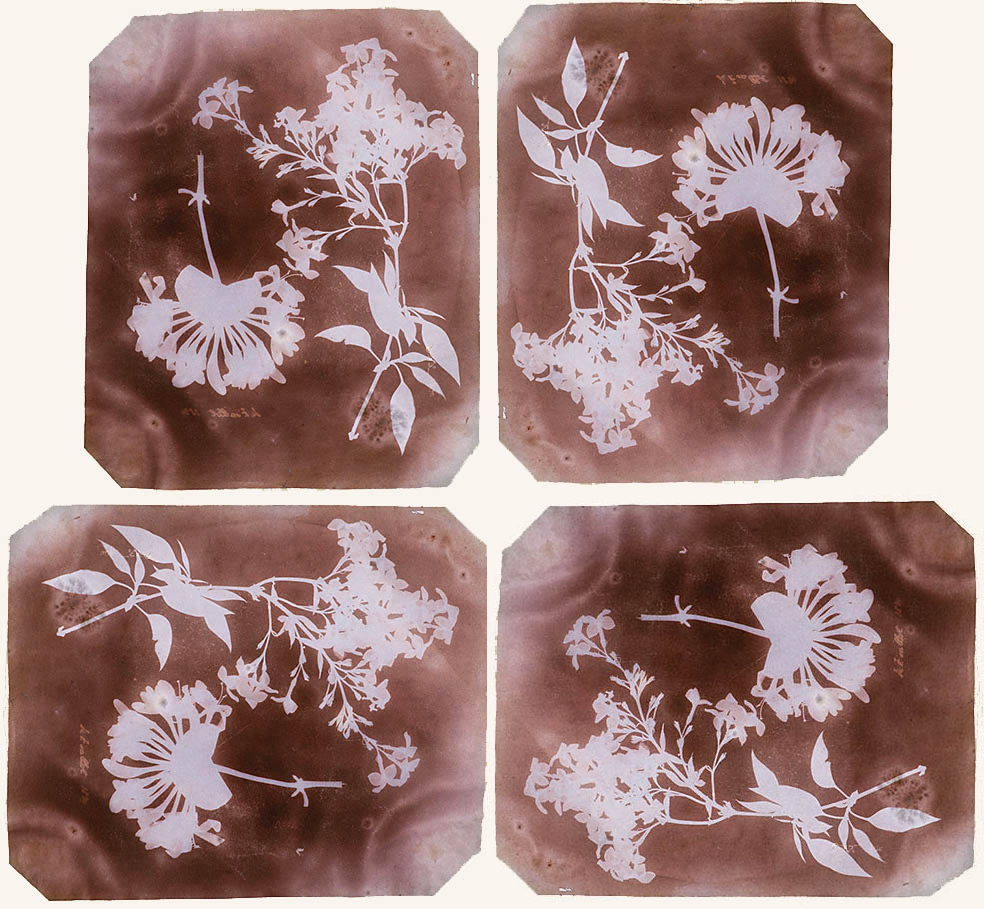

What is the ‘correct’ way to orient a Talbot image? If you were hanging this 1839 photogenic drawing negative, which way would you prefer? Or if this was a quiz, what clue do you have to guide you to the correct answer? (the ‘H. F. Talbot 1839’ inscription just showing through below one plant implies how Henry thought about it, so the upper left is probably the best choice). When the subject of a photograph is architecture or a portrait, the orientation is usually obvious. In those cases where the ‘right side up’ is more ambiguous, sometimes there are clues within the image itself.

