In 2004, an era of relative tranquility when unsolicited emails were less common, I recoiled at the word ‘Law’ in the From line. Normally lawyer-averse, I was relieved to see that this came from a Harvard librarian in their Law School’s Special Collections. Mary Person had become intrigued by the signature on the flypage of one of their earliest law books and a web search had directed her to the Talbot Correspondence Project, at that point mid-way through its initial publication. Could there be a connection to Henry?

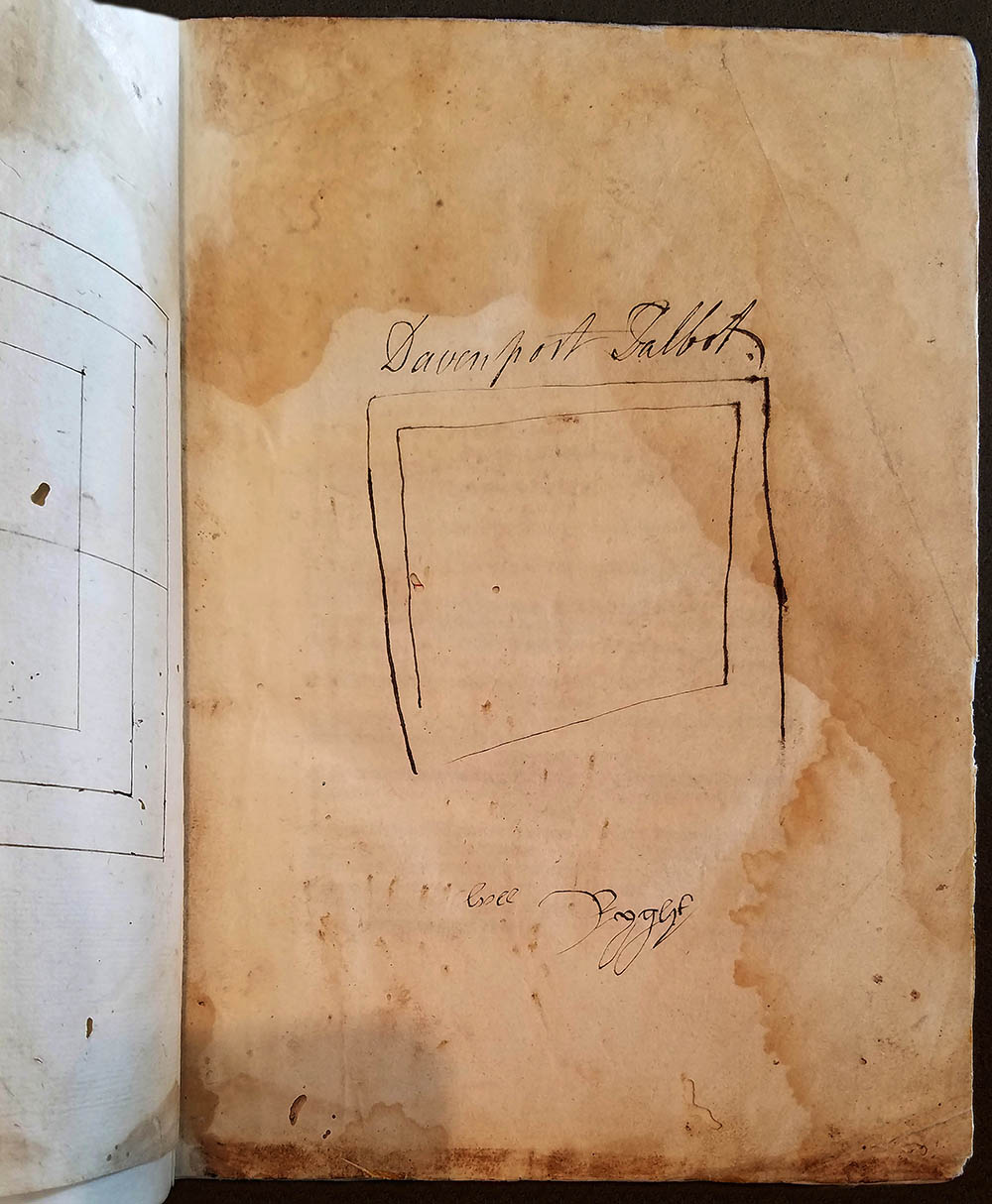

I was able to confirm that William Davenport Talbot (1764-1800) was indeed the father of Henry. Born a Davenport, upon the death of his mother in 1788 he changed his name to Talbot. A ‘gay blade’ in the parlance of the day, William left Oxford’s Christ Church College without a degree and was on active duty in the 88th Foot until shortly before he died. He had married Lady Elisabeth Fox Strangways in 1796, a blissful marriage cut short by his death in 1800 just a few months after the birth of his son Henry.

