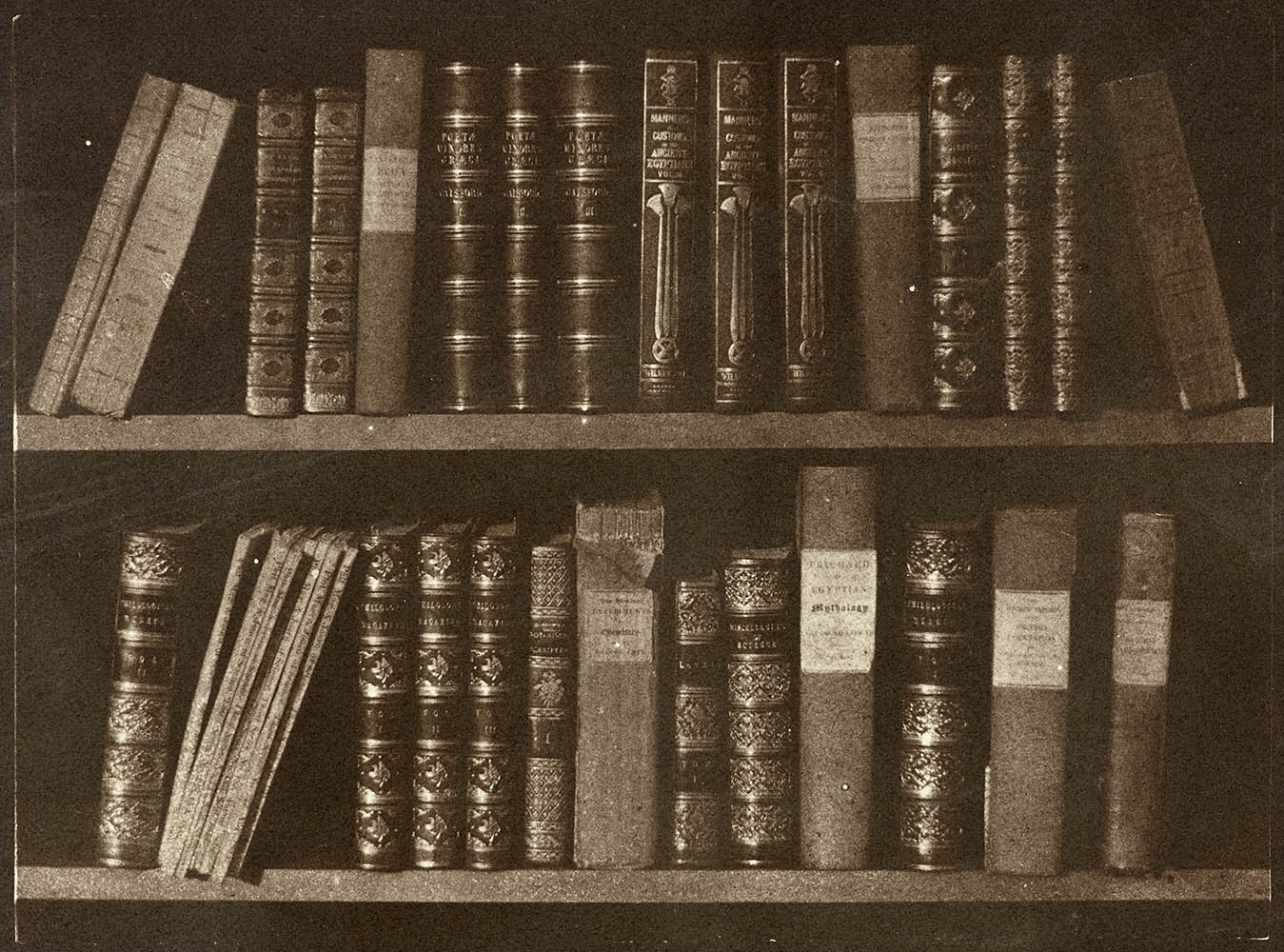

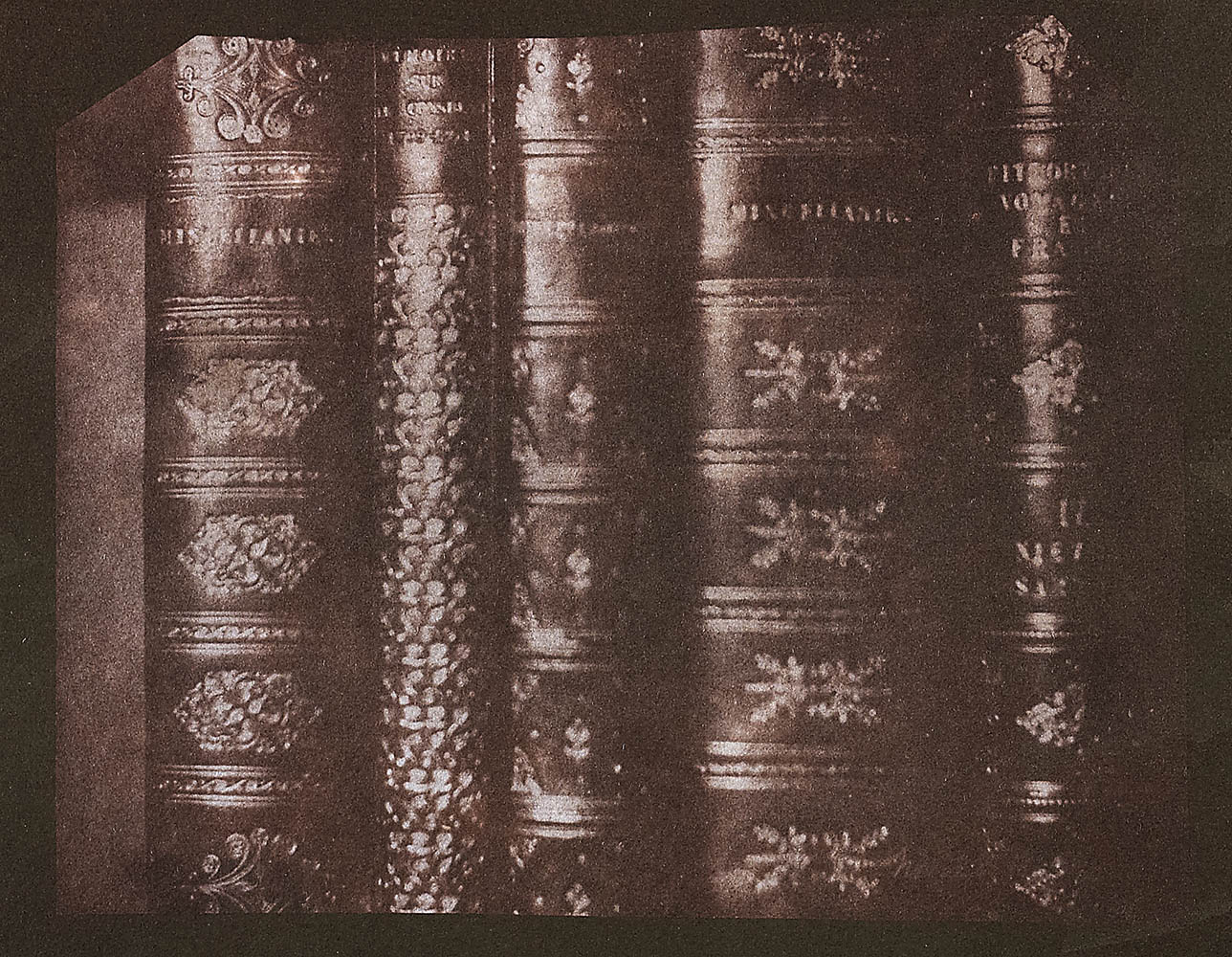

Talbot’s death in 1877 drew out a vivid memory for an unidentified contributor to the Daily Telegraph: “some eight-and-thirty years ago there used to be visible in the corner of an optician’s shop window in Regent street, a pale and dingy vignette on which, probably, few passers-by ever cared to bestow a glance…the little picture somewhat puzzled the inquisitive, since, with all their lengthened experience, they were fain to confess that they had never seen anything of the same kind before anywhere else. It was on a thin yellowish paper, and its hue was the monochrome of an uncertain bistre; but whether the thing itself was a mezzotint engraving, or a lithograph, or an Indian ink drawing, none but the initiated – and the fláneurs were not yet initiated – could tell. It represented only a few shelves full of variously bound books; but the marvel about it was that every particular volume, from bulky folios to ‘ragged back’ paper pamphlets, was delineated with an accuracy of draughtsmanship and a microscopic fidelity in texture and detail which might have aroused the envy of Gerard Douw or a Wilkie. No modern pre-Rafaellites ever produced such exquisite ‘finish’ as was visible in the contents of those miniature shelves; and, abating the depressing sepia tint pervading the whole, the books looked alive – as much as objects of still life could look indeed.”

