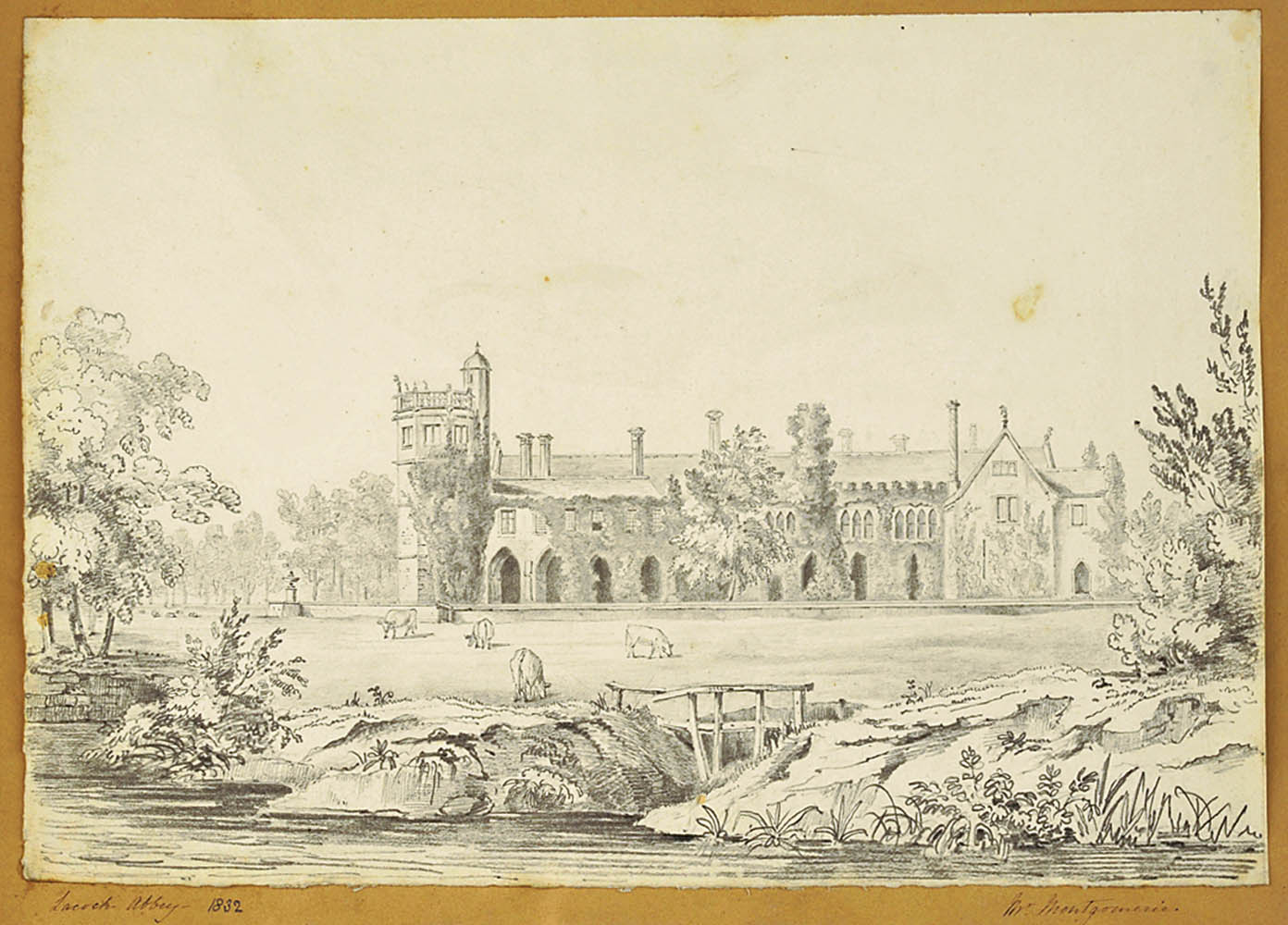

Viewed from the River Avon, Lacock Abbey is instantly recognizable from the Rev George Montgomerie’s detailed 1832 pencil drawing. Montgomerie was a close friend of all the Talbot family but particularly so of Lady Elisabeth and this is one of dozens of his drawings and watercolours contained in a number of the Talbot family’s albums. The year after he examined this drawing, Henry Talbot would be on the shores of Lake Como, being faced down by the intimidating camera lucida and thereby inspired to invent photography. If he could have drawn as well as Montgomerie there would have been little reason for the new art to even have occured to Talbot.