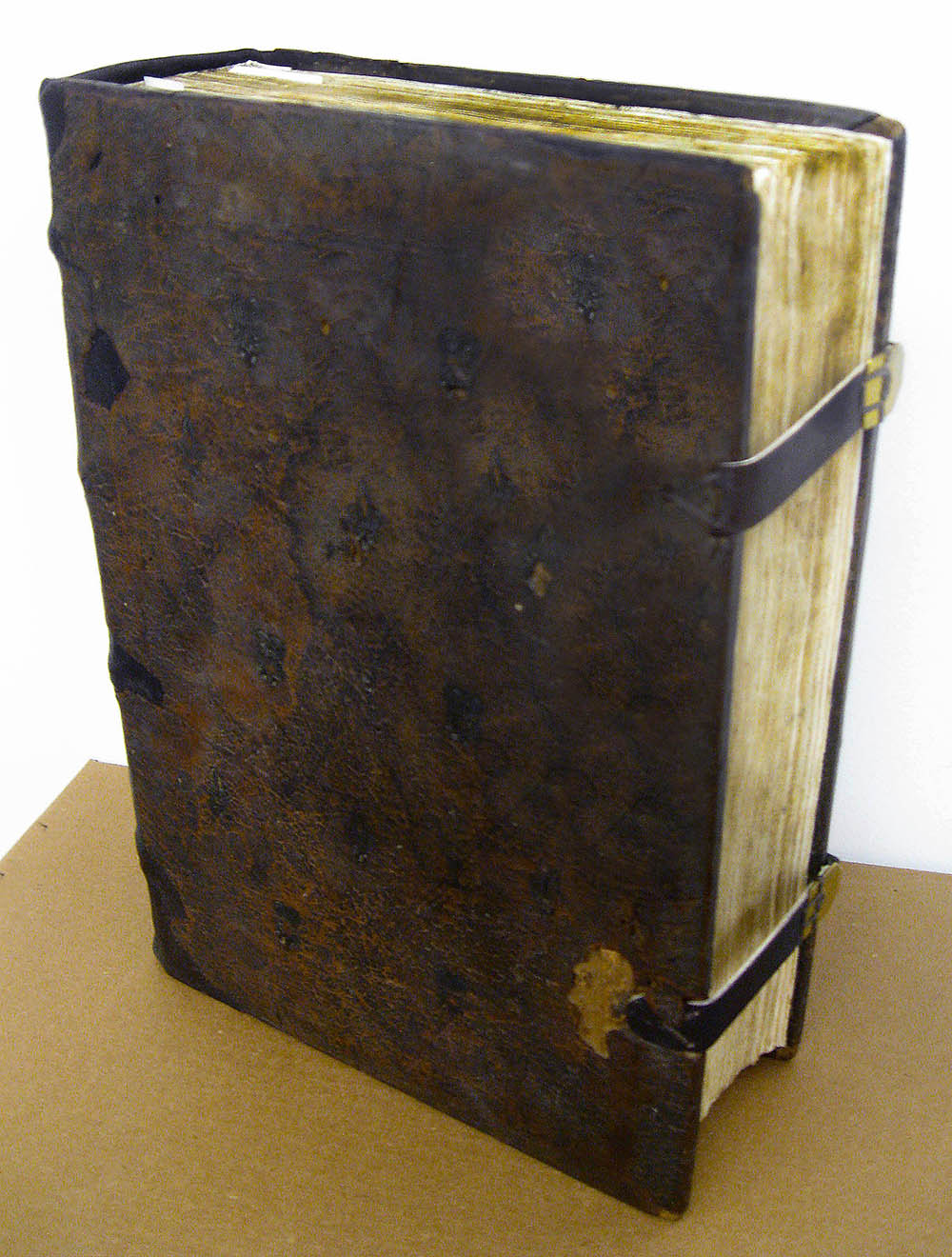

More out of curiosity than of hope, I enquired about the volume and Ms Person immediately arrested my attention when she reported that it was Nova Statuta, an 1484 treatise on taxes and penalties. I asked her to go to the end of Chapter 19, but she soon replied with some sadness that the last page of that chapter had been excised.

Great! I replied (in retrospect, perhaps not the word of sympathy that she was expecting)

