Publishing on April Fools Day is always risky business. Personally lacking a sense of humour, of course I wouldn’t dream of winding you up on a day like this. The following is not a joke. Really. Trust me.

April Fools Day fell on a Thursday in 1841. The day before, Lady Elisabeth and Henry returned to Lacock from London, taking advantage of the recently-opened railway line (his mother did not have the fear of this new mode of transportation that haunted his wife Constance). On 1 April Lady Elisabeth recorded in her diary that it was a ‘rainy’ day’, amplified by Talbot’s inscription on the photograph he tried that day of ‘very dark weather.’ One can only think that he was intentionally testing the limits of his new calotype negative process. I’m not quite sure what he came up with here, perhaps the silhouette of the Abbey’s roofline? In any case, this was the opening of a burst of creative testing.

One of the first places to check when examining Talbot’s photographs is within his research notebooks, especially P and Q which cover the early years of photography. They are wonderfully diverse and maddeningly incomplete, reflective of Henry’s active imagination. Photographic thoughts are mixed with records of experiments, all of which is stirred into a broad context of other activities. This is page 67 from his Notebook Q, carrying over thoughts about magnetism from 5 March 1841 and continuing with his photographic experiments right after April Fool’s Day.

Rod with two knobs K, K´ the magnetism pulls the lever down acting on K´; the springs push it up, acting on K. Brass may be gilt by washing it with chloride gold mixed with carbazotic acid in alcohol, benzoic acid in alcohol.

2 April. Paper washed with bichromate potash, is sensitive to light. Image of leaf, etc. is bright yellow upon brown. Washing with water fixes it, the yellow being washed out, the brown only partially so. These facts discovered by .

I find that the green deoxidised chromate washed on paper is not sensitive. In the present instance the proportions were about

2 strong sulphuric acid

5 alcohol

5 bichromate potash

A washed chrome photograph may be washed with muriate tin and heated, to try and blacken the paper and obtain a positive picture.

Moonlight (not concentrated) makes an image of a fern leaf etc. on calotype paper in about half an hour.

Gallo-gold (or solution of gold + g) gilds German silver.

“Gilding metal” (copper + a little tin?) may be first slightly silvered, and then takes gilding better.

To silver “gilding metal” _ nitrate silver + g. in alcohol + six to twenty parts of water, silvers it instantly if dipped in.

The ‘gilding metal’ was to become part of one of Talbot’s patents. The name that he could not recall was that of the eccentric and intriguing Scot, Mungo Ponton. Some of our readers will have made gum bichromate prints (dichromate to the newer generations) which are one of the many derivatives of that discovery.