Talbot probably took this photogenic drawing ‘mousetrap’ negative during the glorious summer of 1835, three years after Montgomerie’s drawing. It is exciting but crude, promising but only indicative. At some point in its life, it was hinged from the bottom, most likely not by Talbot himself, but perhaps early in the 20th century by someone displaying it either at Lacock Abbey or perhaps at the Royal Photographic Society. In 1934 it was donated to the Science Museum by Miss Matilda Talbot. They might have applied this tape, which unless one of my conservator friends speaks to the contrary, I’m going to guess is the black binding tape commonly employed for glass lantern slides. By 1934, this was less commonly used. Before then, collections were freely shared between the Royal Photographic Society, the Science Museum and Lacock Abbey, so its travels and encounters are uncertain. Why is it mounted upside down? Is the explanation simply that amongst a group of photographers, such as the members of the RPS, the logical decision was made to display the negative as it would be seen in the camera, image inverted? In order to spare you the exercise of standing on your head, I’ve inverted it back on the right – one can clearly make out the distinctive Sharingtons Tower that anchors the southeast corner of Lacock Abbey.

What factors led to Talbot being able to produce an image like Lacock Abbey Reflected in the Avon just a few years later? What propelled his steady artistic advance? One answer lies within the man himself. When Talbot invented his first photographic process, naturally there was no thought of developers – no thought of a magic elixir that would make an invisible image come to life. Instead there was the expectation that Nature would be able to draw her own picture. And she did. His photogenic drawing process was a print-out process, where solar energy alone reduced the silver salts to a visible silver image. When the negative paper was removed from the camera the image was at full strength, only awaiting the fixing process to make it permanent. Talbot was able to immediately compare the scene in front of his camera with the negative that nature drew – he learned from his own art. Had he discovered the calotype first, with the revealing of the image delayed by a trip to the darkroom, remote from the original subject, I feel that he would not have learned as quickly

Surely another major factor in Talbot’s artistic evolution was the criticism and advice that he received from family and friends. Although a miserable failure as an artist himself, Talbot was surrounded by ladies of his household who were quite accomplished with pen, pencil and watercolour. And there were many family friends who were artists in their own right. George Montgomerie was one of these.

Born in 1790, George was the younger brother of Thomas Molineux Montgomerie, of Garboldisham in Norfolk. Being second in line, George took the typical path towards the clergy, becoming the vicar of the local St. John the Baptist church. One luxury of being a clergyman was that he had an unusual amount of freedom with his time and the ability to travel, something denied to most of his economic strata, common folk who lived and worked by the light of the sun. Surely that is why a disproportionate number of early photographers wore the collar.