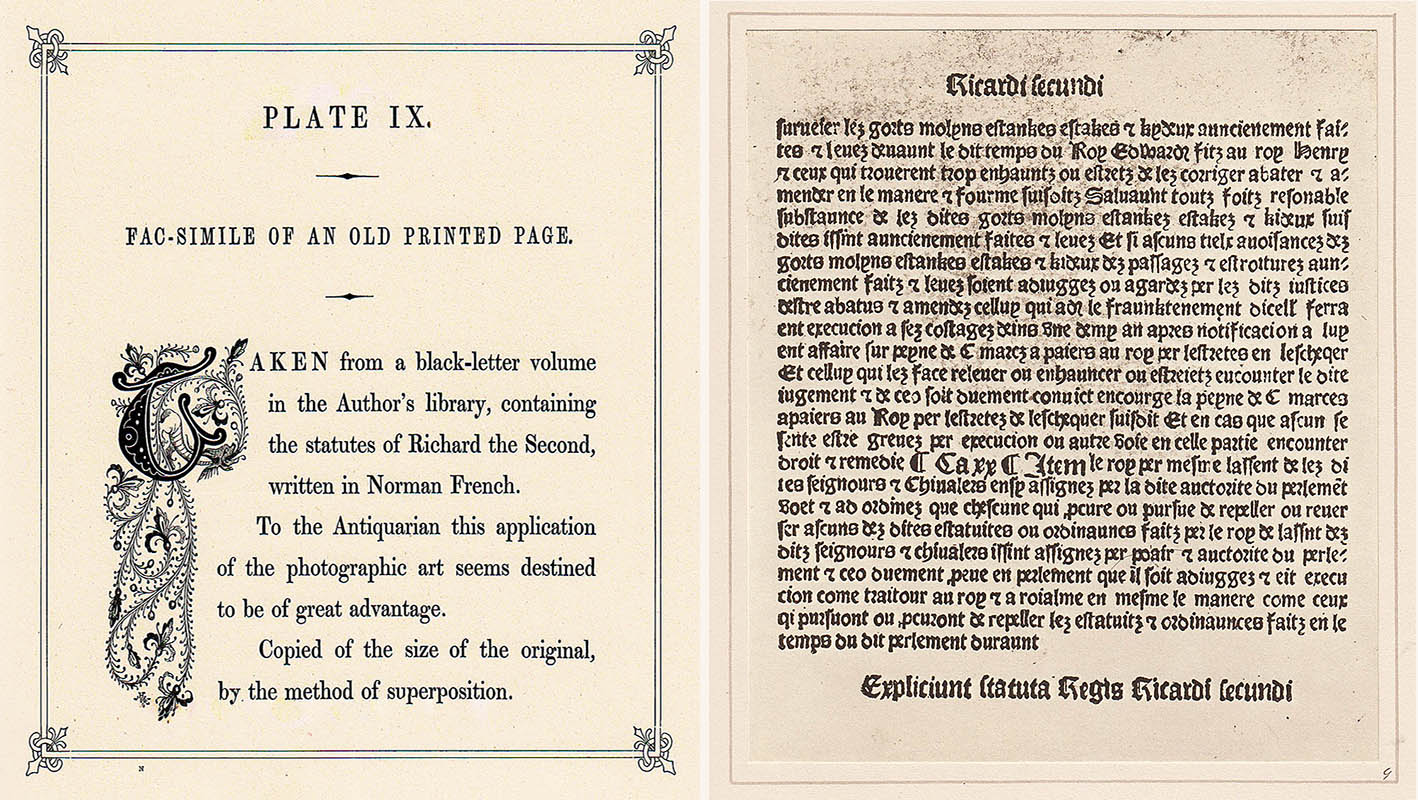

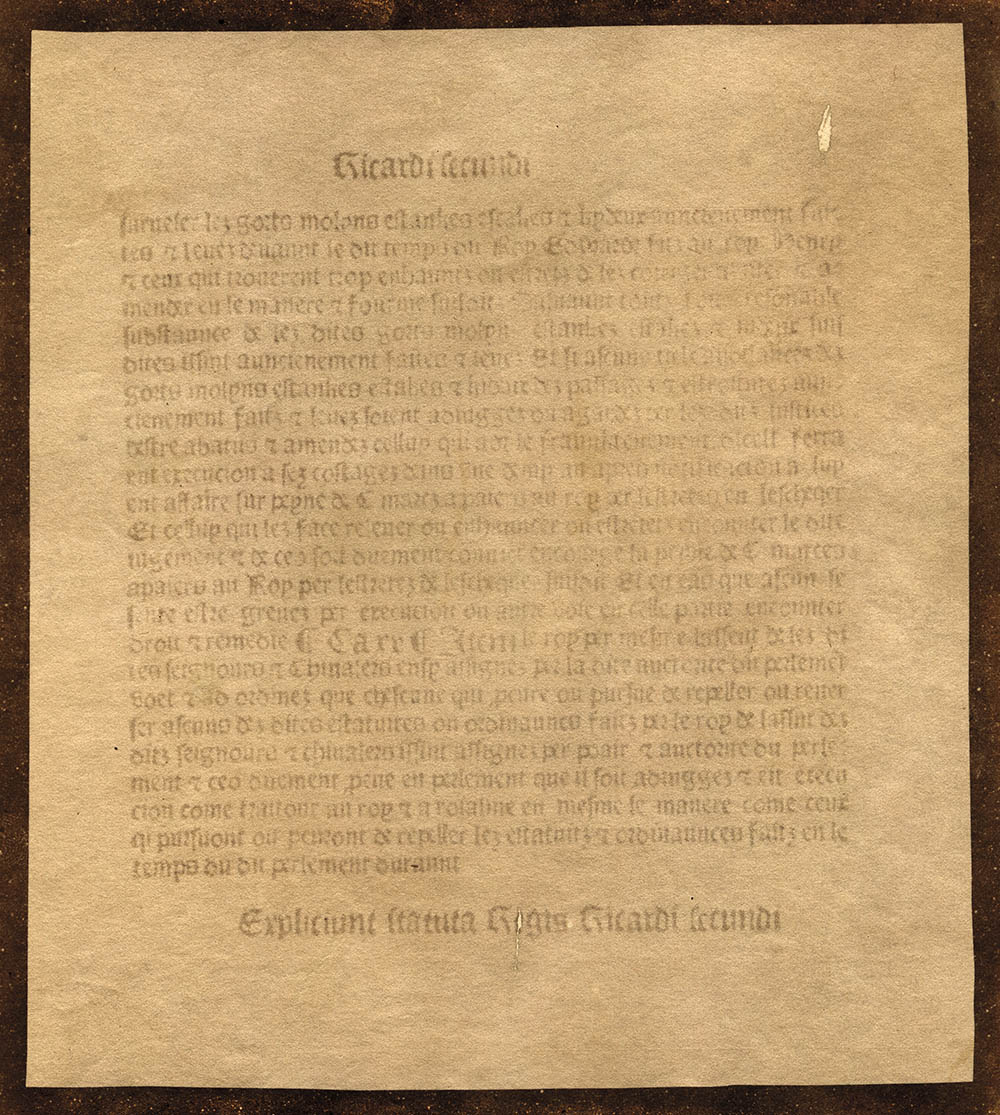

Plate 9 in The Pencil of Nature was an exact photographic copy of a leaf from “a black-letter volume in the Author’s library,” namely the copy of Nova Statuta that had belonged to his father. Talbot explained that the page was “copied of the size of the original, by the method of superposition,” in other words, by contact printing the sheet onto sensitised photogenic drawing paper. The resulting negative could then be printed the 250 times he expected that he would need for The Pencil of Nature. Now, this approach presents a problem, for if the original was printed on both sides of the paper, as would be typical, the opposing type would show through. When the adventurous Amelia Guppy set about copying some of Sir Thomas Phillipps’s manuscripts, she laboriously retouched the negatives to eliminate the shadows of the spurious type. Talbot cheated a bit by selecting a page ending a chapter, a page printed on one side only. Long ago I had examined another copy of Nova Statuta in the Morgan Library and had confirmed that Talbot’s copy had to have been made by direct contact.

The Athenæum immediately caught him out. Referring to Talbot’s claim about the great advantage to the antiquarian, their reviewer pointed out that “this would have been more apparent, if this black letter page had been copied by the camera, instead of by superposition. That this might have been done, is evident from the manner in which the titles of the books in plate 8 have been copied. Otherwise than by the camera, it would be impracticable to copy a page which is printed also on the back—nor could we by superposition copy any manuscripts on vellum or papyrus.”