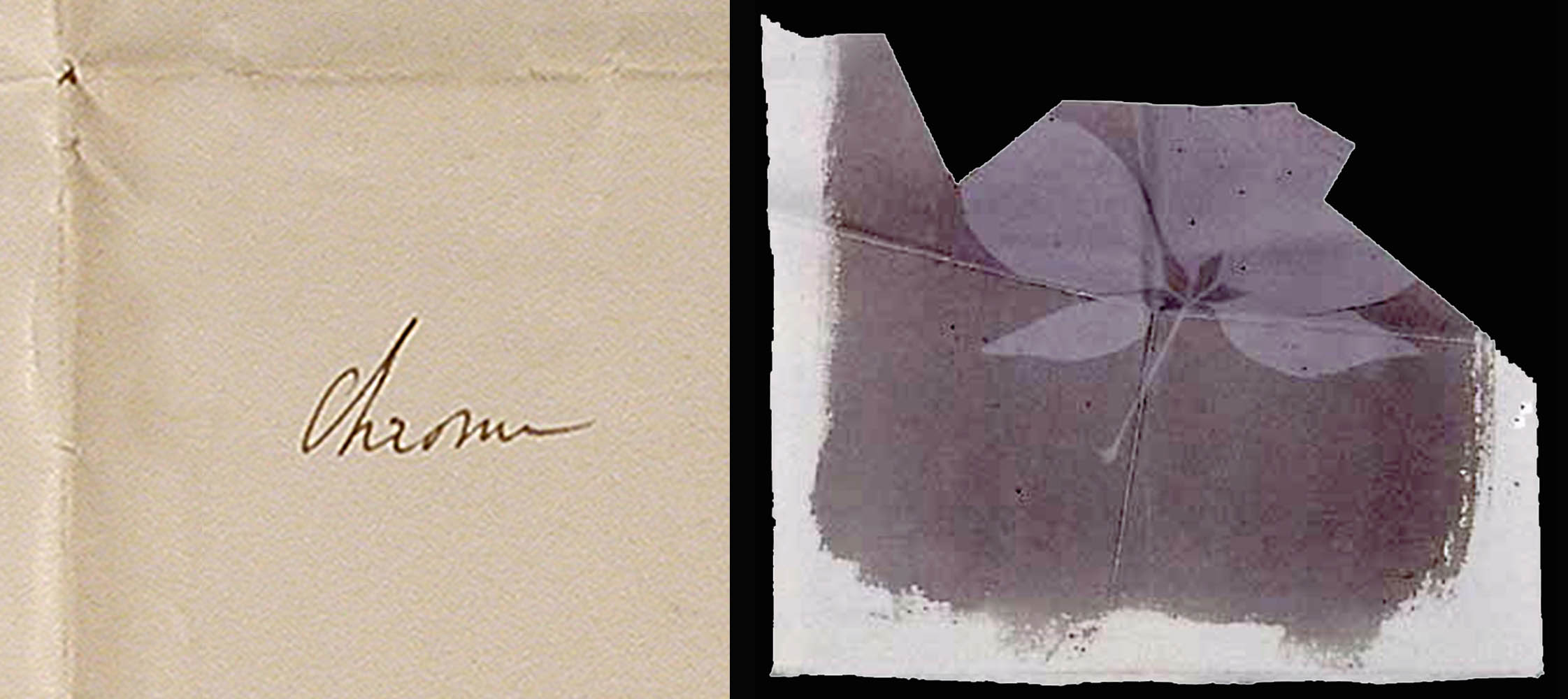

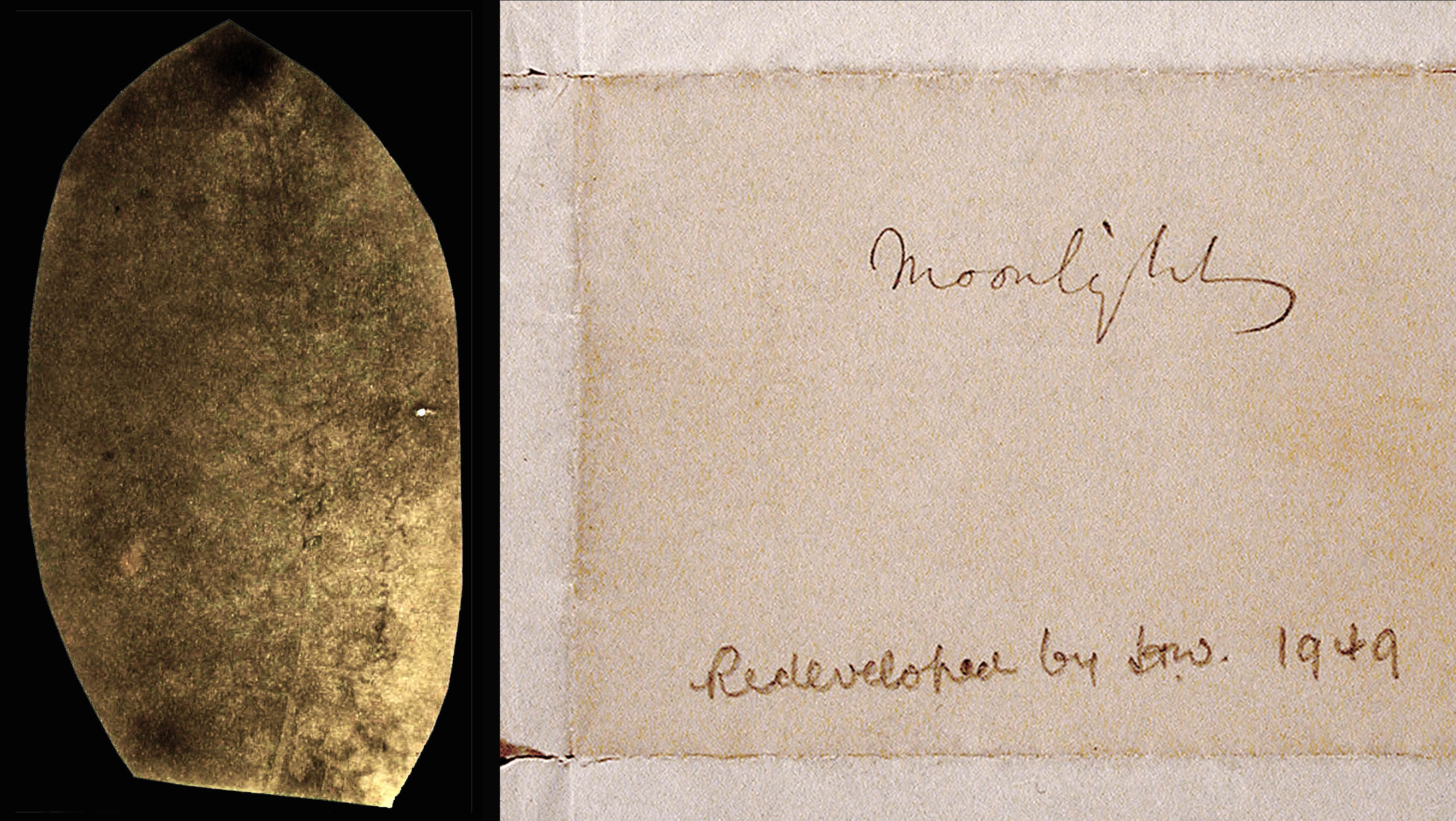

Three examples of these 2 April bichromate experiments are known to have survived, still preserved in the folded wrapper Talbot labeled as ‘Chrome.’ Was this negative nibbled away by Talbot himself for some reason? A more likely explanation of its losses is that a subsequent researcher took off little bits for chemical or radiological testing.

Of perhaps greater interest is the intriguing reference to using moonlight to make an image on calotype paper with a half hour exposure. This wasn’t the first time that Talbot had tried to harness moonlight. On 15 November 1839, he wrote to his friend Sir John Herschel, explaining that “I have continued at intervals my photographic experiments. I took advantage of the bright full moon in September to try the effect of the lunar rays upon my paper, and I obtained a distinct impression in 10 minutes, by help of a condensing lens, altho’ the rays passed through 2 plates of glass besides the lens itself. The same paper is sensitive to lamplight. I think this paper, or some modification of it, will prove very useful for the Camera Obscura.” The full moon that September fell on the 23rd, but so far I have not identified any surviving images from that date.