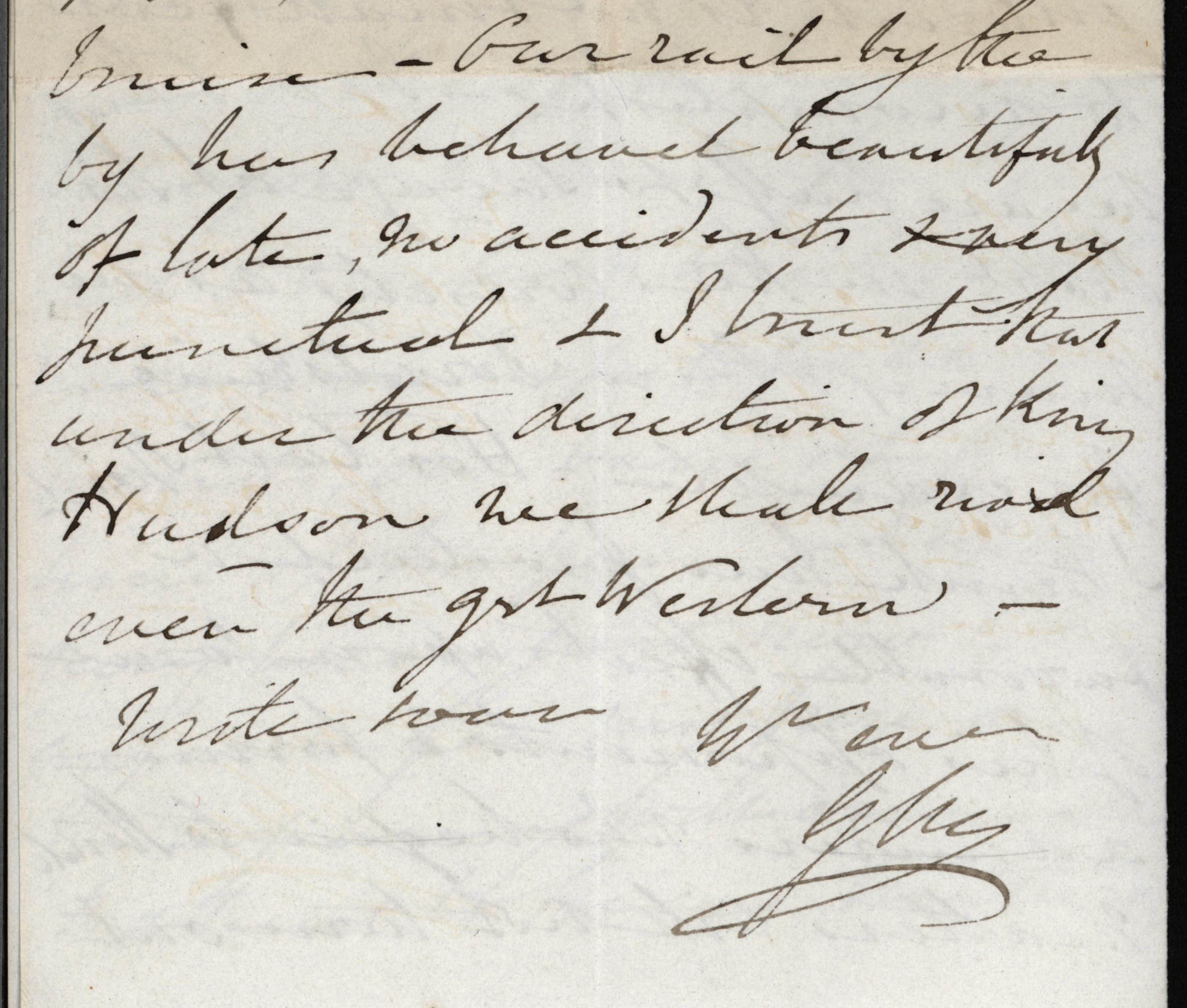

At least by the early 1820s George is mentioned with frequency in the Talbot family’s personal correspondence. He visited Lacock Abbey and often met up with the Talbots and the Feildings in London or in their foreign travels. He also had an interest in the rapidly emerging railway system, a topic of particular interest to Henry Talbot.

Constance was terribly worried about railway accidents, Henry less so, but this letter also reveals something of the economic aspects of the new technology. George ‘Railway King’ Hudson ruthlessly developed railway expansion into Norfolk, forcing competitors to sell out to him and amassing a great fortune, eventually falling into disrepute.