In 1845, the reviewer’s comment was both perceptive and fair. The calotype enabled camera views taken by reflected light, as we have seen in plate 8, A Scene in a Library. However, Talbot had become interested in copying this book in 1839 at a time when only photogenic drawing was available to him. While the negative may or may not have survived (more on that in a moment), there are at least four prints extant that we know were made in 1839.

These 1839 prints can be identified by the distinctive irregular outline of their shared photographic negative. This one in the Bodleian was inscribed by Talbot “Nov. 12”; the print in the Harrison D. Horblit Collection is inscribed “Novr. 12/39” and one from Harold White’s collection is inscribed “Nov./39”. There are at least nine surviving variants of this image, represented by eight negatives (some with prints) and the above group. Since the above was made from the largest negative trim it is impossible to determine if these were printed from one of the surviving negatives before it was cut down. It is equally difficult to determine which negative or negatives were employed in printing for The Pencil. Once the edges of the prints were trimmed for mounting, the interiors lack distinctive features. Given that so many virtually identical negatives survive, it is quite possible that Henneman put a number of them into service at once, gang-printing this particular plate.

The Fac-simile of an Old Printed Page was published in Part Two of The Pencil of Nature, issued on 29 January 1845. In addition to the 12 November 1839 prints, one negative is dated 23 August 1841, and there are a couple of interesting experiments that were enclosed in a packet dated 8 April 1843.

Just what the goal of these experiments was is somewhat uncertain. Frustratingly, Talbot’s Notebook Q ends on 5 April 1843. Numerous loose notes survive for the period but they jump from 6 April to 10 April, all on the same large sheet of paper so apparently nothing is missing. On 6 April Talbot was experimenting with a ‘rapid memorandum paper’ and recorded that ten minutes in the sun “seems too long for Ricardi Secundi” but that the same amount of time in “evening skylight seems about right.”

Just what the goal of these experiments was is somewhat uncertain. Frustratingly, Talbot’s Notebook Q ends on 5 April 1843. Numerous loose notes survive for the period but they jump from 6 April to 10 April, all on the same large sheet of paper so apparently nothing is missing. On 6 April Talbot was experimenting with a ‘rapid memorandum paper’ and recorded that ten minutes in the sun “seems too long for Ricardi Secundi” but that the same amount of time in “evening skylight seems about right.”

That fancy scrolled ‘L’ [?] appears on a number of Talbot documents and photographs but I have no idea what it means – any suggestions welcomed.

