A new section of the website

with a new task for you

( please )

We are going to have to celebrate at least a couple of significant anniversaries during this month of October. For the first of them, a year ago almost to the day we note the 183rd anniversary of Talbot’s inspiration to invent the art of photography. It was such a critical event, both for Talbot and eventually for society, that I think we should celebrate it again.

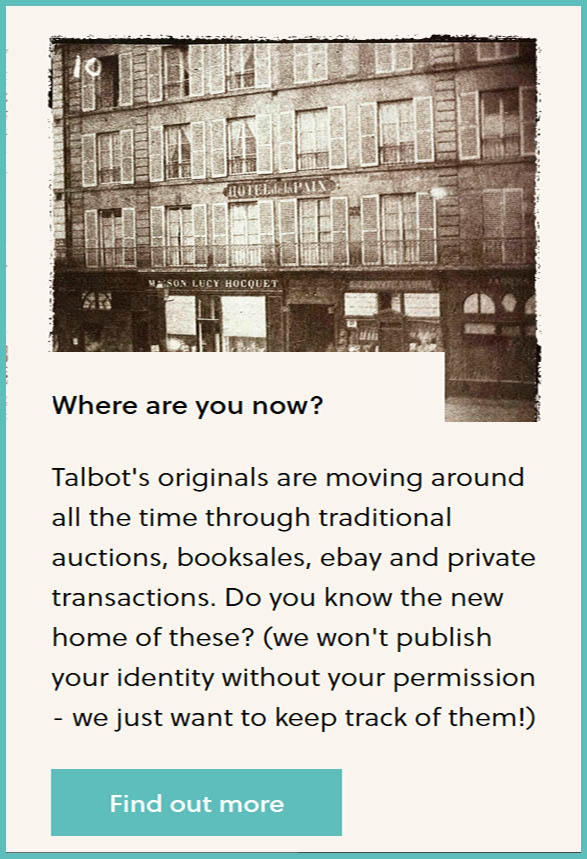

There is a much fuller explanation of this episode in last year’s post, but I’ll take the liberty of once again reproducing Henry Talbot’s finest piece of draughtsmanship, his 5 October 1833 camera lucida drawing, the one that finally convinced him that it was time to hand the pencil over to Nature. He perched on the front steps of the Villa Melzi, near the fishing village of Bellagio on the shores of Lake Como and pulled out the camera lucida. One of these instruments had been his travelling companion for years, but this was probably the new one that he had just purchased from Chevalier in Paris in late June. However, his desperate appeal to technology failed him, leading Henry to recall years later in The Pencil of Nature that “the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.”

There is a much fuller explanation of this episode in last year’s post, but I’ll take the liberty of once again reproducing Henry Talbot’s finest piece of draughtsmanship, his 5 October 1833 camera lucida drawing, the one that finally convinced him that it was time to hand the pencil over to Nature. He perched on the front steps of the Villa Melzi, near the fishing village of Bellagio on the shores of Lake Como and pulled out the camera lucida. One of these instruments had been his travelling companion for years, but this was probably the new one that he had just purchased from Chevalier in Paris in late June. However, his desperate appeal to technology failed him, leading Henry to recall years later in The Pencil of Nature that “the faithless pencil had only left traces on the paper melancholy to behold.”

The Kodachrome above shows my wife Elizabeth’s camera lucida, set up for pretty much the same view. It was on a sultry day in the middle of July 1985 when we were in Verona, doing on-press proofing of Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins. Martino Mardersteig’s Stamperia Valdonega was doing its typically fine job so we slipped away for a couple of days to Bellagio, climbing its steep hilly streets to the Villa Roma, an albergo surely rated half-star at most but absolutely charming and family run. The next morning we walked the few hundred meters to Villa Melzi, passing the fertile Koi ponds on the way through the show gardens. I believe that it is much the same today.

The magic of a pencil drawing derives from its creator’s ability to distill all the elements of this and integrate them into monochromatic line and form on a flat sheet of textured paper. I may have mentioned before that I am the Henry Talbot of our family. I can fully describe a camera lucida – I can even build one from scratch. I understand perspective, as did Talbot. I can analyze the stones of Bellagio’s walls and the lapsed photographer in me observes the angles and interplays of light and shadows. But in my hands the pencil has always been as faithless as was Talbot’s.

