.

Amongst his many talents, Henry Talbot had a lifelong interest in botany, one inspired by his mother Lady Elisabeth and reinforced by several extended family members. Thus, it is not surprising that he turned to the plants in his gardens as subjects for his early photographs, and equally unsurprising, given his love of books, that the plates in his library also were employed as ‘negatives’. He sometimes labeled his photographs, particularly in examples sent to fellow botanists, but more often than not they are like our family snapshots, so familiar to those who took them that there was no need to label them at the time, but mysteries to us now. While Lacock Abbey is still lush with gardens, they have evolved so much over the generations that we cannot count on them to provide an accurate idea of what Talbot cultivated. Indeed, in an earlier blog we saw how one of his negatives enabled The National Trust to re-create his mother’s garden.

When you make your pilgrimage to Lacock Abbey (which you must do), the impressive array of bookshelves throughout the building will strike you. Sadly, most of them are not Henry’s books, instead coming from other branches of the family and other National Trust properties. The majority of his books, particularly the lavishly illustrated botanical volumes, were sold off in numerous sales dating back to the early twentieth century and extending into modern times.

Thus, identifying either the live plant or the botanical plate that Talbot employed as an original poses great challenges. As promised in an earlier blog, Dr Stephen A Harris now outlines some of the tools that might be used to meet these challenges

LJS

Guest Post by Dr Stephen A Harris

Dr Harris is Druce Curator of Oxford University Herbaria, a University Research Lecturer in the Department of Plant Sciences and Lecturer at Christ Church College. Stephen has a wide range of research interests in plant evolutionary biology, population genetics and field botany. He teaches undergraduate courses in plant identification and species conservation. Stephen has published extensively on the history of botany, botanical illustration and collecting, especially in the seventeenth century and eighteenth century. He has also published titles focused on the plants in our lives, such as Planting Paradise (2011), Grasses (2014) and What have plants ever done for us? (2015). Dr Harris is also intrigued by the possibilities of image recognition software, which led to this blog.

What’s that?

In mid-May I got an unusual request from Brian Liddy. It wasn’t unusual because Brian wanted to know the identity of some plants; it was unusual because of the material he asked me to identify. Brian asked whether any of the plants depicted in a small collection of images by Talbot came from the works of the Central European botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer. The question was easily answered in the negative; I know Bauer’s work very well. This of course left a question; if the images didn’t come from Bauer’s work then from whose work did they come?

Most plants I get to identify in my position as a herbarium curator are either living specimens or flattened, dried specimens; occasionally I work with fragments recovered from archaeological sites. However, whatever the plant material the processes of identification are similar but usually I am only concerned with identifying the plant species represented by a sample. In the case of the Talbot photographs, the sources of the image models were also of interest.

Identifying a plant

The best identifications are made using good-quality plant materials. If specimens are available, they should have spores, cones, flowers or fruits rather than just leaves. Furthermore, large specimens showing relationships among parts are easier to identify than separate pieces. If identifications are made from illustrations, the illustrations should be accurate; they need not be particularly beautiful or artistic.

Talbot’s use of pressed specimens in some cases creates images rather like traditional nature prints. Consequently, many of the details one naturally uses to identify plants, such as texture, hairs and venation, are lost. One has to rely on fundamental features such as overall leaf shape, leaf tip and base shapes and the type of leaf margin. In contrast, the illustrations Talbot chose to copy were by skilled botanical artists who understood accuracy; any identification issues with these images are associated with conventions in which they worked or the subtleties of characters that separate closely related species.

Some of Talbot’s leaf images are highly distinctive, e.g., Seseli libanotis (Schaaf no. 859) and Thalictrum minus (Schaaf no. 3663), others can only be broadly identified, e.g., Schaaf no. 1180 is the leaf of a member of the carrot family, probably a cultivated carrot, but can be placed no more precisely.

Other leaves are distinctive but the complexities of taxonomy mean accurate species identification based on the outline of one leaf would be unwise, e.g., Schaaf no. 1169 is a ladies mantle leaf, but which of numerous Alchemilla species cannot be said. Schaaf no. 4643, an image of two leaves and a flower, gives a few more clues. The flower have five petals, numerous stamens and a long stalk, whilst the leaves are compound and arranged opposite each other. Despite all the evidence, the best that can be made of the identification is that it is a species of Clematis. The problem here is because the genus is large, many species are grown in gardens, numerous cultivars have been selected, and we do not know where Talbot’s material was collected.

Plant identification from illustrations follows similar procedures, with the advantage that most of the plant parts necessary are present.

