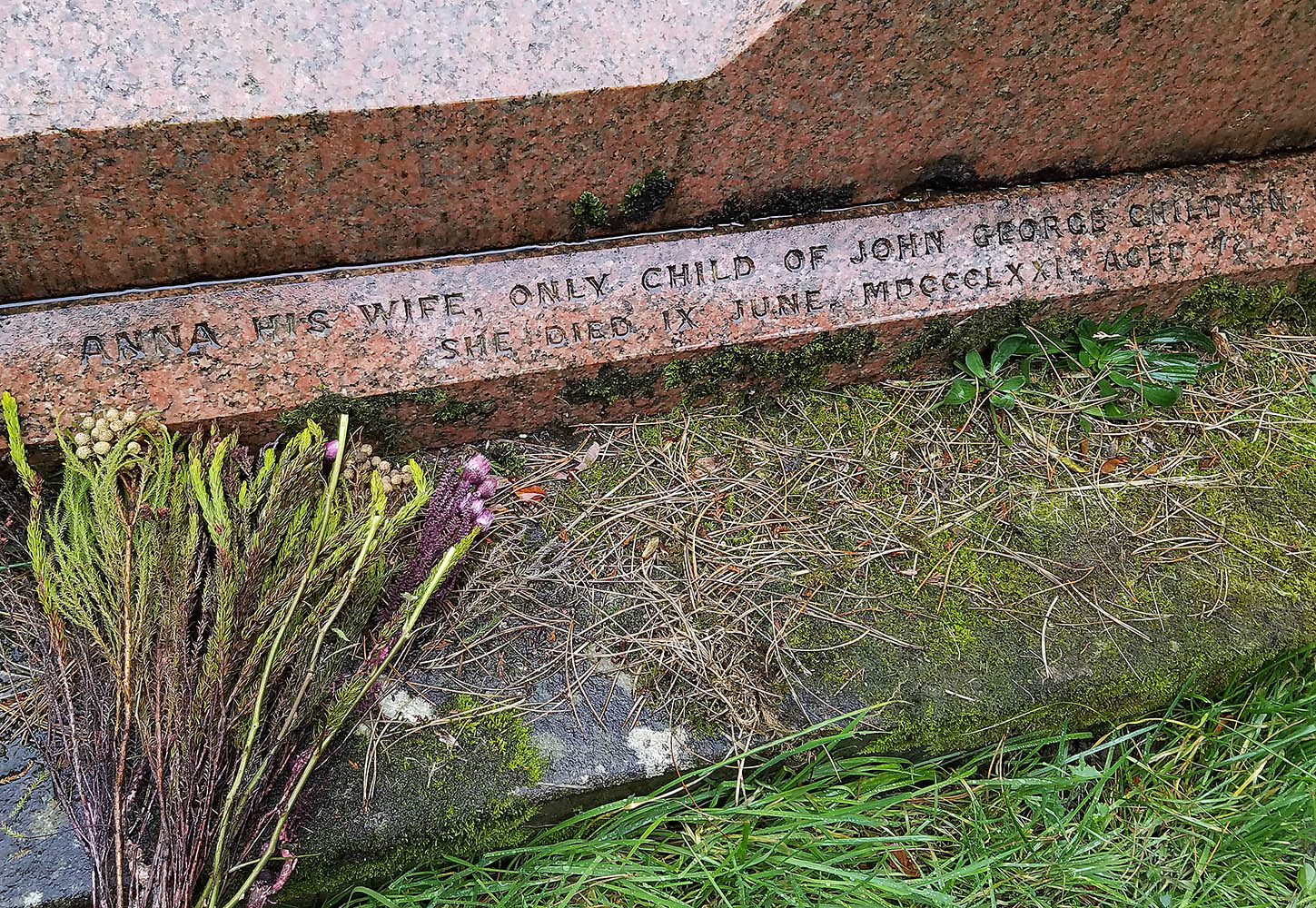

In March we celebrated the birth of Anna Atkins in 1799 and now we pay tribute to her death today, 9 June, in 1871.