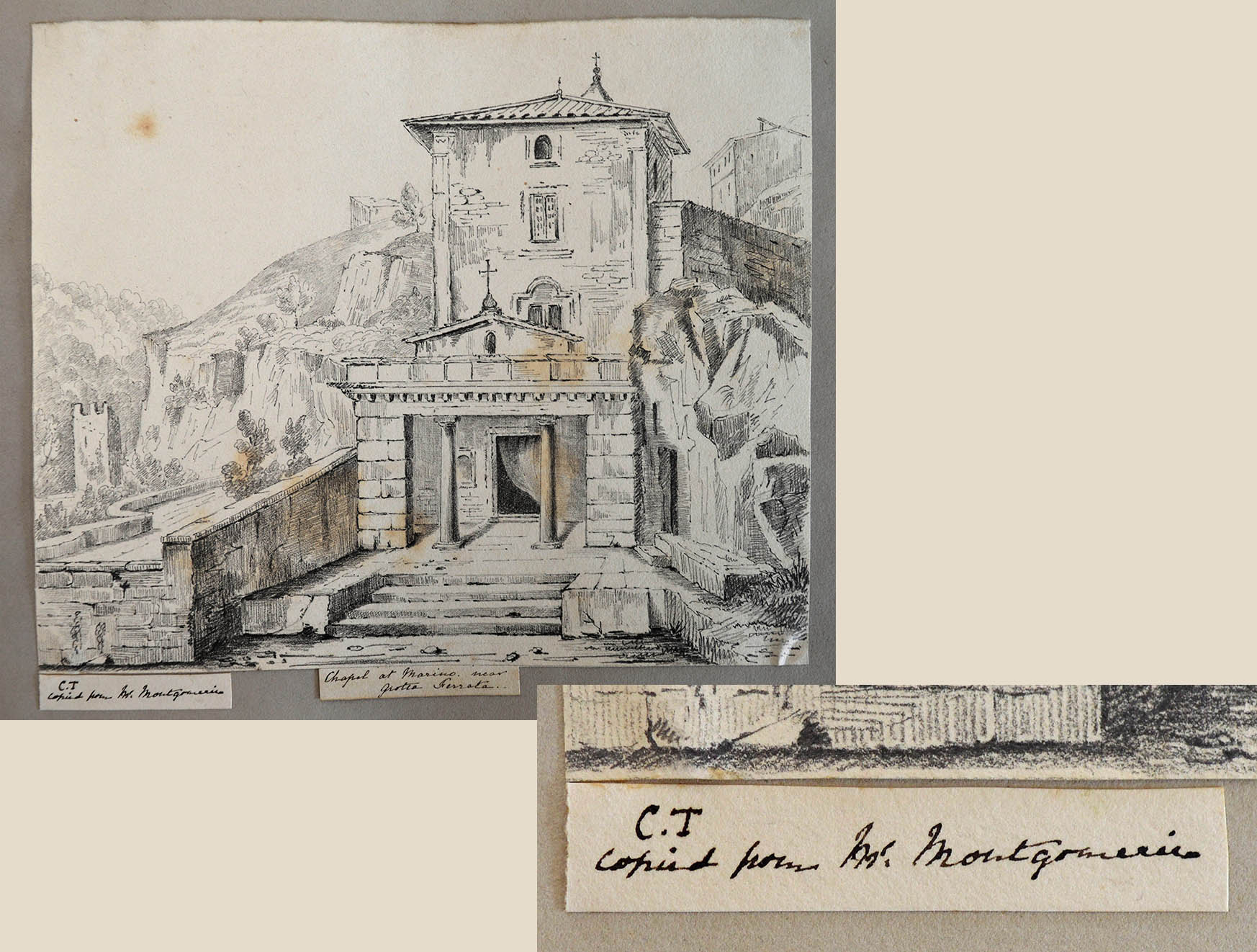

In spite of her skepticism of the rails, Montgomerie embraced Constance Mundy when she married Henry, taking an interest in her artistic development.