Identifying a source

Once a plant has been identified, there are some useful resources to try and locate sources. Index Londinensis (1929-1941) is a catalogue (arranged by species name) of plant illustrations in eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century botanical literature. To be used effectively one must know what plant names were called in the early twentieth century, which is where an online resource, The Plant List, is invaluable; it links synonyms to modern names. A modern website, with similarities to Index Londinensis, is Plantillustrations.org, which shows you images and has some synonym links in place. As a source of plant images the Biodiversity Heritage Library is especially useful.

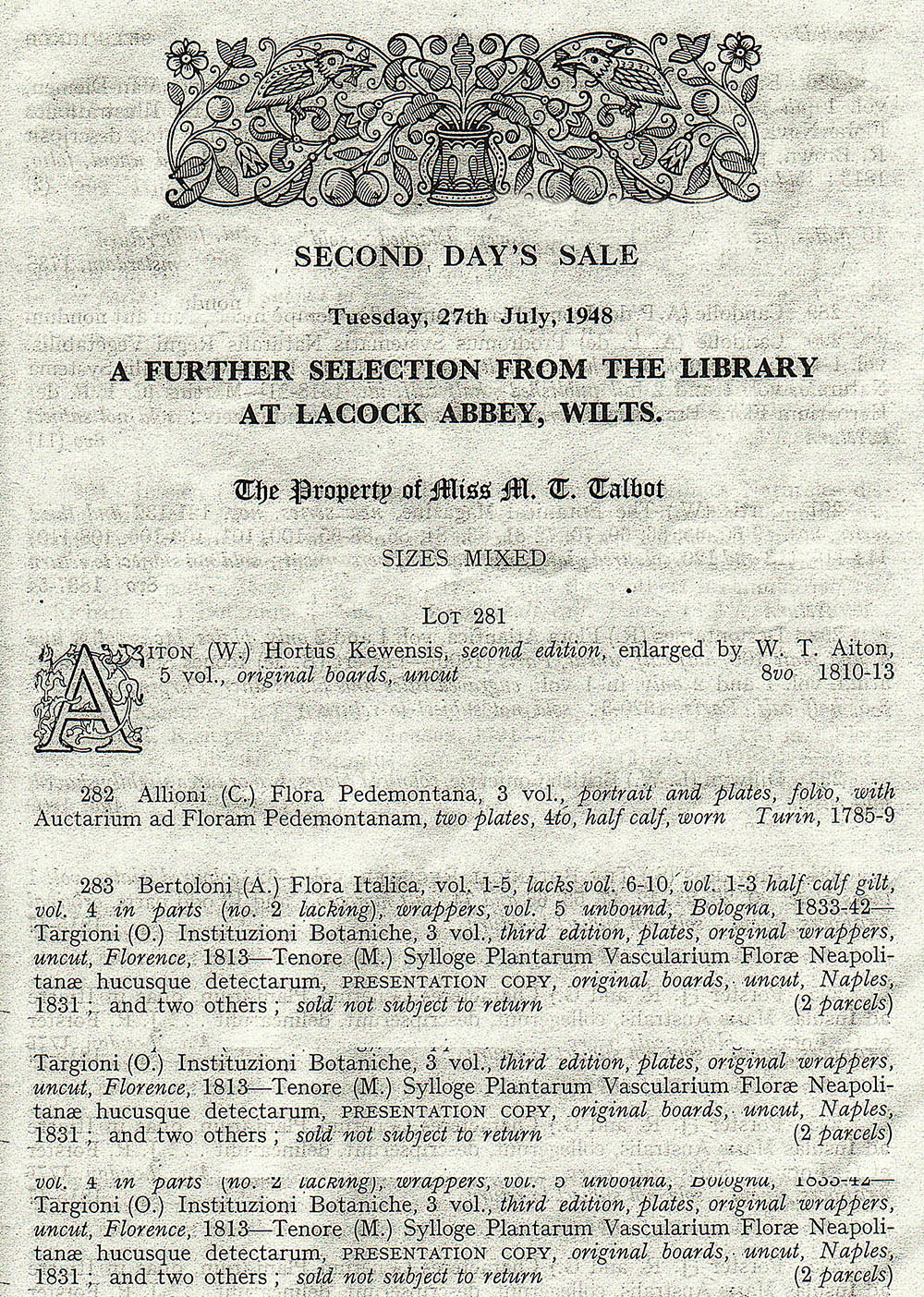

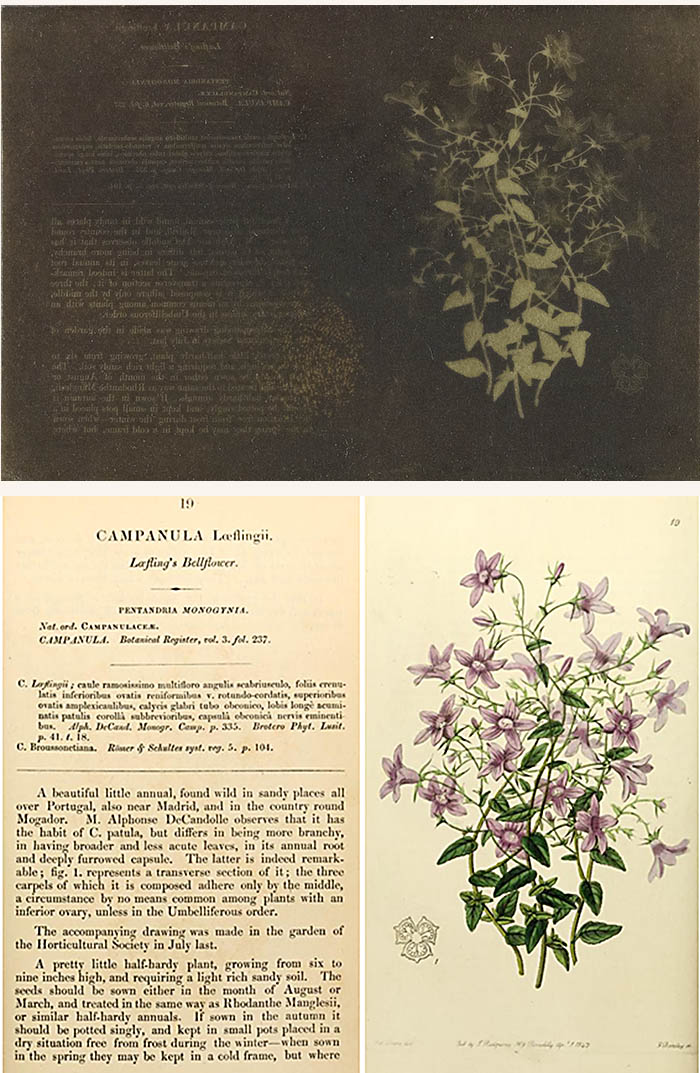

Schaaf no. 573 is a particularly haunting negative image of a lithograph of a bellflower (Campanula), with very prominent leaves and ghostly flowers. The plant is obviously a species of Campanula but the text in Talbot’s image is difficult to read. One the basis of the illustration it appeared to be Campanula lusitanica. However, all I could make out from the text heading was ‘Campanula loef…i’. This was enough to suggest the most obvious epithet was ‘loeflingii’, named in honour of Carolus Linnaeus’s unfortunate pupil Pehr Löfling who died in Venezuela in 1756 at the age of 27. This was not a species of Campanula I knew but a quick search of Index Londinensis came up with a reference to a coloured image in Edwards’s Botanical Register. A check of the herbarium library revealed the plate to be Talbot’s image, whilst The Plant List showed Campanula loeflingii is a synonym of Campanula lusitanica. The image was pinned down.

Other source identifications are the result of serendipity. Schaaf no. 339 is a metal etching of a member of the carrot family, labeled ‘Daucus aureus’. I recognised the image immediately, as I had been working with René Desfontaines’s Flora Atlantica (1798) a few weeks earlier as part of another research project.