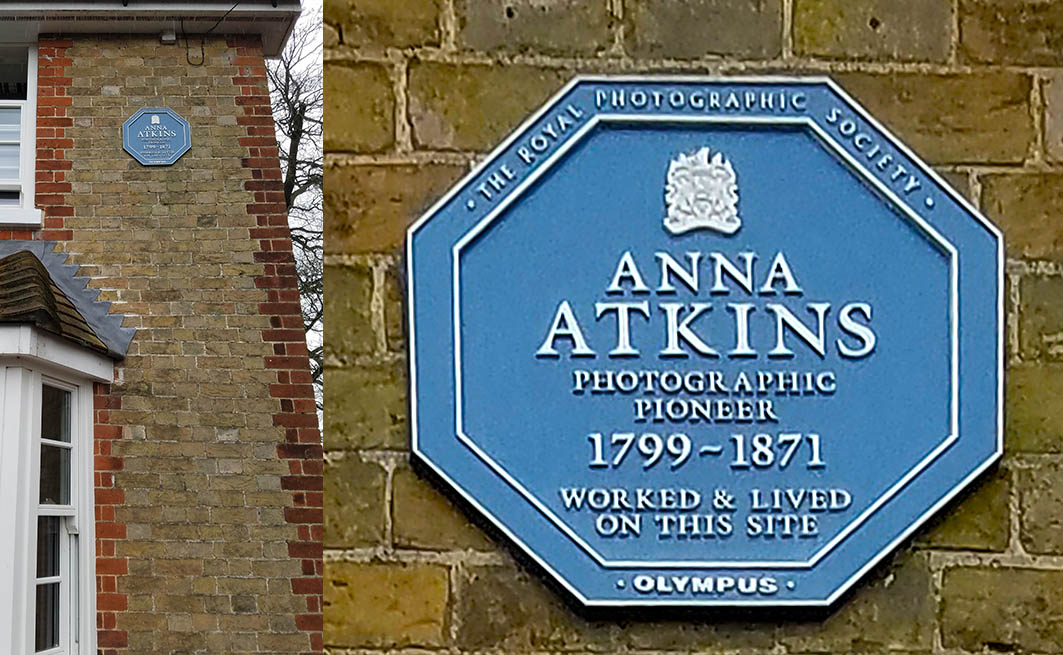

She is buried near her home of Halstead Place, near Sevenoaks in Kent. It served several purposes after the family left and the only significant part of it that now survives is the Stable Block and Coach House. However, in recent times, a blue plaque was installed on the Gate House, curiously best positioned for the gaze of giraffes, but at least giving her some recognition.

We have discussed Atkins work before, and undoubtedly will return to it in future, but for today let me once again praise the insight, courage, and hard work of the woman who first took on the task of using photographs to illustrate a serious scientific publication. She was encouraged in this effort by her widower father, John George Children, with whom she had the closest of intellectual ties.

