Guest post by Brian Liddy

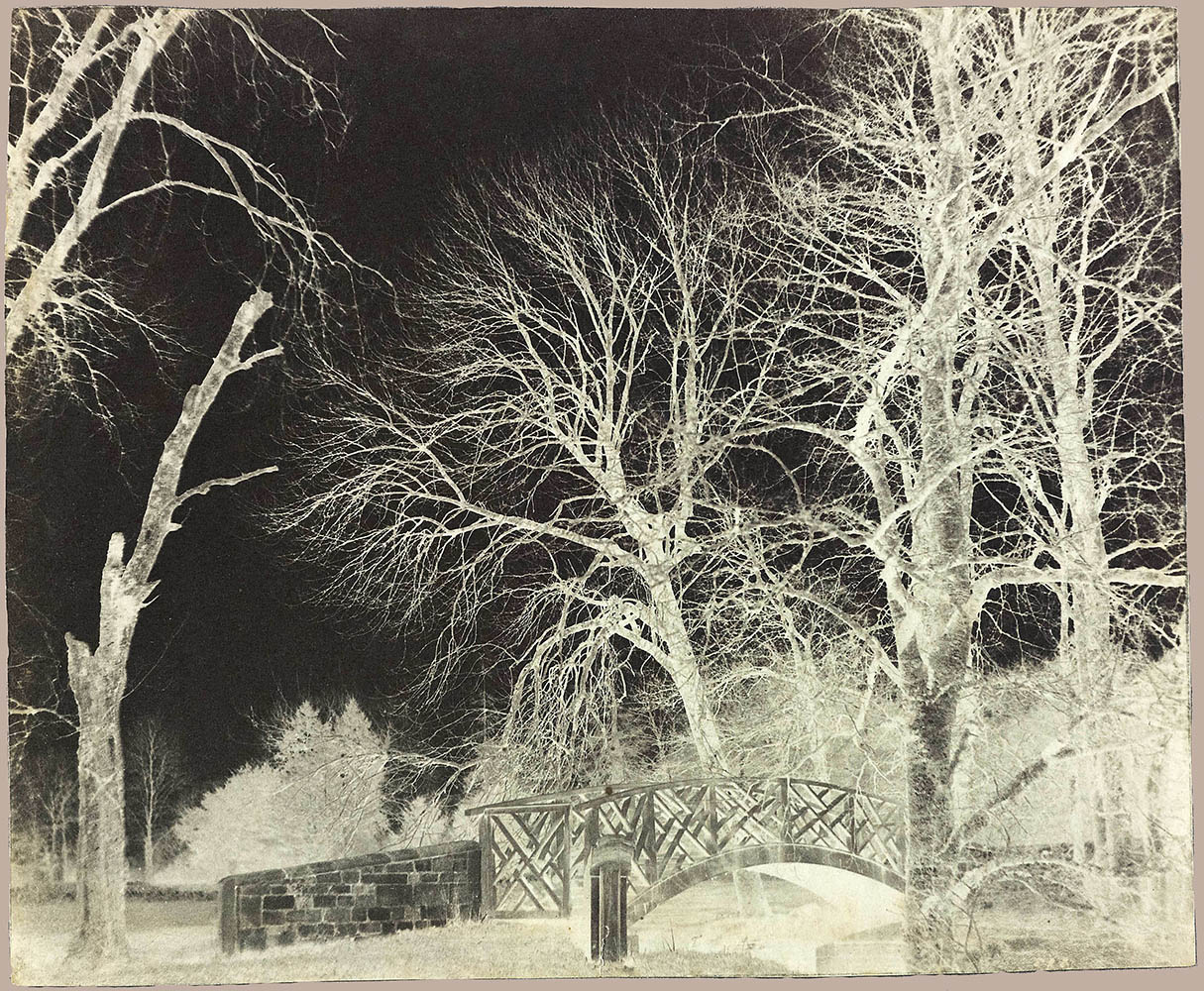

A photograph represents a moment in time, frozen. For some of Talbot’s photographs we know exactly when he took them, sometimes right down to the day. For others, our guesswork is guided by clues such as the photographic process and whatever has been recorded within the image. Often the season is easily established, with leafless trees clearly signifying winter.

To me, viewing this landscape as a negative is evocative of this time of year. The stark trees rendered in white against a dark sky could pass for a snow scene. The irony here is that in reality there had to be good strong light for this photograph to be taken. Perhaps it was the kind of winter’s day I like – bitterly cold but with blue skies and sunshine. The kind of rare winter’s day which would have tempted Talbot to brave the cold for the time-consuming process of setting up his camera on the grounds of Lacock Abbey. Photography then was far from instantaneous, so any wind in the trees during the exposure would have confused the sharp outlines of the twigs and branches. The central ones are rendered perfectly clearly, marking a windless day. The fact that those branches towards the edge of the photograph are less distinct results from his lens, not meteorology.

The China Bridge, as it was sometimes known, is no longer there, its only testimony being the stones that once anchored it to the riverbank as the river Avon persisted on its journey through Talbot’s estate towards Bath and Bristol. The presence of a bridge with a latticed Chinese design in an English country estate can be explained by the 18th c. European fashion for what was understood to be Chinese at the time. Influencing everything from the decorative arts to architecture and landscape gardening, the style came to be known as Chinoiserie. It survives to this day in the form of the familiar Willow Pattern dinnerware, popularized in Britain by the end of the 18th c. The romantic fable associated with the pattern tells the tale of two lovers, Koong-se and Chang, eloping. In the story they were chased over a bridge just like the one in our photograph. It ends with the dramatic deaths of the lovers (but at least they were transformed into doves by the gods).

Before I get too distracted by Chinoiserie and ill-fated lovers let me return to the vital role of the bridge in this composition. Its function is two-fold. Firstly, as a simple visual device the bridge leads your eye into the scene. Its regular geometric design also contrasts nicely with the random patterns created by the branches of the leafless trees nearby. Secondly, the bridge is symbolic. We cross a bridge from one riverbank to the next, just as we have just crossed from the old year to the new year. At the risk of reading too much into the photograph, note the one dead tree standing in isolation to the left on our side of the river. The path on the far side is obscured by the thicket of trees there. It remains unclear where we are heading. Like the year ahead, who knows what’s in store for us?

Crossing the bridge hopefully and with all good hopes and wishes for 2017,

Brian Liddy

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Lattice bridge over the River Avon at Lacock – winter trees, calotype negative, undated, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2068; Schaaf 1161. Two extant prints from this negative are known: the British Library (LA289) and the George Eastman Museum (81:2850:01). A variant view of this bridge was dated by Talbot to 21 February 1841 but it appears to be the earlier of the two. It is illustrated in Larry J Schaaf, The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), plate 39; Schaaf 2553.