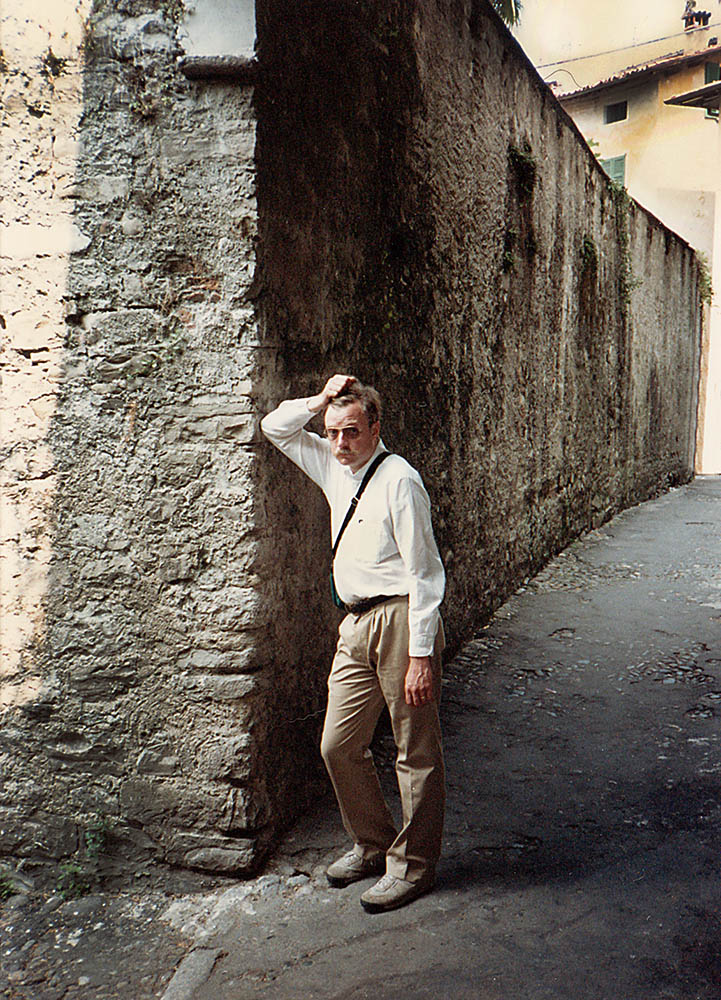

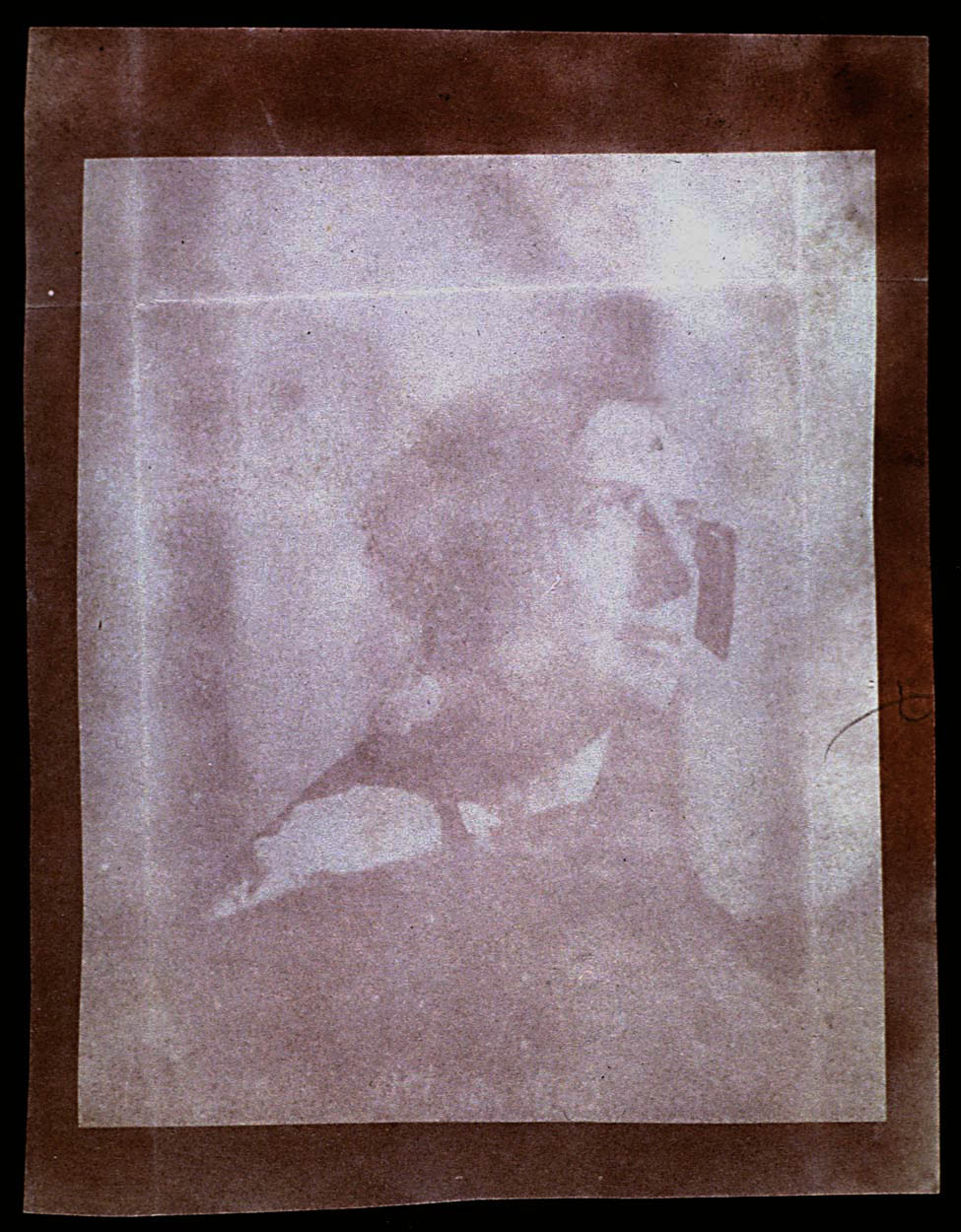

By October 1839, when photography had become public, Talbot was experimenting with all sorts of variations of his photogenic drawing process. This negative may not look like much today, but it directly correlates with one of the entries in his Notebook P and this might explain its strange appearance: “A picture made October 20 on Waterloo paper fixed with salt makes good transfers [prints]. The wrong side of the paper was placed outermost in the camera has this any thing to do with the result?” Once dry, the chemical coating on the plain paper was very difficult to perceive – from this point forward, we commonly see Talbot first placing a pencil X on the side that he intended to coat.

By October 1839, when photography had become public, Talbot was experimenting with all sorts of variations of his photogenic drawing process. This negative may not look like much today, but it directly correlates with one of the entries in his Notebook P and this might explain its strange appearance: “A picture made October 20 on Waterloo paper fixed with salt makes good transfers [prints]. The wrong side of the paper was placed outermost in the camera has this any thing to do with the result?” Once dry, the chemical coating on the plain paper was very difficult to perceive – from this point forward, we commonly see Talbot first placing a pencil X on the side that he intended to coat.

Constance, lit through blue glass for a 30 second exposure, 10 October 1840

Constance, lit through blue glass for a 30 second exposure, 10 October 1840

I’ve written at more length about this early portrait of Constance but once again marvel at what today has become so commonplace. Talbot’s newly-discovered calotype negative paper saw only blue light, so the filtering (suggested by Sir John Herschel) blocked many of the glaring heat rays from Constance’s eyes. The wooden chair stood in for the iron clamps favoured by daguerreotype studios. But the real marvel was capturing the image of a loved one in half a minute at a time when perhaps one or two painted portraits might have been executed in a lifetime.

Nicolaas Henneman, reading by candlelight, 2 October 1841 (digitally enhanced)

Nicolaas Henneman, reading by candlelight, 2 October 1841 (digitally enhanced)

Caroline Consoling Horatia, 19 October 1842 (negative and digital print)

Caroline Consoling Horatia, 19 October 1842 (negative and digital print)