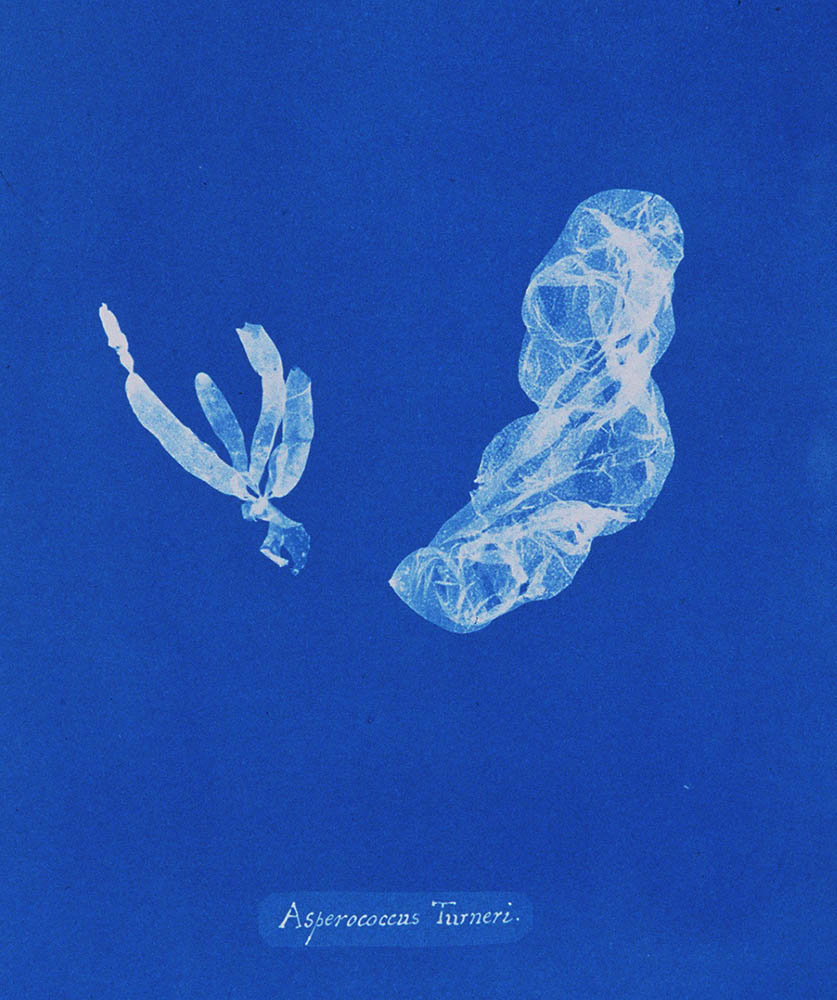

Like Henry, Children’s visage was preserved by a Richard Beard daguerreotype, but his affinities were more with Talbot than with Daguerre. Indeed, it was Children who chaired the meeting of the Royal Society in February 1839 when Talbot fully disclosed the working details of his photogenic drawing process. British Algae was a part book first issued in 1843, a year before Talbot commenced publishing The Pencil of Nature, but the two were friends and certainly never viewed this as a competition. It seems most appropriate to memorialize her with one of her own ‘Flowers of the Sea’.

Anna Atkins, Asperococcus Turneri, published in British Algæ, Cyanotype Impressions