He must have been recalling an early version of one of Talbot’s most iconic plates in The Pencil of Nature.

In 1814, writing from Harrow, young Henry proudly informed his mother that “As a monitor, I have access to the School library; which consists of two rooms, each about twice as big as my study. – the books in them are parting presents of Harrow boys, & some of them are very nice ones: – classics, & English poets.” His fondness for books was to remain throughout his life.

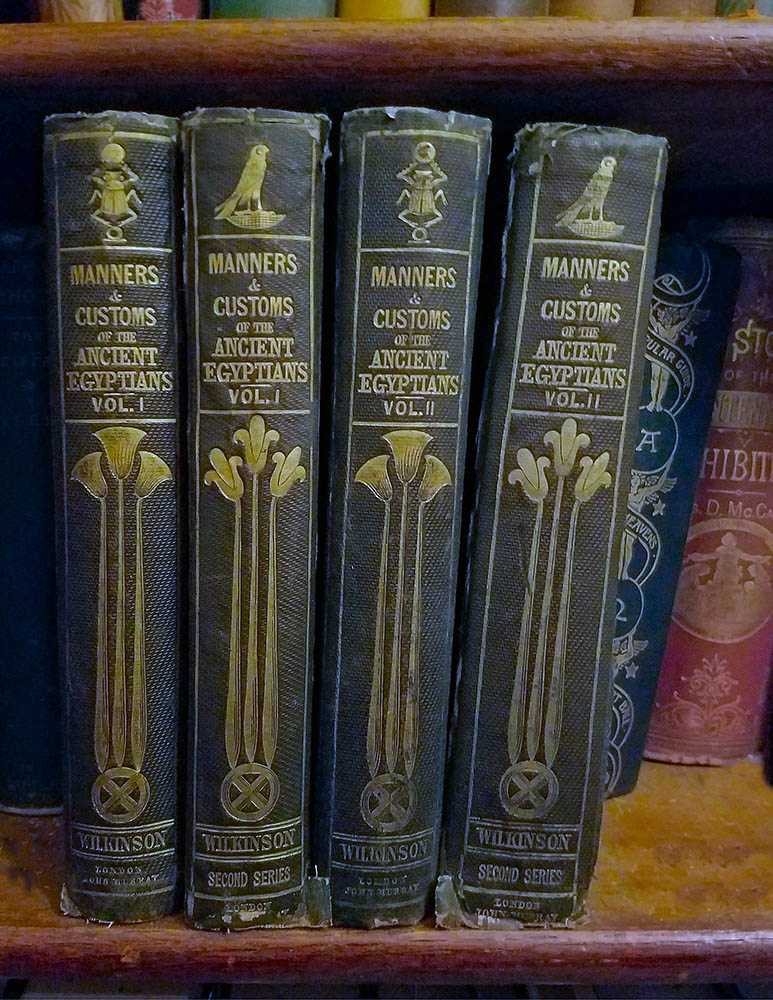

Of course, this ‘Scene in a Library’ was taken not within the confines of Lacock Abbey, but rather on Henry’s ‘peripatetic shelves‘ trundled into the sun out of doors. Talbot’s text accompanying this plate will be the subject of next week’s blog. Should you be visiting Lacock Abbey any time soon, it will be tempting to scan the bookshelves that line the hallways hoping to spot some of these very volumes. However, much of Talbot’s library was dispersed in sales in the early twentieth century and most of what now fills the shelves derives from remote family collections and various National Trust properties. Talbot’s three volumes of the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians are now in the Fox Talbot Archive in the Bodleian Library (lacking an image of these, I have photographed the slightly less pristine but more complete set on the shelves of Rock House).

