.

It is my annual duty to recognise the life of William Henry Fox Talbot, who passed away peacefully at Lacock Abbey on Sunday of this week, 17 September 1877. In past years, we have commemorated this day with an evocative cyanotype by John Dugdale and by using one of Talbot’s own photographs. Today’s contribution comes from my favourite Canadian daguerreotypist, Mike Robinson.

There is another life that we should celebrate this week, that of Henry’s great-great grandson, Anthony Burnett-Brown, who was born in 1930 and left us on Monday of next week, 18 September 2002. An Etonian with a love of mountaineering and beagling, when he built his first sailboat he named her Ela after the founding Abbess of Lacock Abbey. Anthony read maths at Corpus Christi, Oxford and was a member of the Rowing Eight. His subsequent professional life was as an actuary. Although soft spoken, he had a rich voice and was a singer, both in church and of Gilbert and Sullivan, which perhaps formed part of the reason that he married the internationally known singer and violinist, Petronella Dittmer. After 1971 Lacock Abbey became their home.

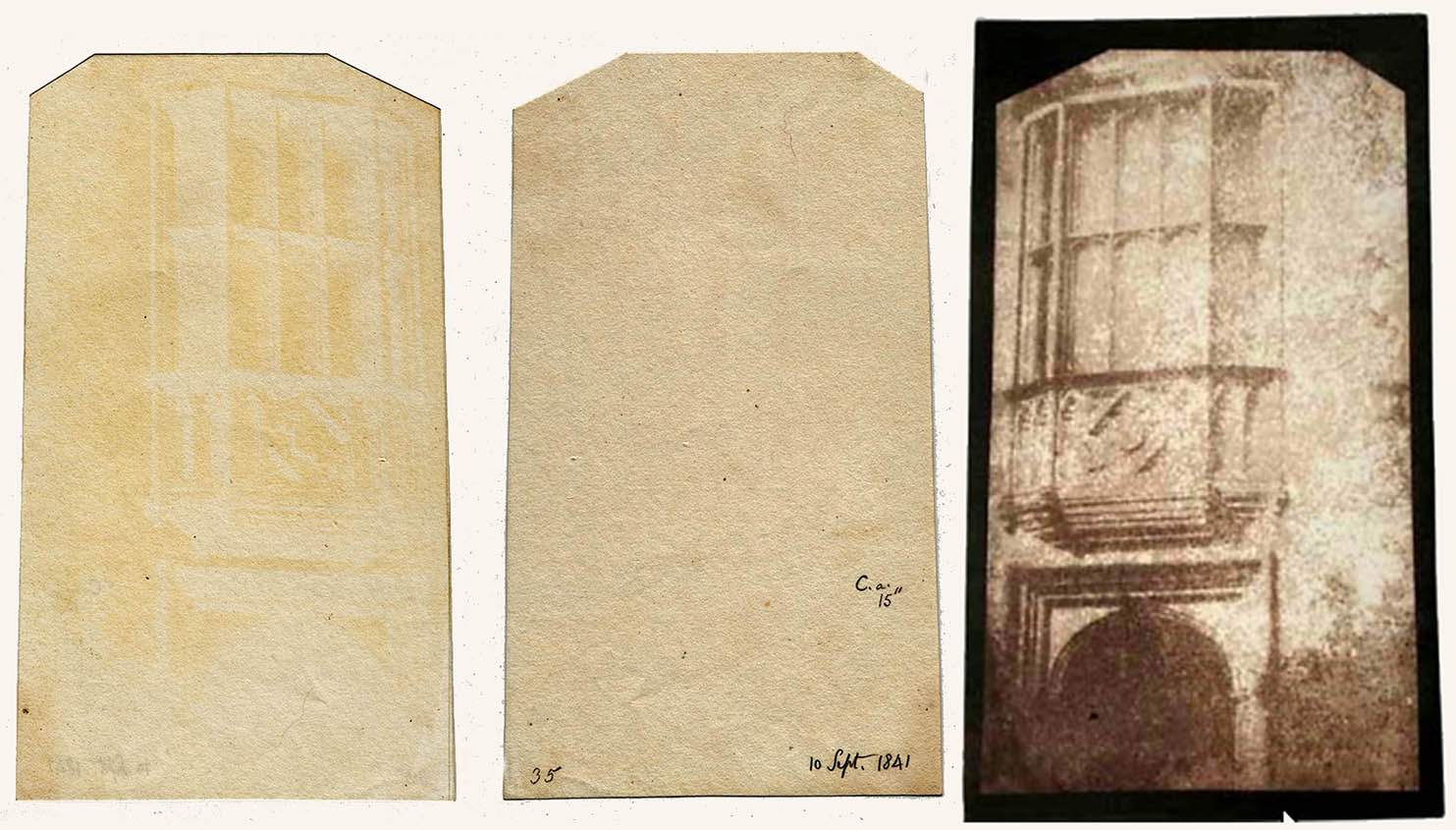

I probably would never have met Anthony without Talbot – and I certainly would never have come to know Henry Talbot so intimately without the wholehearted support of Anthony. We were slow in getting to meet each other, me a country bumpkin and Anthony by then retired and slowly growing into the task of becoming the caretaker of Henry Talbot’s legacy. This Talbot picture, taken on 17 September 1841, has always reminded me of one of my first contacts with Mr Burnett-Brown. I’ve told the story before about Harold White having sorted the letters in the Lacock Abbey collection into one large pile that he intended to draw on for his biography of Talbot and creating an equally large group of ‘doubtful use’ letters. It was in the late 1970s when I was spending the summer with Bob Lassam in the Fox Talbot Museum that I was ready to move on to this additional group. Harold White’s primary sorting was on deposit there but the ‘doubtful use’ group was still in the Abbey. Bob called Mr Burnett-Brown on my behalf and asked if I could see them. Anthony replied that viewing them in the Museum would perhaps be more convenient and that I should come and collect them. I crossed the field to the Abbey – only a couple hundred meters away – and as I approached the front door I could see that it was firmly closed. Sitting in the bright sunlight, just about where Charles Porter is standing in this image, were two bulging suitcases which I picked up and carried back to the Museum. The many hundreds of ‘doubtful use’ letters kept me busy the rest of that summer. At the end of my stay I offered to carry them back but Anthony said that it would be ok to simply leave them in the Museum. They stayed there until Anthony’s sister and widow made their extraordinarily generous donation of the contents of the Museum to the British Library where they are now integrated into the full run of correspondence.