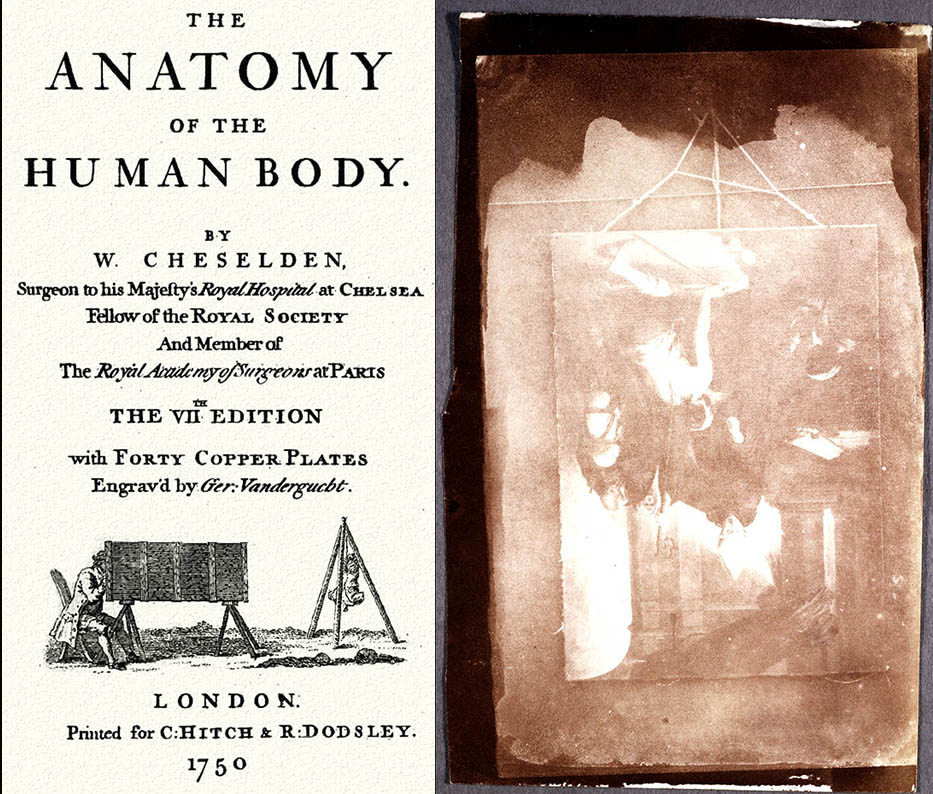

It was probably Nicolaas Henneman who copied this print – in any case the elaborate and distracting background inexplicably turns up in a number of such images. Wallpaper? A convenient chair? The wooden wedges pinning the original in place were probably not the most gentle of means of attaching the print so we can probably assume that the subject was a commonly available commercial item. But at least the evidence is here as to how the photographer flattened it.

By the way, do any of you proper Art Historians recognise the original here, apparently a priest offering communion? We would like to add that to the record.

Anyone who has used a view camera is aware that a lens naturally inverts an image (for experience-deprived digital photographers you will just have to hold an old fashioned magnifying glass at arm’s length to prove the effect). Artists accepted this optical effect long before the advent of photography and here we can see William Cheselden’s illustrator drawing a torso in 1750 – a torso suspended upside down so that the image projected onto the ground glass of the camera obscura appeared properly to the artist.

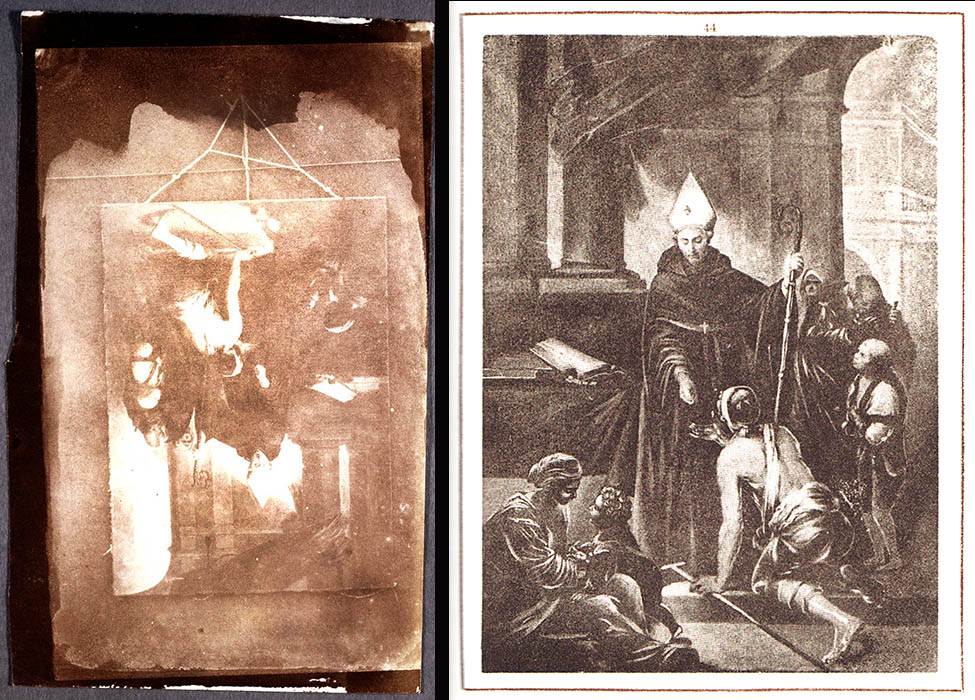

Presumably for the same reason – comfort in viewing – Nicolaas Henneman hung Murillo’s 17th c. St Thomas of Villanueva upside down while photographing it. A brace of surviving untrimmed prints betrays his working method. By the time the prints were trimmed and mounted in Stirling Maxwell’s Annals of the Artists of Spain there was no hint of the deception (nor of the fact that he copied a smaller 19th c. copy in oils by Roldan to stand in for the original).