Of course, this ‘Scene in a Library’ was taken not within the confines of Lacock Abbey, but rather on Henry’s ‘peripatetic shelves‘ trundled into the sun out of doors. Talbot’s text accompanying this plate will be the subject of next week’s blog. Should you be visiting Lacock Abbey any time soon, it will be tempting to scan the bookshelves that line the hallways hoping to spot some of these very volumes. However, much of Talbot’s library was dispersed in sales in the early twentieth century and most of what now fills the shelves derives from remote family collections and various National Trust properties. Talbot’s three volumes of the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians are now in the Fox Talbot Archive in the Bodleian Library (lacking an image of these, I have photographed the slightly less pristine but more complete set on the shelves of Rock House).Since we cannot re-create all of Talbot’s book holdings, instead let me turn to the observations of the great Parisian photohistorian and collector, André Jammes. He has a way of getting right to the root of an issue and conceived of the theory that this scene might might have been a self-portrait of the inventor. Jammes identified not only the three volumes of Wilkinson’s Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, but also Philological Essays, Miscellanies of Science, Botanische Schriften, La Storia Pittorica dell’Italia de Luigi Lanzi, the first three volumes of The Philosophical Magazine (its pages were rich with articles by Talbot), and three volumes of Thomas Gaisford’s edition of Poetæ Minores Græci (some years after this image was taken, Talbot’s beloved sister Horatia would marry Thomas Gaisford).

