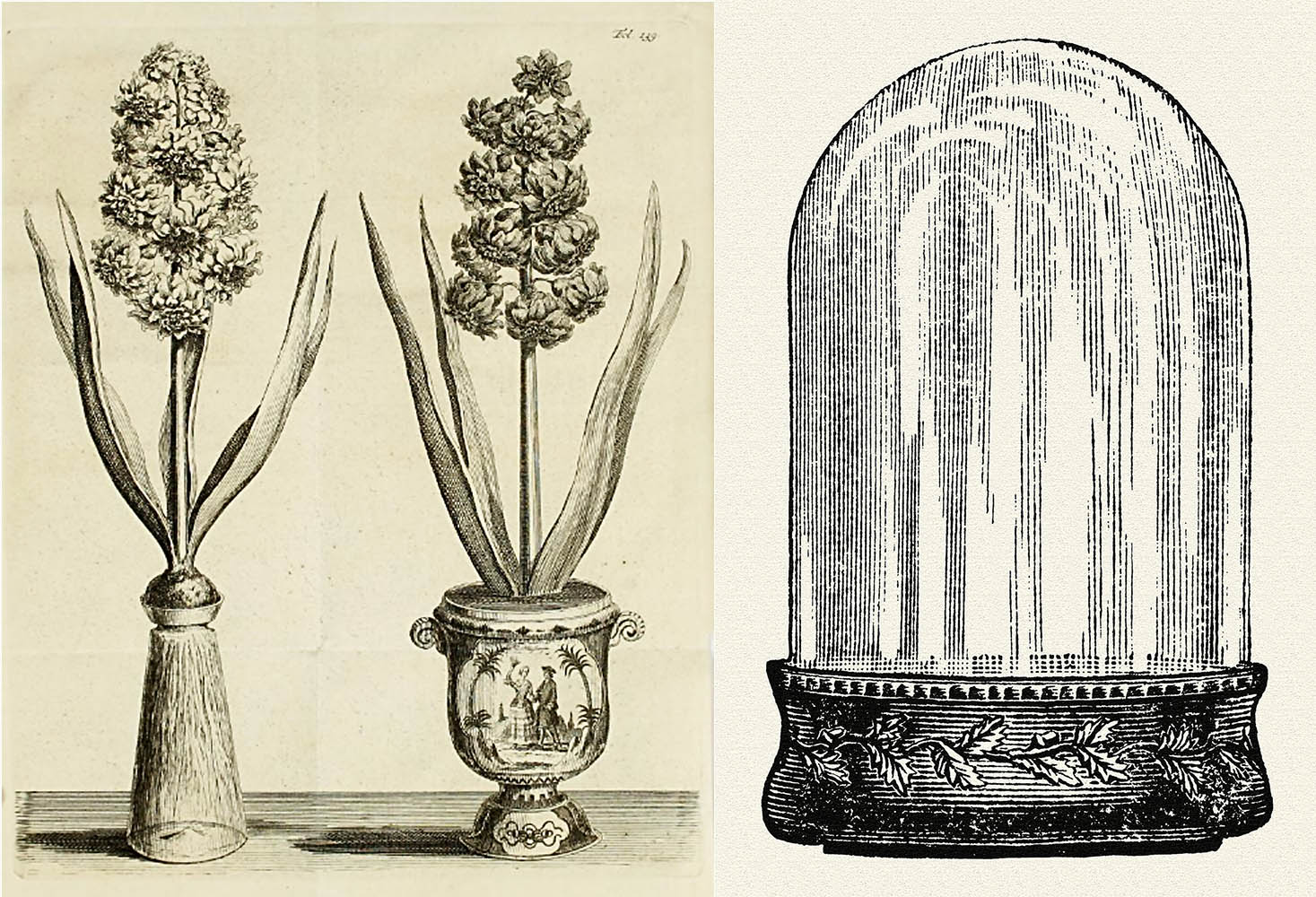

In last week’s post about Talbot’s window, I speculated that the objects on the sill were probably pen pots and the interior detail either a glass bell covering a scientific instrument or a chandelier lowered for cleaning. Professor William Becker of the American Museum of Photography immediately observed that yours truly was “obviously no indoor gardener. ” Fair enough. Plants droop when they see me coming, perhaps sensing the lack of a green thumb, surely not because they are threatened with a rendezvous with my kitchen cutting board. Bill goes on to observe that “those are plants placed to catch a few precious and rare rays of Wiltshire sunlight.” Another reader, John Winstone, architect and the son of the collector and historian Reece Winstone, said that “I’ll go for hyacinths under a Wardian case!”