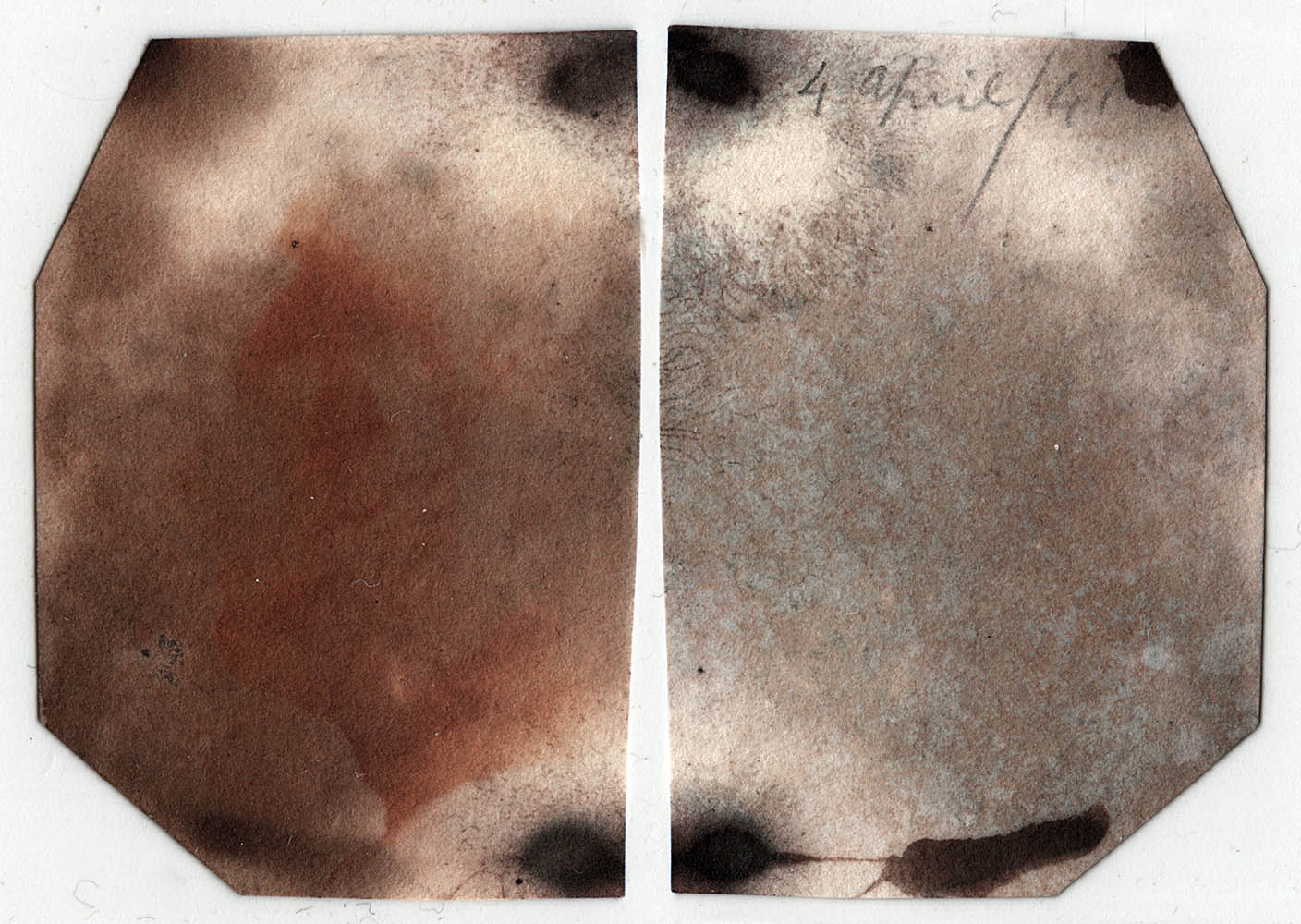

There are two extant photographs from the April 1841 moonlight experiments, dated in his hand on the verso and again preserved in one of his labeled wrappers. However, the later inscription on this wrapper makes it clear that we cannot judge how successful these were initially. Harold White helpfully recorded that he had redeveloped them in 1949; whether the original images were merely weak or were totally obscured by then we will never know. What is clear in the barely-visible fern is that the calotype paper responded usefully to the moonlight. Within days of accomplishing this Talbot sent examples to his friend Sir David Brewster and the Scottish scientist responded on 5 May: “The sensitiveness of the Calotype Paper to Moonlight is a most extraordinary fact, and cannot fail to excite great interest as a scientific fact. That the chemical rays shd shew themselves by such marked effects, & with out condensation, while the heating rays cannot be rendered effective by the most powerful Lens & Specula is truly wonderful.” His amazement mirrored the controversy over the very nature and origin of moonlight at the time.