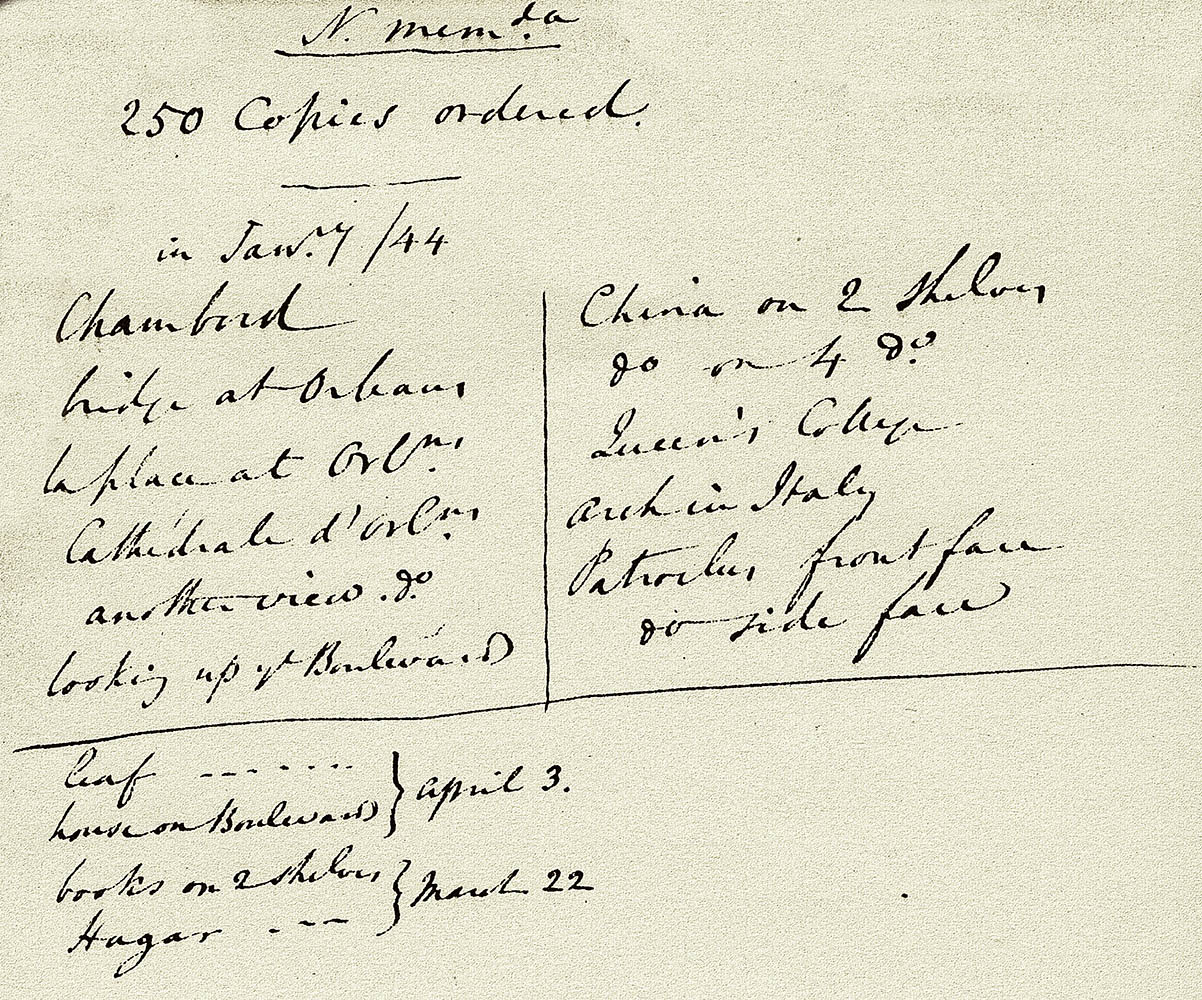

Although somebody (I am sure not Talbot, and probably not one of his contemporaries) scratched the number 8 into the waxed negative, there are no other inscriptions and little clue to its dating. The only bookend that we have for this is when Talbot placed the order with Nicolaas Henneman for 250 copies (the initial print run of The Pencil of Nature) on 22 March 1844; whether the negative was taken immediately before this or many months before may never be known.

How did the idea for the ‘Scene in a Library’ originate?

“Bookcase” in Lacock Abbey, 26 November 1839

“Bookcase” in Lacock Abbey, 26 November 1839

This is the earliest Talbot photograph of books that I know of – it is an extraordinarily ambitious effort, especially considering the context of when it had been taken. The year 1839 had been a horrible one for Talbot, first losing out to Daguerre, then being disappointed by ham-fisted handling of his invention by The Royal Society in London, all the time being frustrated by unusually poor weather that stole from him the very currency of photography, light. Perhaps this is also a self-portrait, a record of the emblems of the landed gentry, clocks and Dresden china and especially finely-bound books. Books neatly arranged, some in series, books whose spine labels promised windows into other worlds. Henry Talbot’s was in his element here. Even with the curtains drawn back to let in as much light as possible, the exposure in November must have been a long one, perhaps half an hour to an hour – the changing angles of sunlight during this softened the shadows, although a remarkable amount of detail is retained.

A few days later Talbot wrote to Sir John Herschel, enclosing “a little sketch of the interior of one of the rooms in this house, with a bust of Patroclus on a table.” He too-modestly felt that “there is not light enough for interiors at this season of the year, however I intend to try a few more. I find that a bookcase makes a very curious & characteristic picture: the different bindings of the books come out, & produce considerable illusion even with imperfect execution.”

Whereas the previous image seems highly personal to Henry himself, there are other views of the bookshelves in Lacock Abbey where his intent is more obscure. The music stand in this one would point towards his sister Horatia or his friend Amélina Petit, reinforced by the chinz chair favoured by the women of Lacock Abbey.

Just when did Talbot actually start concentrating on the books themselves as the subject, rather than a supporting element in a scene? His letter to Herschel indicates that he was aware of this potential early on. Frustratingly, although both the negative and this print survive, we have little clue as to when it was taken. Given its rough state and its inclusion of one of Talbot’s early albums, my feeling is that it was a preliminary attempt.