I probably would never have met Anthony without Talbot – and I certainly would never have come to know Henry Talbot so intimately without the wholehearted support of Anthony. We were slow in getting to meet each other, me a country bumpkin and Anthony by then retired and slowly growing into the task of becoming the caretaker of Henry Talbot’s legacy. This Talbot picture, taken on 17 September 1841, has always reminded me of one of my first contacts with Mr Burnett-Brown. I’ve told the story before about Harold White having sorted the letters in the Lacock Abbey collection into one large pile that he intended to draw on for his biography of Talbot and creating an equally large group of ‘doubtful use’ letters. It was in the late 1970s when I was spending the summer with Bob Lassam in the Fox Talbot Museum that I was ready to move on to this additional group. Harold White’s primary sorting was on deposit there but the ‘doubtful use’ group was still in the Abbey. Bob called Mr Burnett-Brown on my behalf and asked if I could see them. Anthony replied that viewing them in the Museum would perhaps be more convenient and that I should come and collect them. I crossed the field to the Abbey – only a couple hundred meters away – and as I approached the front door I could see that it was firmly closed. Sitting in the bright sunlight, just about where Charles Porter is standing in this image, were two bulging suitcases which I picked up and carried back to the Museum. The many hundreds of ‘doubtful use’ letters kept me busy the rest of that summer. At the end of my stay I offered to carry them back but Anthony said that it would be ok to simply leave them in the Museum. They stayed there until Anthony’s sister and widow made their extraordinarily generous donation of the contents of the Museum to the British Library where they are now integrated into the full run of correspondence. 17 September 1841 (print enhanced)

17 September 1841 (print enhanced)

He was also terribly patient with my seemingly unending requests. I pointed out in an earlier blog when he finally triumphed in finding the Neapolitan Conveyance painting that Talbot had photographed. On another visit he welcomed me by opening his desk drawer and pulling out the long sought-after painted glass Head of an Unknown Saint. Lacock Abbey has been extensively modified since Talbot’s day, first by his son Charles Henry, who had portions restored to their state long before his father was born. The National Trust has made continual repairs and restorations, sometimes again taking things outside Henry Talbot’s time frame which makes identifying specific Talbot images problematic. I can’t count how many times Anthony and I would clamber about the roofs looking for just the right evidence.

