first approached them, Charles Soulier responded admiringly: “We have no doubt that the new discovery of which you have told us equals those for which our art is already indebted to you & which have placed your name on the same level as Daguerre & Nièpce.” Every good story should end with a bit of mystery. There are a number of large Talbot photogravures dating from 1866 that exhibit a tonal range and uniformity that achieve a commercially viable level. The plates that were engraved, like this example, carry the enigmatic title of ‘Photo-sculpsit’ and I have never been able to determine much about this. Perhaps Photo-sculpsit got its start at Millburn Tower, for it was quite advanced by 1866, or maybe the work was continued at 13 Great Stuart Street in Edinburgh.

In 1877, the publisher for the English translation of Tissandier’s History and Handbook of Photography asked Talbot to contribute an appendix to balance out the French bias. Talbot split his manuscript into sections, the first dealing with his original invention of photography and the other explaining his work in photogravure. On 12 September 1877 Talbot wrote to the publisher apologising “I have not been well, which has delayed my sending you the rest of my paper – I now send the second part … the third part is in preparation & will complete the Appendix.” Tragically, he died within a week, the manuscript left unfinished. Talbot had already contributed two examples of Photo-sculpsit to include in each copy of the book, evidence that he had finally achieved his goal of rendering photographs in printers ink (those lucky enough to possess an original copy of this book have a good start on their Talbot photogravure collection). His son, Charles Henry, completed the manuscript as best he could. Lacking specific details, he recalled that his father had greatly improved the laying of the aquatint ground, but “there were occasional small explosions of the camphor vapour during the plate-warming.” Although Charles Henry was unsure that his father used the term Photo-sculpsit, the 1866 prints carry this title and probably relate to a project that Henry Talbot had conceived of as the conceptual successor to The Pencil of Nature. In 1866, he wrote to the French-born London engraver Ferdinand Joubert: “I have thoughts of publishing a small work illustrated by specimens of this invention – It may extend to eight or ten numbers, (three plates in each number) – they will not be retouched by hand in the smallest degree – I am aware that a skillful engraver might improve them, but my present object is, to show what can be done without any difficulty by the process itself. If I allowed them to be retouched (however little) the Public would be sure to attribute any merit the plates may have, to this subsequent manipulation.”

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Kim Trynor, Gogar Tram Depot, 2012. • Rosamond Talbot, Watercolours of Millburn Tower, 1861, from an album of 104 watercolours and pencil drawings by various family and other artists, probably assembled by Rosamond and spanning the period of 1856-1865. Fox Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT10346. • Rosamond Talbot to WHFT, 9/10 March 1861, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 08331. • WHFT, uncatalogued research notes from 1863, Talbot Collection, the National Media Museum, Bradford. • WHFT, Notré Dame de Pépine. Department de la Haute Marne, photoglyphic engraving, 1861, Hans P Kraus, Jr, New York. • Charles Piazzi Smyth, Astronomical Observations Made at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, vol. XII1, 1855-1859 (Edinburgh: Neill and Co., 1863). This is discussed in context in my “Piazzi Smyth at Teneriffe: Part 2, Photography and the Disciples of Constable and Harding,” History of Photography, v. 5 no. 1, January 1981, pp. 27-50. • WHFT, Church of St. Maurice at Vienne in France, Photo-Sculpsit, 12 July 1866; David A. Hanson Collection, Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Massachusetts, NE2698 T142c. • Charles Soulier to WHFT, 23 September 1858, Doc. no. 07032. His letter was in French: “Nous ne doutons pas que la nouvelle découverte dont vous nous parlez ne soit à la hauteur de celles que notre art vous doit déjà & qui ont placé votre nom sur la même ligne que ceux de Daguerre & de Niépce.” • Gaston Tissandier, A History and Handbook of Photography, rev. ed., edited by John Thomson (London: Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, 1878). • WHFT to Sampson Low & Co., 12 September 1877, Document no. 00839. • WHFT to Ferdinand Joubert, 29 August 1866, Doc. no. 09128. • A survey of WHFT’s development of photogravure can be found in my essay “ ‘The Caxton of Photography’: Talbot’s Etchings of Light,” in Mirjam Brusius et. al., William Henry Fox Talbot: Beyond Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 161-192.