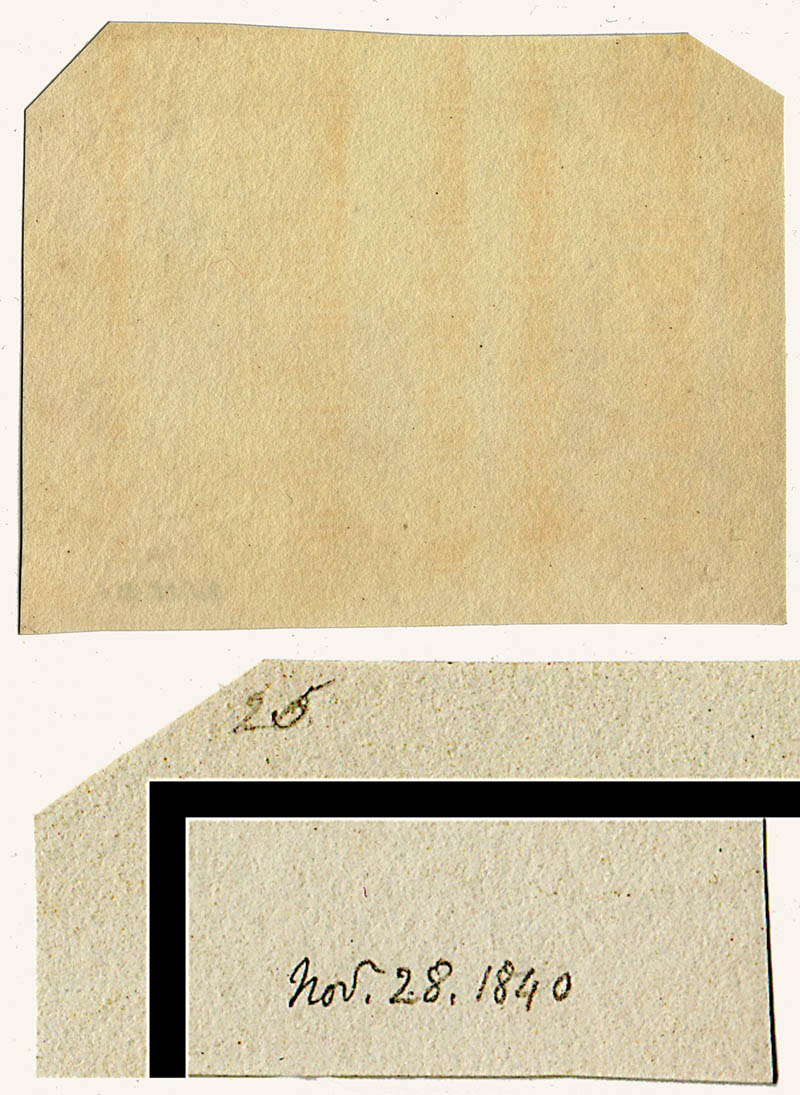

28 November 1840

28 November 1840

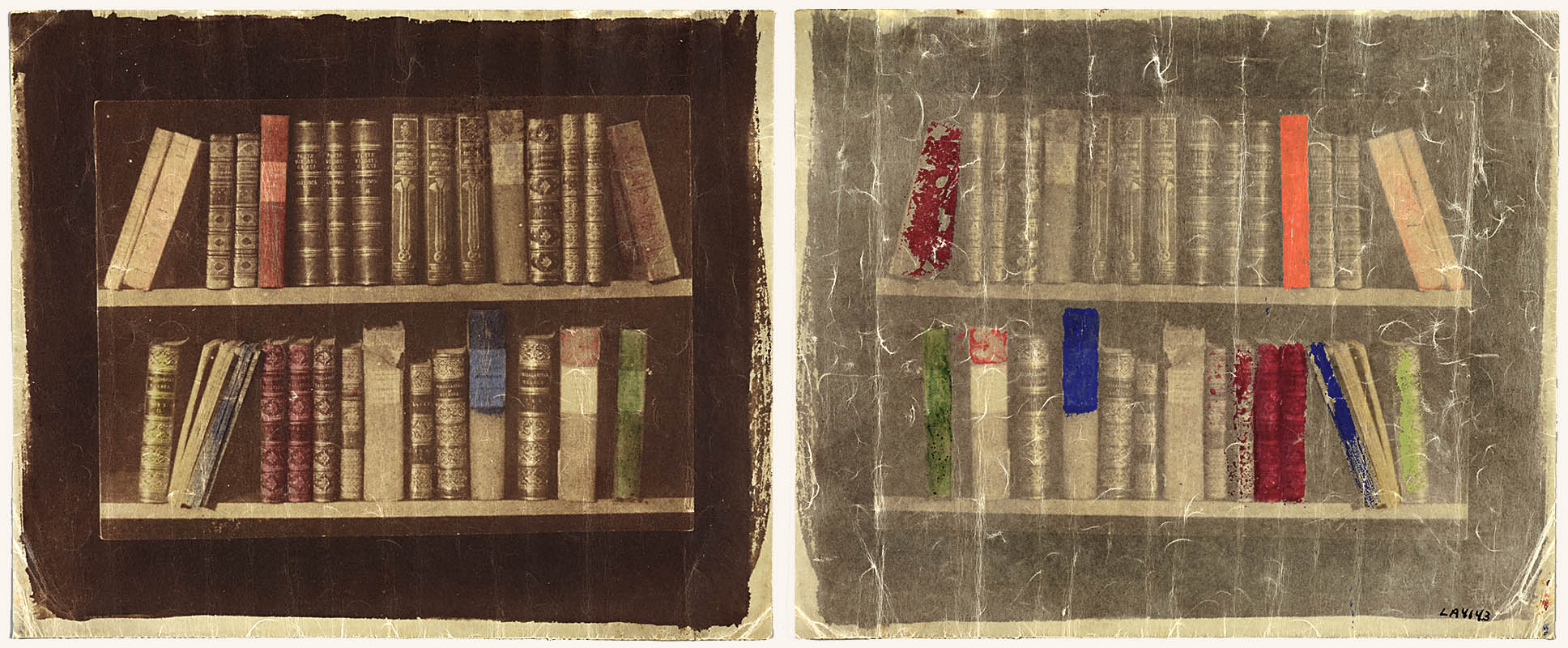

This highly detailed print was collected by Lady Elisabeth for one of her grand albums of her son’s photographs. Talbot’s photographic process has transformed hefty volumes into miniature books – a library that one could carry in the pocket. Was this the photograph that Lady Elisabeth referred to a fortnight before the issue of no. 2 of The Pencil of Nature? “I have been careful not to shew the Book scene which is in my Portfolio for fear they should be struck with its great superiority to the forthcoming ‘Scene in the Author’s Library’. ”

Fortunately for us, Talbot carefully dated this negative on the verso. That confirms that he had turned to his newly-discovered calotype process, enabling an exposure time even in a closeup of a matter of seconds rather than tens of minutes. Does the ’25’ represent the exposure time in seconds? More likely than a call for 25 prints.

Although only one negative is known for the published Scene in a Library, there is an interesting variant image that exists in two nearly identical negatives, one of which was severely trimmed. This negative is not as sharp as it should be, most likely from camera movement, yet it was waxed and trimmed and thus not rejected immediately. Perhaps Henry remained hopeful for a while that he could salvage it, perhaps a servant was preparing to print it without realising the defect.

Now, was this image intended as a self-portrait of Henry’s life? Disarray, elements missing, others crashing out of their careful organisation? Or was it a study of shapes and modulations of light?

recto/verso, waxed & coloured

recto/verso, waxed & coloured

Finally, just a reminder that all iterations of a unique image are gathered under one Schaaf number in the Catalogue Raisonné. In the case of ‘A Scene in a Library’, we have the original negative, many prints bound into copies of The Pencil of Nature. In addition, there are numerous loose prints, some untrimmed, and one that was printed before the negative was trimmed to its present size. There is also this oddity, a hand-coloured and waxed transparency. In 1841, Constance scolded her husband: “Those on the Shutter in Mlle Amélina’s room are all nearly destroyed by the Sunshine. This is a sad pity! you must really invent some other fixing process or some new fixing liquid.” By the time this was produced Talbot would have learned his lesson and avoided decorating the windows. I think it more likely that this was intended for some sort of ‘peep box’, trans-illuminated by a candle and entertaining in the parlour.