And I may go for that as well for the shapes in the interior might well be hyacinths. The glass dome, often called a bell jar when used for vacuum experiments, was a common protective covering for scientific instruments or objects of curiosity. It could also be used to trap a moist draft-free environment for the benefit of plants forcibly resident indoors. These Wardian cases, or ferneries as they were often called, took a variety of forms – the above one had an terra cotta base, which helped to retain and regulate the humidity, much as the once-popular Romertopp clay roasters did for chickens.

Under extreme magnification sadly we learn little more, for the fibres of the paper began to dominate the image. Right now overcoming this seems to beyond the limits of Photoshop, but perhaps someday one of our readers, most likely a conservator, will write an app that will smooth the contours of the fibres and yield a clearer image. With what we have, the interior objects being hyacinths remains a believable option and perhaps the window sill items are indeed young plant shoots greeting the Wiltshire sun. Using photography to represent and illustrate plants was one of Talbot’s first interests, not surprising given his lifelong interest in botany and gardening. As early as 26 March 1839, during the first public quarter of photography, he wrote to his botanist friend William Jackson Hooker, asking “what do you think of undertaking a work in conjunction with me, on the plants of Britain, or any other plants, with photographic plates, 100 copies to be struck off, or whatever one may call it, taken off, the objects?” This first inking of The Pencil of Nature would have been a self-portrait of nature, displaying her vegetable world in a way that Talbot hoped would be both familiar and more detailed that conventional means of illustration. It seems like it should have been a natural pairing.