However, among the victories there are some battles still to win. Schaaf no. 337 is an image of a lithograph of a sloe but I have not found the source. Similarly, Schaaf no. 1476 is a metal engraving of members of the scabious and carrot families with associated Latin phrase names.

Talbot helpfully inscribed this as “from an old botanical work” but a search of the standard pre-1753 sources has not revealed these names or the plate from where the image was taken. Finding these sources will probably be a case of stumbling over them but perhaps the clues in the image of “Pag 197” and “Tab. LXXII” will help.

There is enormous satisfaction in finding the original source of an image. However, as image recognition software develops and on-line databases of images and associated botanical metadata become more extensive, image matching will probably become routine.

Stephen A Harris

• If you have questions or comments about this posting Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Sothebys, London, 27 July 1948. • WHFT, Seseli libanotis, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2206/2; Schaaf 859; Thalictrum minus, photogenic drawing negative, Private Collection , Schaaf 3663. • WHFT, A Cultivated Carrot?, photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-365/40, Schaaf 1180. • WHFT, Alchemilla , photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-365/42, Schaaf 1169; WHFT, Clematis, John Dillwyn Llewelyn Collection, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford; Schaaf 4143. • WHFT, Campanula loeflingii , photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-365/42, Schaaf 573; Edwards’s Botanical Register (1843), v. 29, pl. 19. • WHFT, Daucus aureu , photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1056, Schaaf 339; René Desfontaines, Flora Atlantica (1798); v. 1, pl. 61. • WHFT, Sloe, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-1049, Schaaf 337. • WHFT, Photogenic Copy from an Old Botanical Work, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York, Schaaf 1476.