In any case, colour will be the basis of next week’s blog, which will follow more directly Talbot’s own thoughts on ‘A Scene in a Library.’

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • The Daily Telegraph, 27 September 1877, p. 5. • WHFT, A Scene in a Library, salted paper print from a calotype negative, prior to 22 March 1844, same as plate VIII in The Pencil of Nature, No. 2, published, 29 January 1845, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA8; Schaaf 18. • André Jammes, “A Scene in a Library,” Photographie, n. 1, Spring 1983, p. 50. • The listing is in WHFT’s notebook, Memoranda London, (May 1840 – April 1844), p. 78; Fox Talbot Collection, Manuscripts, The British Library, London. • WHFT, “Bookcase” at Lacock Abbey, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, 26 November 1839, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2005.100.629; Schaaf 2319. • Although Herschel’s print has not been located, this was probably WHFT’s view of Patroclus in the Window, photogenic drawing negative, 23 November 1839, National Science and Media Museum, 1937-1514; Schaaf 2317. It is illustrated in my Out of the Shadows; Herschel, Talbot, & the Invention of Photography (London: Yale University Press, 1992), plate 51. • WHFT, Bookshelves, Chinz Chair and Music Stand, paper negative and salted paper print (enhanced); negative courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York, print Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, LA2145; Schaaf 1188. • WHFT, Closeup of Bookshelves, salted paper print from a paper negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-365-25; Schaaf 3963. • WHFT, Study of Books, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 28 November 1840. Print in one of Lady Elisabeth Feilding’s albums in the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-366/110; negative in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995-206-51; Schaaf 2531. • WHFT, Tumbled Books on Two Shelves, calotype negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-4328; Schaaf 103. • WHFT, Tumbled Books on Four Shelves, salted paper print from a calotype negative, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA50; Schaaf 104. WHFT, A Scene in a Library, coloured and waxed salted paper print from a calotype negative, prior to 22 March 1844, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA4143; Schaaf 18.