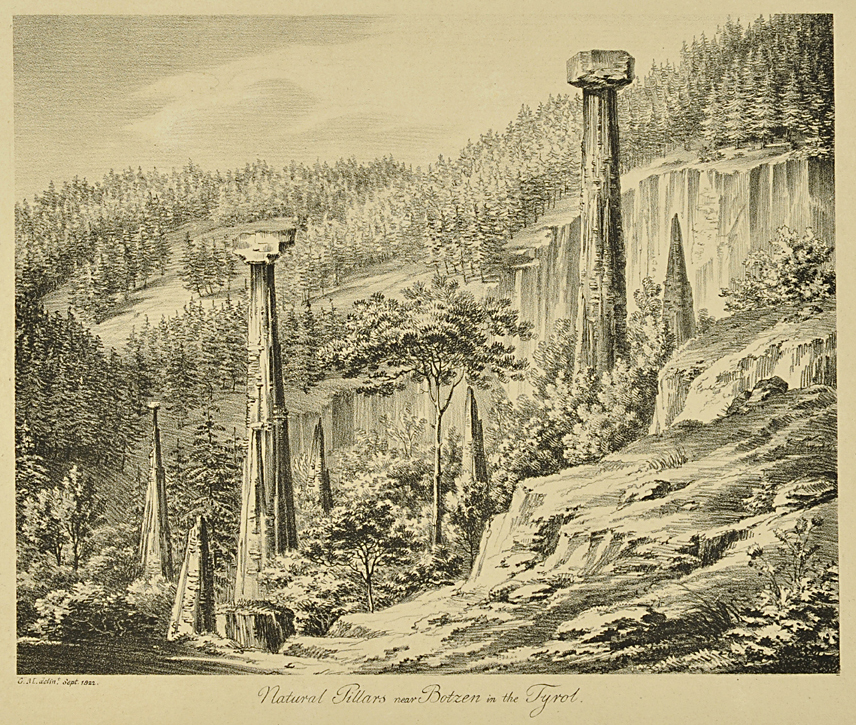

Copying the work of a senior artist was a common way to learn. By 1824, Montgomerie was expanding into new artistic endeavours, making lithographs of his own drawings.

George Montgomerie, Natural Pillars near Botzen in the Tyrol, lithograph, September 1822

Lady Elisabeth became enamored of the art of lithography as well, and although the documentary evidence is slender, the lithographs that she made in the period after this bear a striking resemblance to her friend Montgomerie’s style.

But there was a melancholy side to George Montgomerie and if one studies Talbot’s 1843 portrait of his friend this becomes apparent. I think this might be one of Talbot’s most perceptive portraits, capturing the complex character of this creative but tortured soul. The low camera angle adds a monumentality to the person – is the head slightly turning away an act of defiance or one of avoidance? Made more dynamic by a low camera angle, the portrait presents a dramatic interpretation of a tortured and creative soul. Amongst themselves, letters between members of the Talbot family expressed frequent, if coded, concerns about Montgomerie’s state of mind. Their fears were well grounded, for on 17 January 1850 George Montgomerie took his own razor to his throat in his rectory at Garboldisham, dying instantly. As was typical for suicides, much of the historical record about him was destroyed, along with most of his artwork. I wish we knew more about him. Because of the unusual range and quantity of the Talbot correspondence that is preserved worldwide, it is often the main or even the only record of a particular person’s life. Such is the case with George Montgomerie.

Talbot took at least two portraits of his friend in the session on 13 April 1843 . Prints are not known to have survived for either of these negatives (perhaps destroyed because of the circumstances of Montgomerie’s death) so I have taken the liberty of making virtual prints of them. This second negative, less powerful as a portrait, still makes a valuable contribution because Talbot dated it on verso.