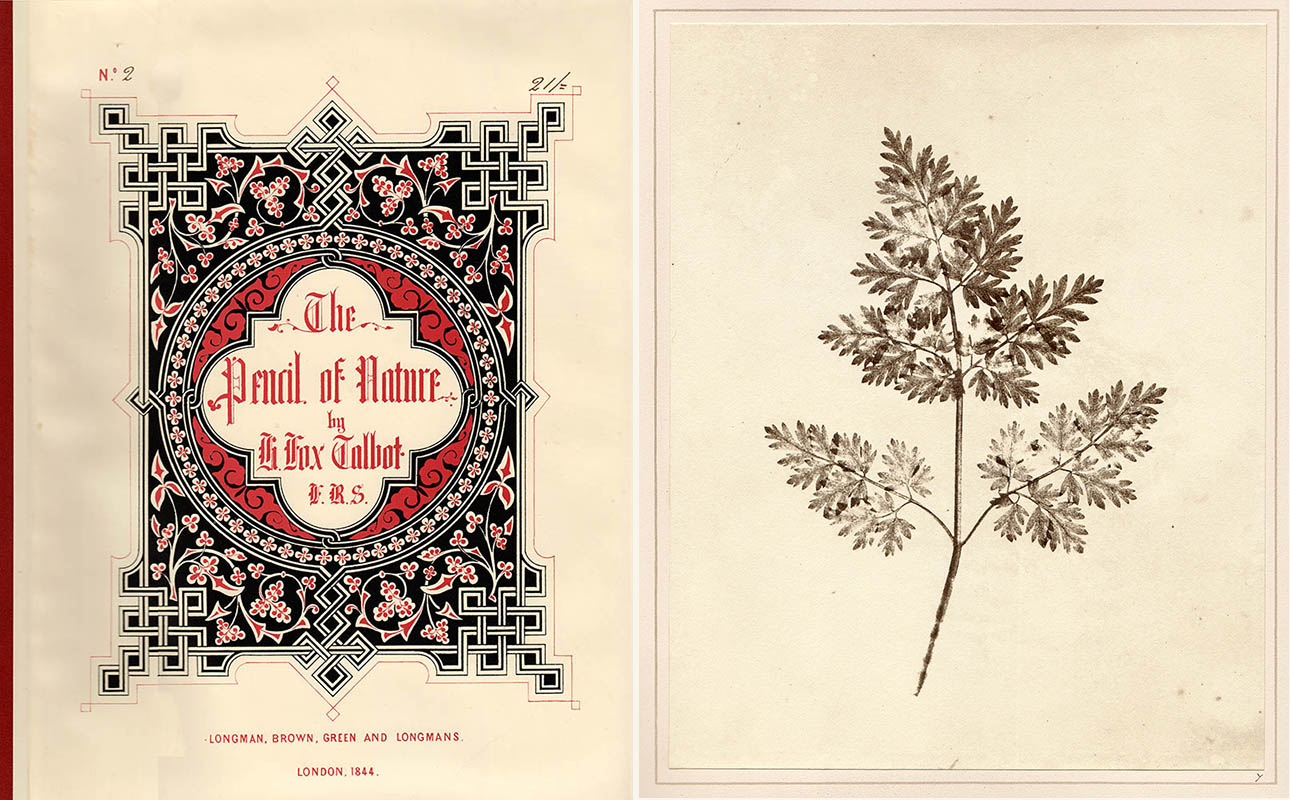

The reproduction of botanical specimens was one of Talbot’s most repeated subjects, particularly in the early days. Heavily influenced by his mother, Lady Elisabeth, and his favourite uncle, William Thomas Horner Fox Strangways, young Henry took to botany while still in short pants and it continued as a passion throughout his life. May I return to a letter quoted in an earlier blog? On 26 March 1839, just as the public was first becoming aware of photography, Talbot wrote to his botanist friend and mentor William Jackson Hooker, asking “what do you think of undertaking a work in conjunction with me, on the plants of Britain, or any other plants, with photographic plates, 100 copies to be struck off, or whatever one may call it, taken off, the objects?”

That 1839 publication was never realised, but Talbot did include an example in The Pencil of Nature.