Anthony bravely took on the multiple responsibilities of being curator, caretaker and researcher of Henry Talbot’s archive. And I must also pay tribute to his sister Janet who for many years patiently led the public tours through Lacock Abbey. She was the keeper of many family memories and someday I must do a blog on her accomplishments. There had been various attempts to form a museum at Lacock, at one time envisioned as being within the Abbey itself but ultimately, in 1977, it was established in the gate house at the entrance. Anthony and Janet were there from the founding and were always firm supporters of the Museum.

This week in September was a busy and productive one for Henry Talbot. His mother, Lady Elisabeth, displayed her active interest in his invention of photography and dutifully recorded in her 1841 diary:

[3 September] made photographs & Calotypes with Henry all the morning

[8 Sept] Fine brilliant day. Made Calotypes in the Cloisters

[9 Sept] damp dull day. Mr Collen came

[10 Sept] very fine day

[15 Sept] went with Henry to Bowood

[16 Sept] Henry went home

[17 Sept] returned to Laycock Abbey

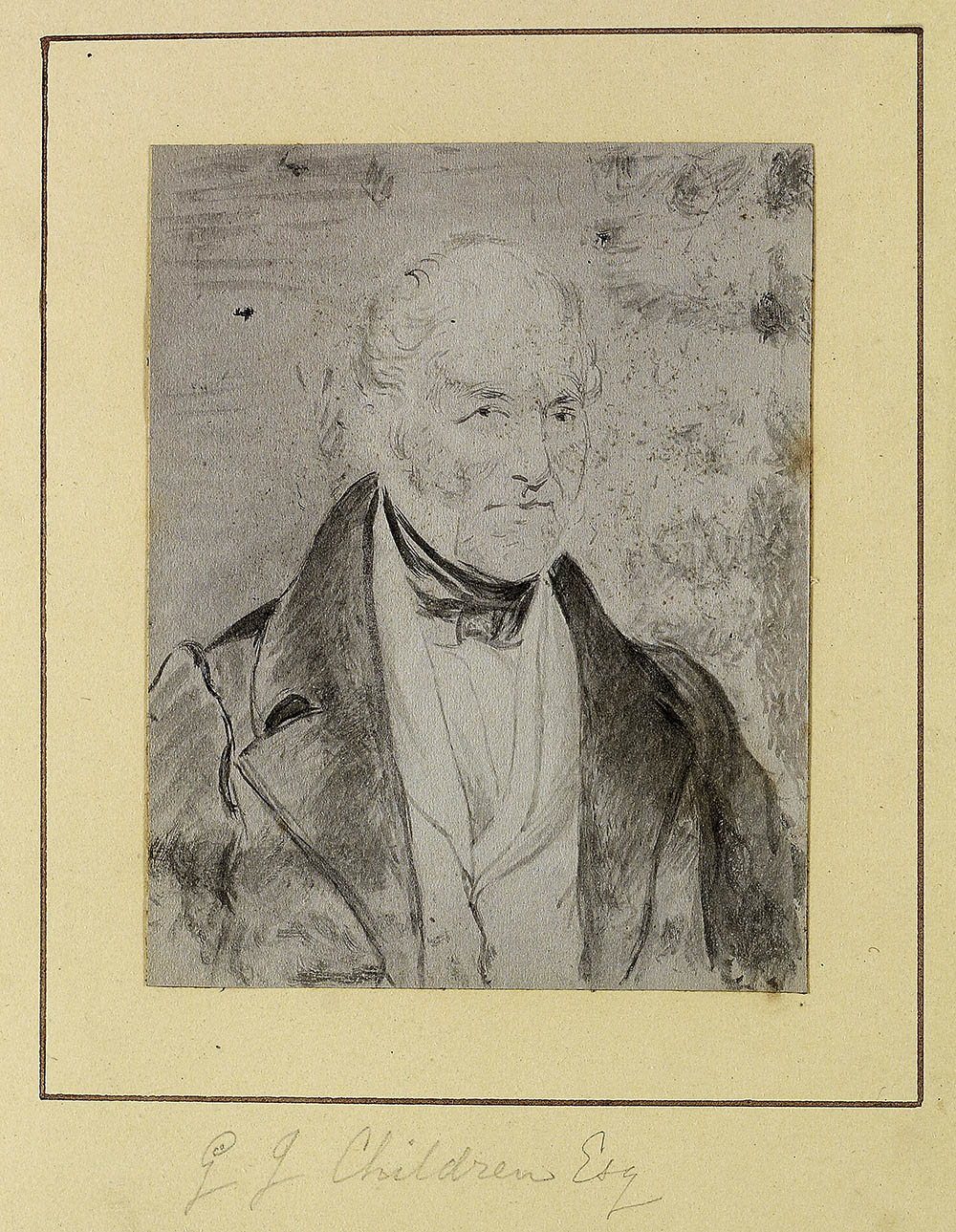

The visitor was Henry Collen (1800-1879), a London-based miniature painter to the Queen and later a spiritualist. He was the first person to take out a license to commercially practice the calotype – his prints are mostly glossed over these days because the underlying salt print has faded, leaving the caricature of his retouching (his story calls for another future blog). Just days after Collen visited Lacock Abbey he made a portrait of John George Children, Anna Atkins’s father, who wrote excitedly to Talbot:

“on my return to Town I found the Calotypes safe on my table – I do not know how to express my thanks, in adequate terms, for your obliging and prompt compliance with my request. The Specimens you have so liberally sent me, are beautiful, and when we return into Kent, My Daughter & I shall set to work in good earnest ’till we completely succeed in practising your invaluable process – I am also extremely obliged to you for introducing me to Mr Collen- from whom I have received much valuable information & I have sat to him for my Calotype this morning. I have also ordered a Camera for Mrs Atkins from Ross – so I hope on our return from Leicestershire (where I am to join them tomorrow) about the middle of next Month, we shall find all ready to commence operations – For the traveller, your process is beyond all price, and in my estimation your Calotype Portraits, are incomparably superior to those by the Daguerotype [sic].”