One of a series of portraits taken around this time, Henry Talbot has succeeded in capturing a more lifelike rendition of a tender moment between two sisters.We know from Lady Elisabeth’s diary that in October of 1842 “Caroline arrived on 15th & C. and Horatia went to Bowood on 18th” – whether this was taken there or at Lacock Abbey is unclear.

Unfortunately at present all known forms of records for October 1843 are sparse, with only a handful of letters and technical notes and perhaps more significantly, not a single positively identified photograph attributable to this month. Was it the weather? Or Talbot’s other activities? There is a slight clue in a letter from John Burnell, a processor of horns, which details their efforts to use thin sheets of horn such as those employed in lanterns as a relatively clear base for photographic negatives. It would have avoided the fragility of glass and the fibrous texture of paper but apparently finally proved impractical

Villa Melzi’s lion confronts Talbot’s negative of Scott’s Maida

As a time for photography, the early autumn rays of light for October had been stimulating to Talbot. Nowhere was this more evident than in October 1844 when he ventured north of Hadrian’s Wall. In October 1833, the lions at Villa Melzi could barely suppress their mockery of his attempts at draughtsmanship. Eleven years later Henry Talbot had become a master of his own photographic art. Later in this month we’ll have another little birthday party for the results of this trip, both the published and unpublished photographs for his second book, Sun Pictures in Scotland.

October was indeed a good month for Henry Talbot.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Villa Melzi, camera lucida drawing, pencil on paper, 5 October 1833, Talbot Collection, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2537/4. • WHFT, Sharington’s Tower, Lacock Abbey, photogenic drawing negative and digital print, 20 October 1839, The National Gallery of Canada, P72:169:37; Schaaf 2308. • WHFT, “C’s portrait, 30″ blue glass” , Royal Photographic Society Collection, the Victoria & Albert Museum, RPS25130; Schaaf 2503. • WHFT, Nicolaas Henneman, reading by candlelight, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 2 October 1841, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London; Schaaf 2627. • WHFT, Caroline consoling Horatia, calotype negative and digital print, 19 October 1842, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-3634; Schaaf 2692. •. John Burnell to WHFT, 4 October 1843, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no 04882. •

P153