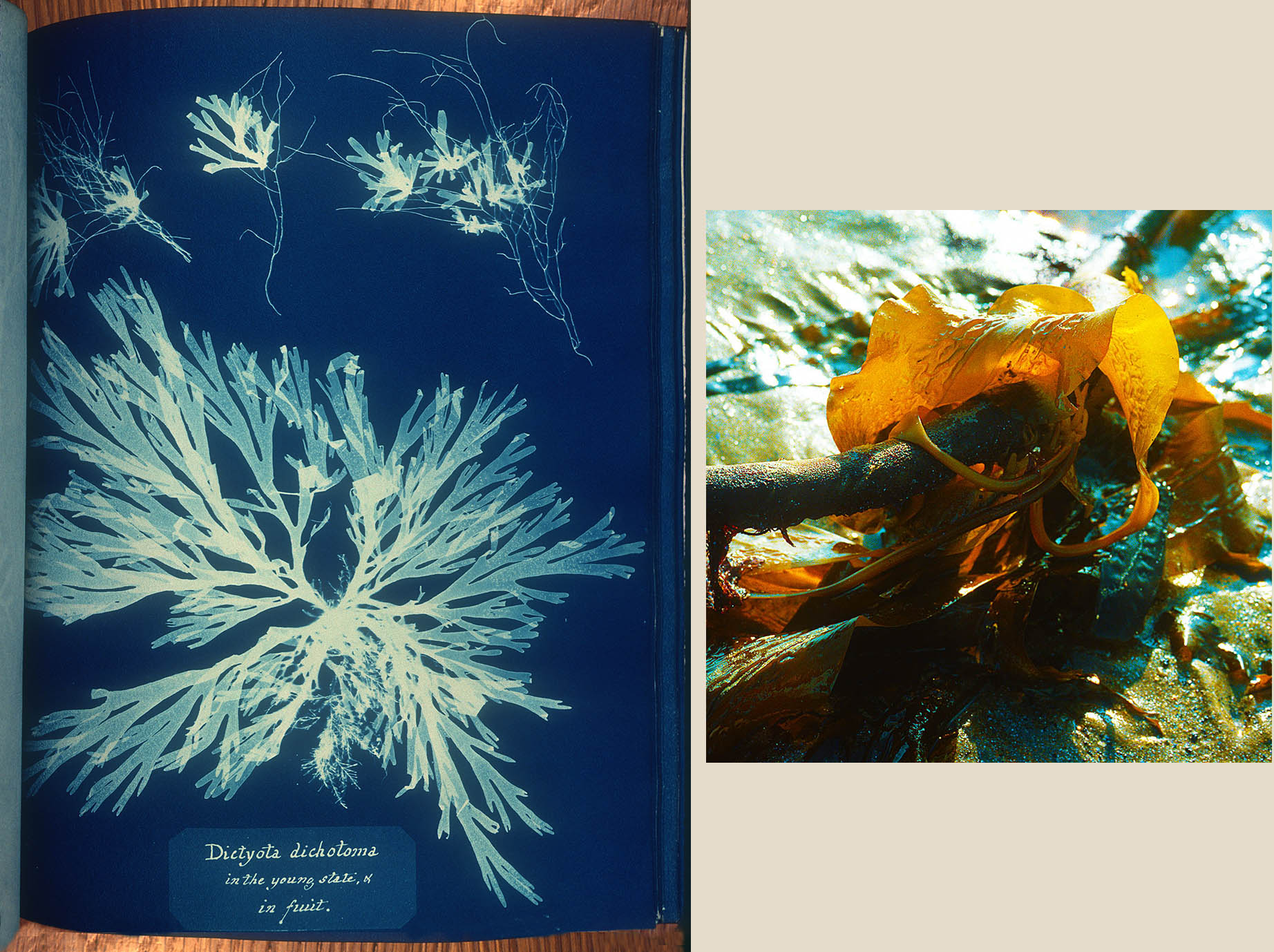

Not being a gardener, much less a botanist, I was puzzled in the early 1970s when I first started down the path trying to understand Anna Atkins’s cyanotypes. As I began to slowly piece together the bibliographic record of her book publication it seemed to me that it must have had an impact but I could find little trace of this in the literature. She was one of the first woman members of the Botanical Society of London. That combined with her closeness to her father, John George Children, brought her into contact with many influential botanists. As I began to meet more and more botanists during my quest, the reasons why photography failed to take hold in their field began to emerge. Talbot’s original term for photography – skiagraphy – carried some of the explanation. By necessity, the early photographs of plants were photograms, printed by contact and thus giving the view by transmitted light, not our normal way of seeing plants. Later, photographers were able to take photographs of plants in the camera by reflected light, such as Talbot’s own lovely Bush of Hydrangea in Flower, images which had a much higher degree of familiarity. Perhaps this was less of a concern for Atkins, for her ‘flowers of the sea’ were depicted against the cyanotype’s naturally blue background, much as they might have been seen by a diver if facing towards the skykight. Another big problem of photographic illustration of plants was that botanists were used to engravings that typically had one or more detail drawings in addition to the main one. Atkins emulated this in some of her plates by arranging more than one specimen on a sheet but this still did not allow for magnification. Another major drawback of photography for botanical illustration was the flip side of its very strength. Photography excelled at depicting a real-world object very precisely. However, botanists consulting an illustration wanted to observe what was typical for a type of plant, not what was specific to an individual specimen. In the end, this lack of ability to generalise the image was perhaps the single largest drawback of botanical photography.

Still, the ready availability of plant specimens continued to capture Henry Talbot’s imagination and he returned to produce a substantial number of photograms even after his invention of the calotype. He sent this particular arrangement of six leaves in 1842 to his German colleague, the botanist Dr Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius. Did Martius know what these were? Can you identify any of these leaves? That will be a question asked frequently when we begin posting the images in the Catalogue Raisonné.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, The Window of Talbot’s Library at Lacock Abbey (detail), salt print from a calotype negative, 25 January 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA2114, Schaaf 2551. • Hyacynths from George Voorhelm, Traité sur la Jacinte (Haarlem: N. Beets, 1773), Getty Research Institute; wardian case from Julius J. Heinrich, The Window Flower Garden (New York, NY: Orange Judd Company, 1880), p 46. • WHFT to William Jackson Hooker, 26 March 1839. Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, EL13.141; Talbot Correspondence Document no 03845. • Anna Atkins, ‘Dictyota dichtoma, in the young state & in fruit,’ British Algæ, Cyanotype Impressions (Sevenoaks: privately published, 1843-1853), The Linnean Society, London. • Some readers will be familiar with my 1985 Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins – this built on my earlier publication, “The First Photographically Printed and Illustrated Book,” The Papers of the Bibliographic Society of America, Second Quarter, 1979, v. 73, pp. 209-224. • WHFT, Arrangment of Six Leaves, salt print from a photogenic drawing negative (WHFT included this in a 10 June 1842 letter to Martius – see Doc. no. 04530); the Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Munich, v. 58 no. 133, Schaaf 3676. • WHFT’s relationship with botany is considered in Anne Secord, “Talbot’s First Lens: Botanical Vision as an Exact Science,” in Mirjam Brusius, William Henry Fox Talbot: Beyond Photography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 41-66.