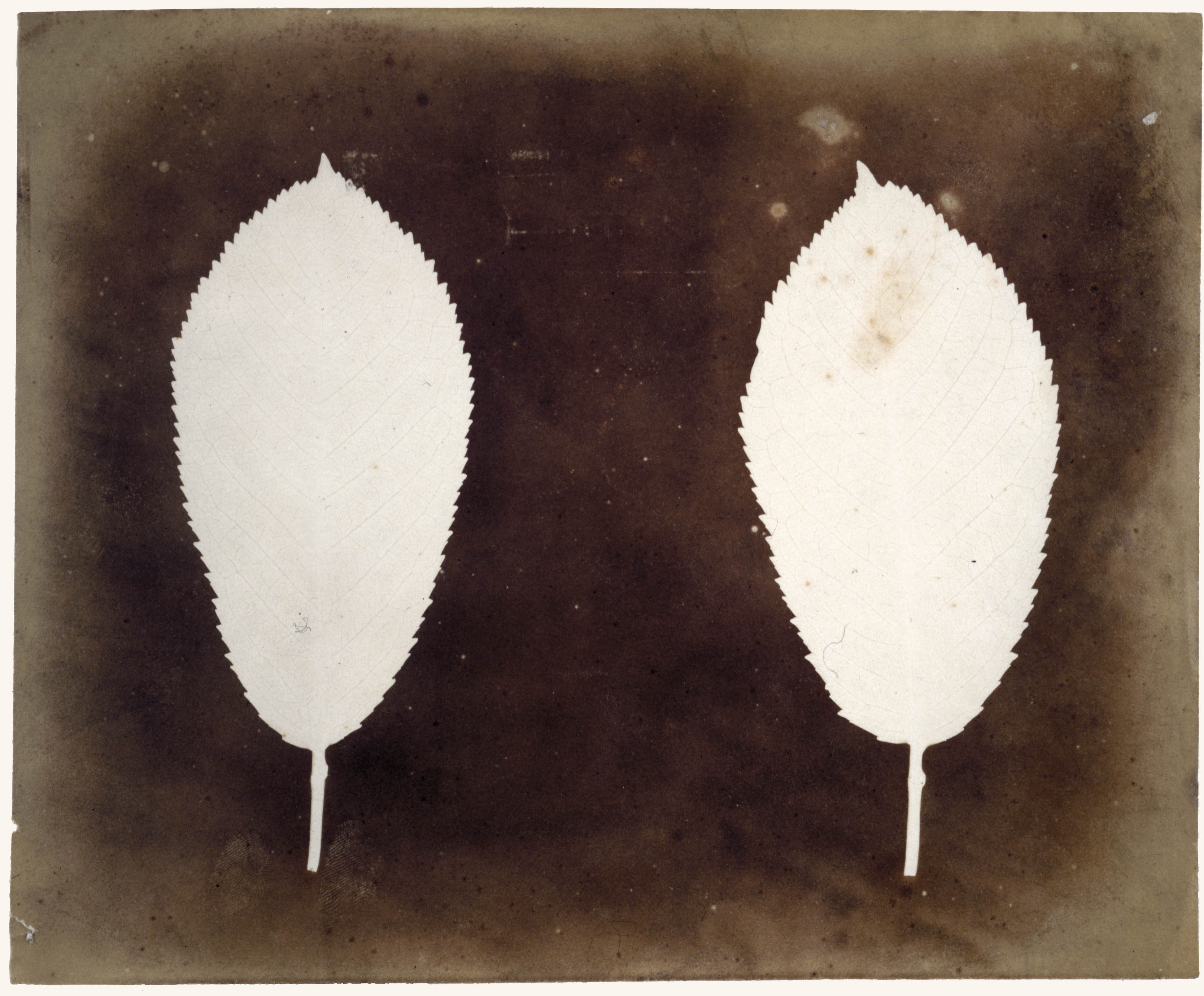

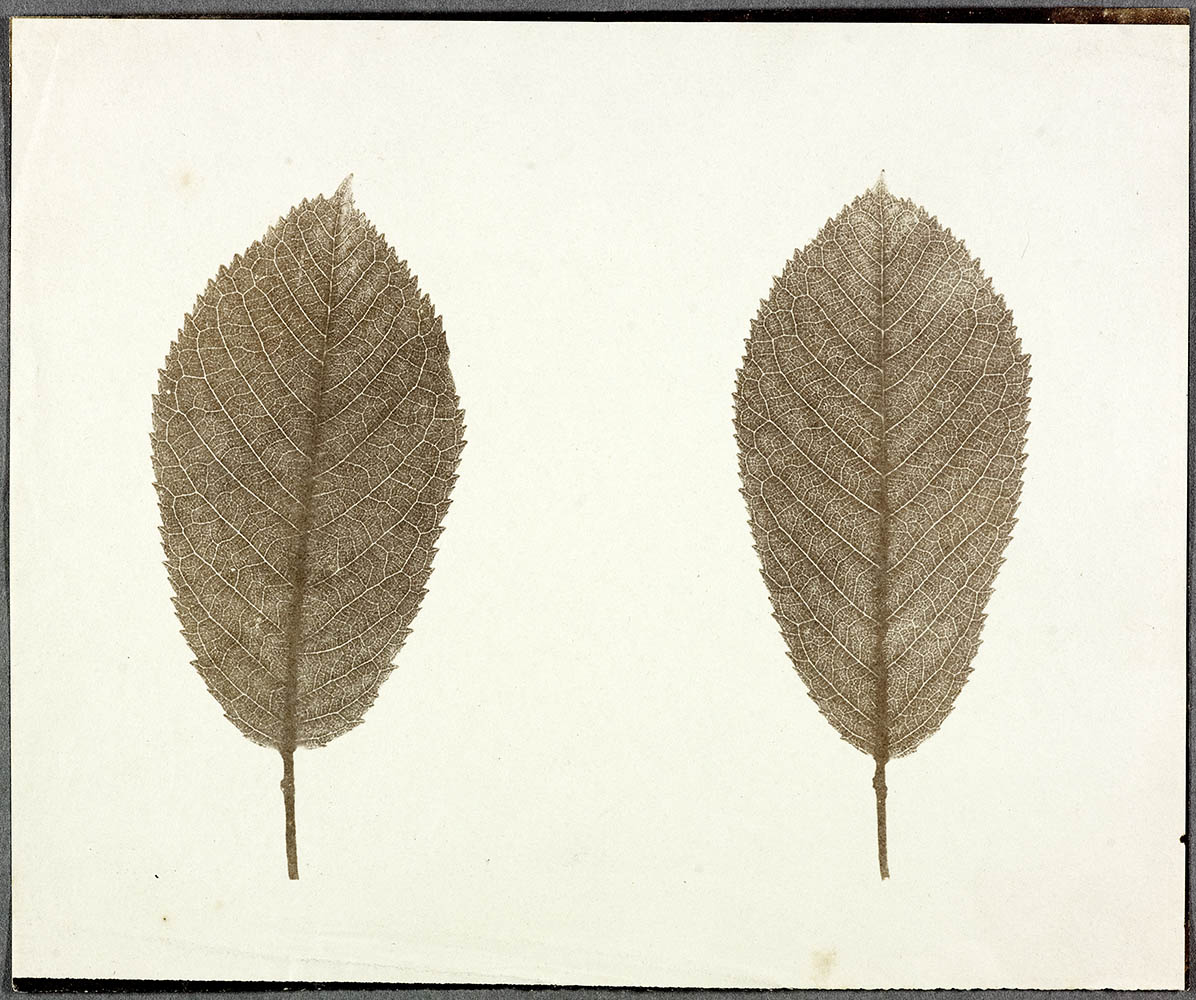

Plate VII, Leaf of a Plant, was included in fascicle two of The Pencil of Nature when it was published in January 1845. By then one might think that such simple objects were so commonplace as to be unsurprising, but we have to keep in mind that in the sixth public year of photography many people still had little idea what it could do. Talbot turned to his original process of photogenic drawing, explaining that “Hitherto we have presented …objects, obtained by the use of a Camera Obscura. But the present plate…is effected by a different and much simpler process…. A leaf of a plant…is laid flat upon a sheet of prepared paper…placed in the sunshine for a few minutes…then removed into a shady place, and when the leaf is taken up, it is found to have left its impression or picture on the paper…. The leaves of plants thus represented in white upon a dark background, make very pleasing pictures… but the present plate…speaking in the language of photography…is a positive and not a negative image…the change is accomplished by simply repeating the first process….” The critic for the Literary Gazette observed that “the leaf of a plant … is nature itself—how valuable for botanical science!”

The choice of the photogenic drawing process was a logical one for this subject. Its lower sensitivity to light than the more complicated calotype was actually an advantage because it was more forgiving of exposure times. Also, the calotype paper was best exposed whilst damp, an obvious drawback for contact printing.

So, how do we date this lovely negative of two leaves of the cherry tree? Had you asked me thirty or forty years ago I would have reflexively said “ca. 1839.” Not earlier, because it is hypo fixed, a technique that Talbot gained from his friend Sir John Herschel. But not much later either, for long ago I would have made the simple assumption that Talbot and the public turned more towards camera images as they became more practical. Although this negative has an ironclad provenance, it carries no independent information as to its date of production – references to ‘leaves’ in Talbot’s manuscripts are so broad as to be of little use.

But as the Catalogue Raisonné progresses, more and more correlations are brought to light. There is at least one print extant made from this negative.

Lacking watermarks or Talbot inscriptions, this doesn’t really help on the dating. There is yet another correlation, a negative with the same two leaves in a different arrangement, but once again, it offers few clues.