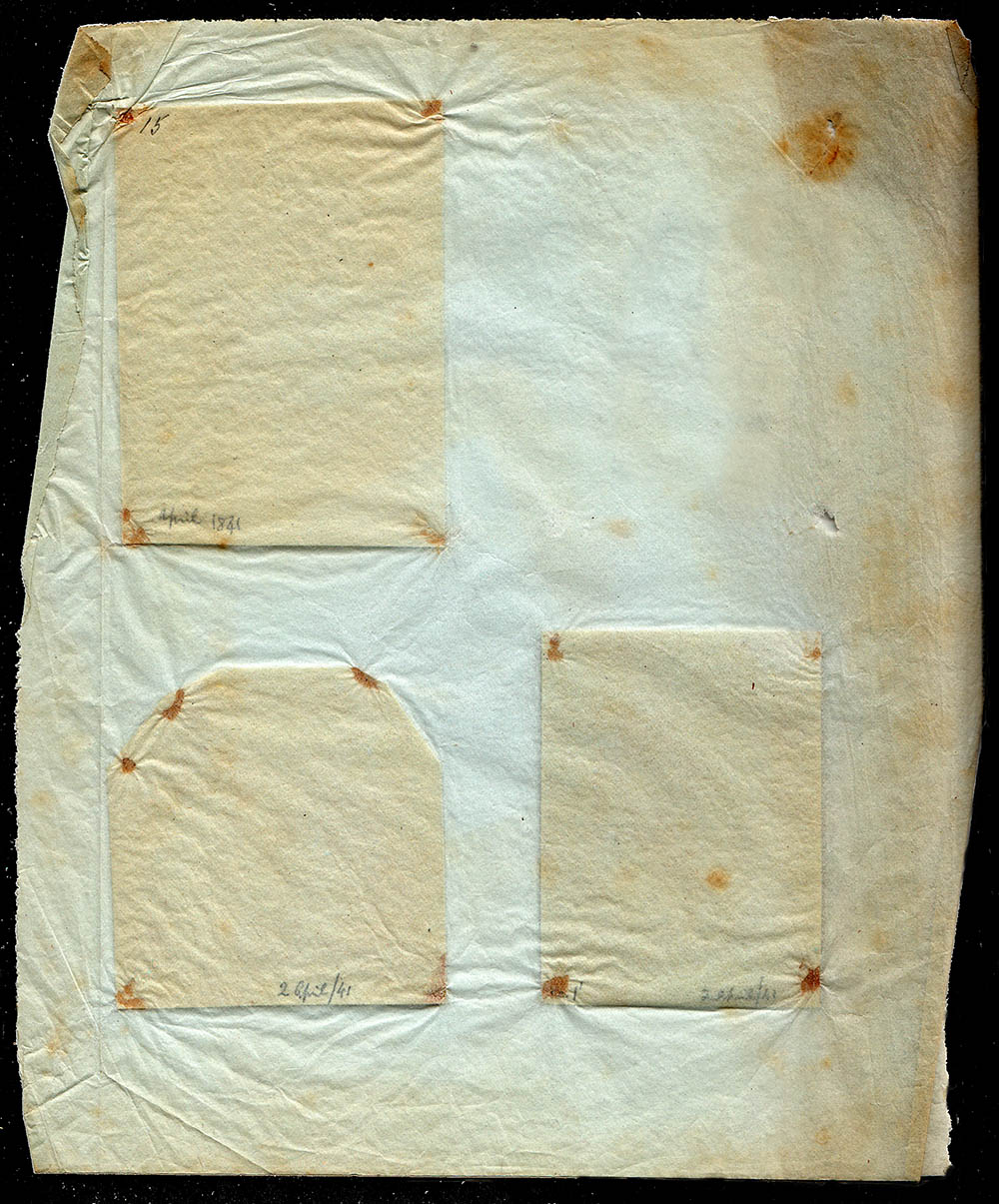

Talbot was very active photographically in the period following the rainy April Fools Day. Above is the reverse side of a sheet of tissue paper on which he has mounted three calotype negatives of statuary, the thin paper allowing his inscriptions to show through. This rare, although not unique, survivor was given by the family to Eugene Ostroff, the Curator of Photography at the Smithsonian Institution, in order to encourage his active testing of Talbot originals. We have no way of knowing how many sheets of experiments like this that Talbot created, nor has any record been found so far of what their significance was to him. They may have merely been a convenient way to bundle related items together, a more formal and permanent method than those folded into labeled sheets.

When I saw these tissues for the first time, I realised that they called into question a long-held assumption. The verso of many of Talbot’s photographs have either residues of glue in the corners or stains that indicate that they were once there. In the case of camera negatives, as the above one of Patroclus, I had assumed that this was evidence of his practice of temporarily gluing the sensitive paper to the back of his primitive homemade ‘mousetrap’ cameras. Where prints have a residue, I had always assumed that they had been removed from album pages, a sad practice that I know happened all too often after Talbot’s death. Indeed, sometimes there are paper fibres left behind that match Talbot’s typical album pages. But perhaps some of these were once similarly mounted on tissues as part of a related group of experiments?

While many of these small negatives were clearly meant to be experimental and were probably never printed, there are companion ones from this period that Talbot saw as being interesting photographs. Here is a lovely little Patroclus, still mounted on a page in one of Talbot’s original albums. The dating that he applied in pencil on the verso of the negative clearly shows through in the print.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, experimental paper negative, 1 April 1841, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995-206.225; Schaaf 2571. • WHFT’s notebooks P and Q are in the National Media Museum, Bradford; their pages are reproduced in full facsimile and transcription in my Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). • WHFT’s 1842 patent was No. 9528, Improvements in Coating or Covering Metals with other Metals. • Mungo Ponton (1801-1880) was the Foreign Secretary for the Society of Arts for Scotland. His bichromate method was not suitable for use in the camera, but it became the critical foundation for many significant later methods, including WHFT’s own work in photogravure. His “Notice of a cheap and simple method of preparing paper for Photographic Drawing, in which the use of any salt of silver is dispensed with,” was read before the Society on 29 May 1839 and published in the Transactions of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts, v. 1, pp. 336-338. • WHFT, Leaves, bichromate process, 2 April 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London; Schaaf 4331. • WHFT to Sir John Herschel, 15 November 1839, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 3971. • WHFT, Fern by Moonlight, calotype negative, 2 April 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London; Schaaf 2572. • Harold White’s experiments with intensifying and re-developing WHFT’s originals were often successful – see the examples in my Sun Pictures Catalogue Three: The Harold White Collection of Works by William Henry Fox Talbot (New York: Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc., 1987 ). • Sir David Brewster to WHFT, 5 May 1841, Doc. no.. 4252. • WHFT, Bust of Patroclus, calotype negative, 4 April 1841, recto and verso, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995-206.132; Schaaf 2580. • WHFT, Bust of Patroclus, salt print from a calotype negative, 4 April 1841, Talbot Collection, the National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-368/19; Schaaf 1116. • My thanks to Roger Watson, Curator of the Fox Talbot Museum at Lacock, for locating the elusive digital images of the wrappers.