That fancy scrolled ‘L’ [?] appears on a number of Talbot documents and photographs but I have no idea what it means – any suggestions welcomed.

Talbot included a copy of An Old Printed Page in the album that he exhibited at the pioneering 1852 exhibition at the Royal Society of Arts in London, so his interest in this copy started in 1839 and was maintained for more than a decade.

But we must return to Mary Person’s discovery at Harvard. Unfortunately the travels that this volume took between the shelves of Lacock Abbey and its arrival at the Law School in the early 20th century are unknown. There were numerous book sales and auctions from the Lacock Abbey library, especially around that time, so it may have been acquired by an interested party or may have simply worked its way through the book trade. In any case, it was in severely degraded condition by the time that it came to her attention (the binding has since been masterfully restored).

In pulling together the pieces, Ms Person made a wonderful discovery. Miraculously, the cut-out piece of text survived all these travels simply tucked into the volume. Even more amazing to me, a small note in the distinctive handwriting of Talbot’s son, Charles Henry, accompanied it. He had discovered the scrap in 1897, immediately recognised its one-time use as a ‘photographic object’ and speculated on whether it could be restored in the volume. A restoration binder would probably have tried to remove the wax or oil permeating the page, but fortunately, Charles Henry had inherited his father’s propensity for procrastination. The ‘photographic object’ survived intact, in exactly the same state as when his father used it to produce photographic negatives that in turn could be multiplied through prints.

There are a couple of other mysterious aspects to this volume. The inscription page also has a strange rough sketch, suggesting the rectangular area that might be used as the ‘photographic object’.

But the page opposite is even more intriguing. It has three carefully drawn rectangles nestled within one another. Did Henry recognise the unsteadiness of a knife in his own hands and give instructions to somebody else to excise and trim the printed page? I’m not really satisfied with that explanation but cannot at this time come up with a better one. Mary Person wryly observed that this was “certainly an unusual ‘doodle’ in such a book”.

The ‘photographic object’ had its public debut in 2007 in an exhibition at Hans P Kraus’s gallery in New York: William Henry Fox Talbot, Selections from a Private Collection. In 2012, the volume and its contents were featured in an exhibition at Harvard, Provenance Detectives: Revealing the History of Six Library Artifacts.

While it often seems that the gods were cruel to Henry Talbot in his photographic days, it is extraordinary that some guardian angel safeguarded the little square of waxed text and its explanatory note over many decades through several hands and many thousands of miles of travel. It emphasises once again the international nature of Talbot’s legacy – a bounty that we hope we are extending and preserving through the Catalogue Raisonné.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Nova Statuta. (London: printed by William de Machlinia, 1484), STC 9264 Beale S1; Harvard Law School Library. The page Talbot employed was at the end of Chapter 19. • For more on the wonderfully eccentric Amelia Guppy’s dedicated work see my “ ‘Splendid Calotypes’: Henry Talbot, Amelia Guppy, Sir Thomas Phillipps, and Photographs on Paper,” in Six Exposures: Essays in Celebration of the Opening of the Harrison D. Horblit Collection of Early Photography (Cambridge: Houghton Library, Harvard University, 1999), pp. 21-46. • Athenæum, no. 904, 22 February 1845, p. 202. • WHFT, Fac-simile of an Old Printed Page, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, John Dillwyn Llewelyn Collection, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford; Schaaf 4160. • WHFT, Variations on the Fac-simile of an Old Printed Page, experimental paper negatives, 8 April 1843, extracted from a dated folder; Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London; Schaaf 4375 and Schaaf 4376. • WHFT’s April 1843 notes are in the Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London, LA43-46. The notebooks immediately preceding this have been published in facsimile by me: Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks ‘P’ & ‘Q’ (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). • Harvard’s waxed page and a splendid print derived from it (Schaaf 851) were illustrated in my Sun Pictures Catalogue Seventeen: William Henry Fox Talbot, Selections from a Private Collection (New York: Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, 2007), pp. 14-15.