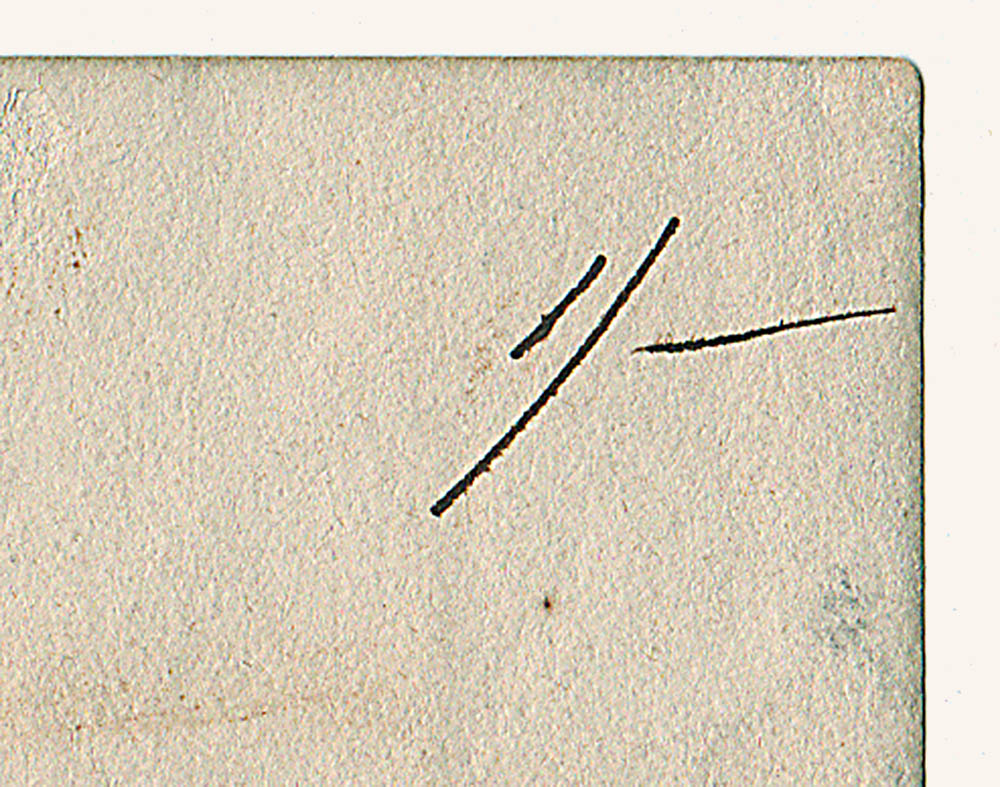

But both of these yield one tiny hint that takes us away from 1839 and indeed steers us away from Talbot. The print and the variant negative carry an ink inscription on the verso:

Talbot greatly valued his negatives and prints but as a gentleman he would never think of pricing or selling them. The one shilling price inked on these latter two examples prove that they were headed for the marketplace. The most obvious thought is that these were done by Nicolaas Henneman (or his studio) sometime after he set up in Reading in late 1843. By the time he transferred his operations to London in late 1846, one would expect that demand for simple subjects like this would have been dropping off. Of course, you could argue that is why they weren’t sold and eventually became part of the Lacock Abbey collection. So today a ‘mid-1840s’ dating and an attribution to Henneman would be more to my fancy.

But we can’t leave the situation that simple, can we? Although Henry would never have sold any of his prints or negatives, the women of his family volunteered for various bazaars in support of Irish schools and Polish refugees. Most of the priced prints offered by Henneman, especially the mounted ones, had their price written on verso in pencil, presumably to allow for the possibility of market price adjustments. The two examples above are not mounted and are priced in ink. So I would hold out the possibility that they might have been earlier examples made by Talbot. Could Henry have donated some of his own early photographs towards his family’s participation in these worthy causes?

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Studio of Richard Beard, John George Children, daguerreotype, ca. 1841-1842, private collection. • Anna Atkins, Asperococcus Turneri, cyanotype published in British Algæ, Cyanotype Impressions; from Sir John Herschel’s copy in the New York Public Library. • WHFT to William Jackson Hooker, 26 March 1839; Talbot Correspondence Document no 03845. • WHFT, Leaf of a Plant, plate 7, and the cover for fascicle two of The Pencil of Nature, January 1845; courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jnr, New York. • Literary Gazette, no. 1463, 1 February 1845, p. 73. • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Two Leaves of the Black Cherry, photogenic drawing negative, mid-1840s, William Talbott Hillman Collection, courtesy of the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; Schaaf 4202. • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Two Leaves of the Black Cherry, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, mid-1840s, Media + Science Museum, Bradford, 1937-2022; Schaaf 4202. • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Two Leaves of the Black Cherry, photogenic drawing negative, mid-1840s, Media + Science Museum, Bradford, 1937-2094; Schaaf 2012.