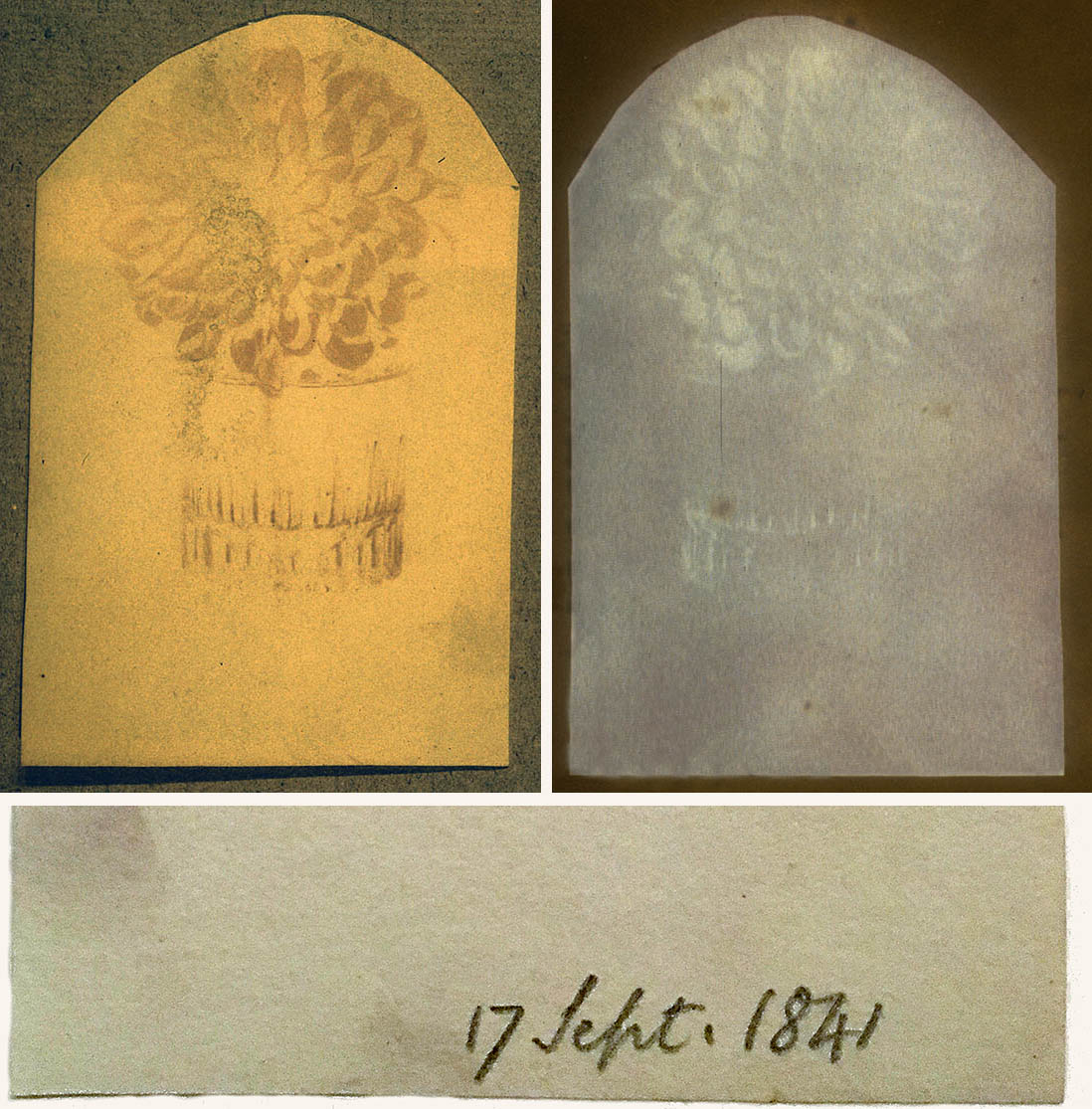

And we’ll end with a floral tribute to these two fine men, another Talbot photograph from 17 September, the day that Lady Elisabeth recorded that Henry returned to Lacock Abbey after photographing at his uncle’s Bowood House.

And we’ll end with a floral tribute to these two fine men, another Talbot photograph from 17 September, the day that Lady Elisabeth recorded that Henry returned to Lacock Abbey after photographing at his uncle’s Bowood House.

Now, I don’t have a modern calotype of Talbot’s gravestone and surely someone must have taken one. It will be my duty to celebrate the 17th of September next year and I would like to balance out Mike Robinson’s daguerreotype with a photograph taken by Talbot’s own process. If you have done one already, please send it along, and if you have not I will expect hordes of modern calotypists to descend on Lacock’s graveyard over the course of next year, sensitised paper in hand.

Now, I don’t have a modern calotype of Talbot’s gravestone and surely someone must have taken one. It will be my duty to celebrate the 17th of September next year and I would like to balance out Mike Robinson’s daguerreotype with a photograph taken by Talbot’s own process. If you have done one already, please send it along, and if you have not I will expect hordes of modern calotypists to descend on Lacock’s graveyard over the course of next year, sensitised paper in hand.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Charles Porter at open door, West Front of Lacock Abbey, 17 September 1841; calotype negative courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, NY; enhanced salted paper print, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/54; Schaaf 2624. • John George Children to WHFT, 14 September 1841, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 04332. • Henry Collen, G J Children Esq [sic], retouched salt print from a calotype negative, 14 September 1841, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-367/9. • WHFT, Oriel Window over doorway, South Front, Lacock Abbey, 10 September 1841; calotype negative, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.206.68; salted paper print, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London, LA937; Schaaf 2621. • WHFT, Dahlias in a tumbler, 17 September 1841, calotype negative and salted paper print, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 2623.