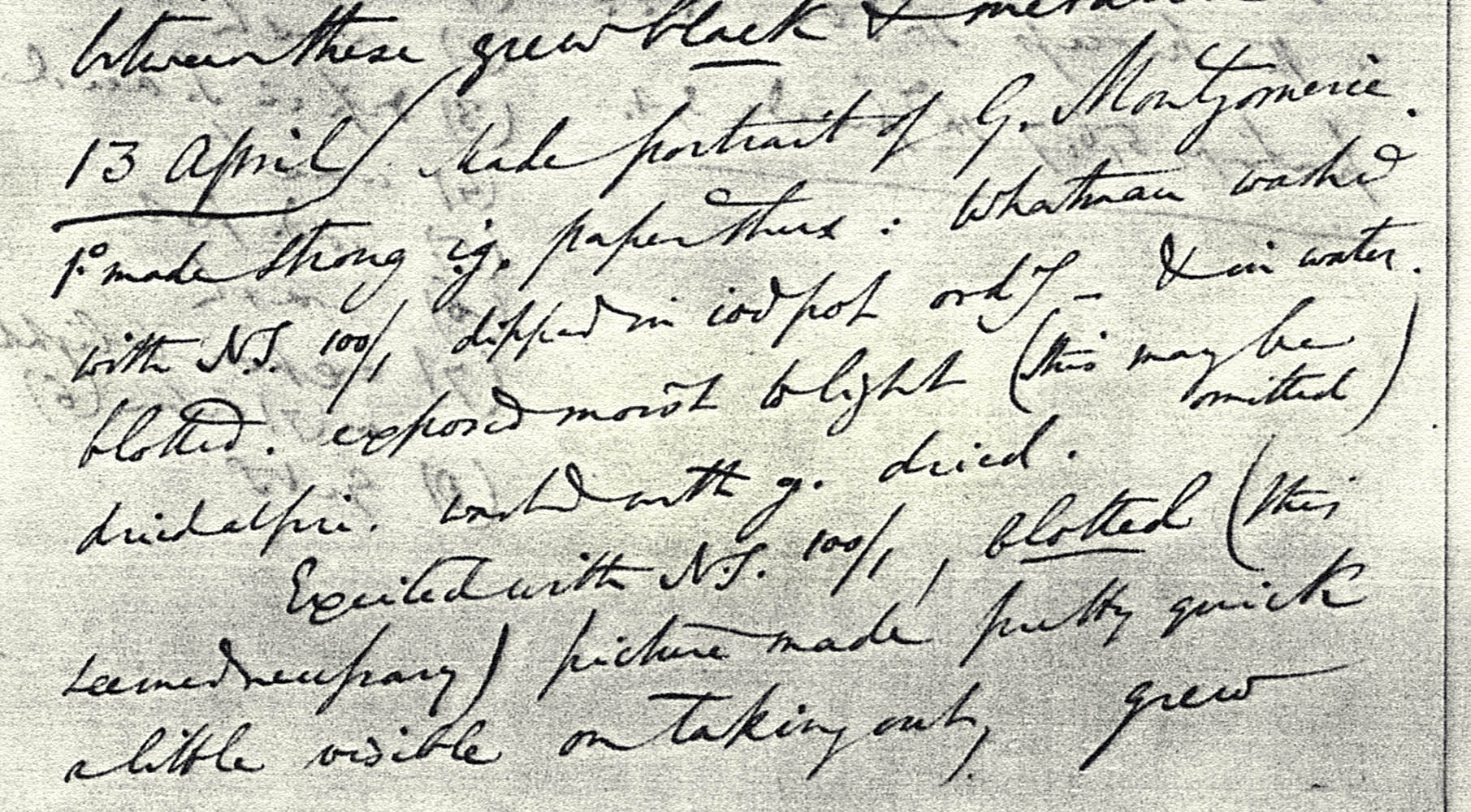

That date gives us a gateway into Talbot’s research notes. In addition to capturing the character of his friend, Talbot used his face for experimentation; in fact, that may have been how the session started. He made an unusually strongly iodised paper, finding it necessary to blot the chemicals. ‘Exciting’ it – sensitising it – with a silver nitrate solution, he found his exposure time to be quite short. As was sometimes the case, a faint image appeared on exposure, growing quickly in strength as the gallic acid developer worked its magic.

I would like to think that Talbot dated this negative as a reminder of his experiment, leaving the companion one undated because he knew that it was a timeless representation of the family friend, Geroge Montgomerie. The first one he simply labelled ‘G.M.’.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Many thanks to Matthew Neely, who is currently cataloguing the Talbot Personal Archive for the Bodleian Libraries. • George Montgomerie, Lacock Abbey, pencil drawing, 1832, Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT10343.1. • WHFT, Lacock Abbey, photogenic drawing negative, likely summer 1835, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1419, Schaaf 1086. • WHFT, Lacock Abbey Reflected in the River Avon, salt print from a calotype negative, before May 1845, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1255/1, Schaaf 74. This is an unusually difficult negative to date; it was published in The Pencil of Nature as plate XV in May 1845. • WHFT, George Montgomerie, calotype negative and virtual print, 13 April 1843, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York, Schaaf 1555. • George Montgomerie to Lady Elisabeth Feilding, 23 February 1846, Talbot Archive, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT10962. • Constance Talbot, after George Montgomerie, Chapel at Marino, near Grotta Ferrata, ink over pencil, in her personal album of drawings and photographs, Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT10338.21. • George Montgomerie, Natural Pillars near Botzen in the Tyrol, lithograph, September 1822, Talbot Archives, the Bodleian Libraries, Oxford, FT11241. • WHFT, George Montgomerie, calotype negative and virtual print, 13 April 1843, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-3749, Schaaf 2716. • WHFT, Research Notes, April 1843, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA43-46.