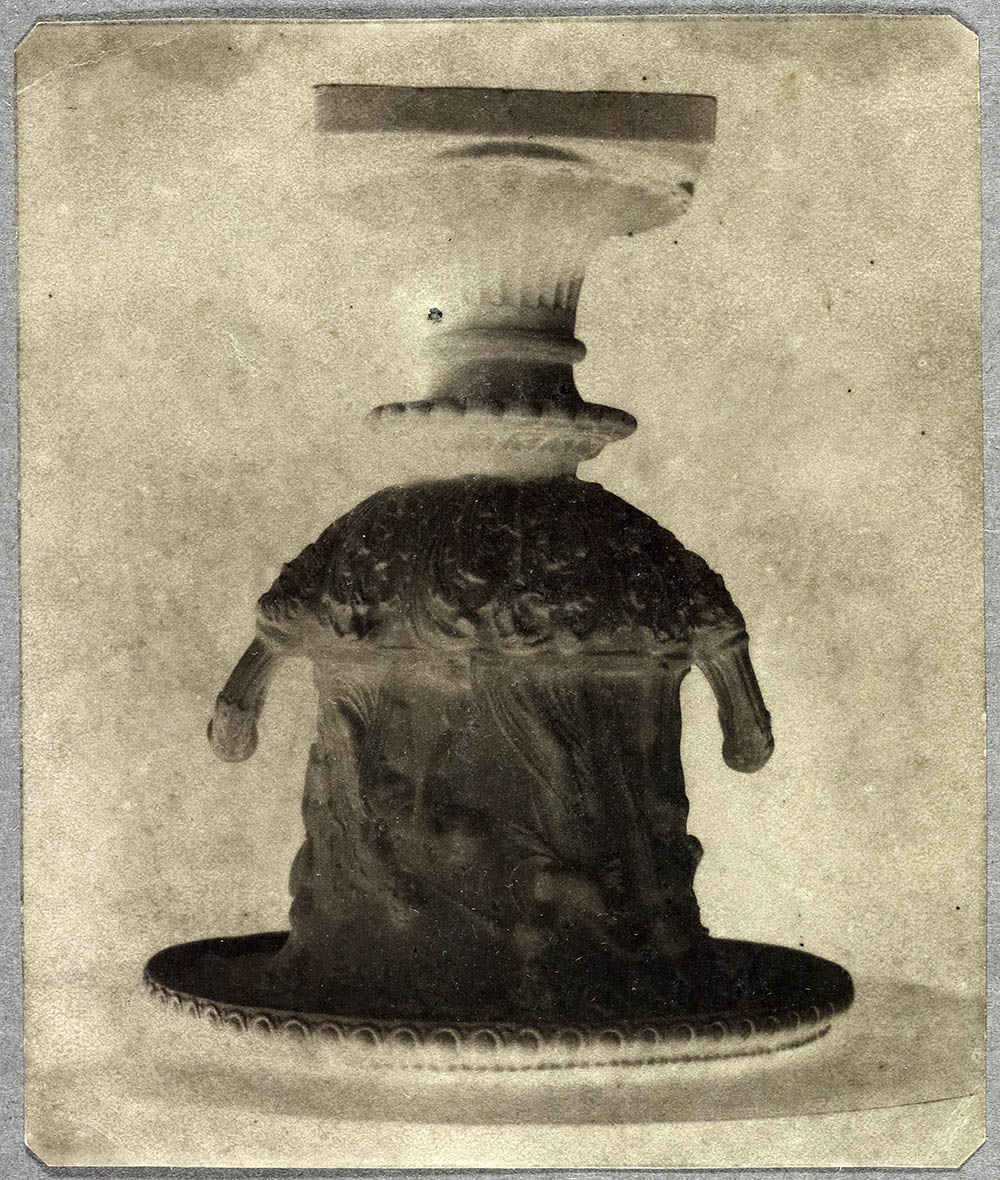

But was it always a small round table? As a woodworker, I notice that this one appears to be three-legged and it is possible that the disk is chamfered underneath, making the top thicker than it appears. The thickness of the legs is indistinct. Could it have been a milking stool?

In any case, this table or stool was perhaps not the best choice as it would have tipped over quite easily. Was that what prompted Talbot’s mother, Lady Elisabeth, to angrily enter into her diary: “Henry broke the bust of Clytie, which I have had for 43 years!”

A better image of the Laocoon above is needed for study. According to the metadata and cross-referencing with my diary, I took this snapshot at Photo London on 18 May 2005 – the small photograph was bound into an 1846 volume of the Art-Union . I have lost track of my note as to who was flogging it. If anybody knows of the present whereabouts of this I would be most happy to hear from them.

There were no established rules guiding Talbot’s photography – after all he had just invented the art – so he practiced a logical following of Nature’s rules. The milk glass vessel on the left took well to the overhead lighting of the sun. But what about the larger garden urn on the right? Its overhang would have shadowed the figures.

So Talbot did what was most logical for the subject. He inverted the urn and placed it on a tabletop, thus allowing the overhead sunlight to reach the critical details under the lip.

However strange, one can see how effective this approach could be. But did Henry expect ordinary people to do what the camera had accustomed him to do, to be able to look at a subject upside down?

The most definitive answer we can give to this question is the evidence of how he (or his family members) mounted the subsequent prints in their personal albums. Returning to the urn to the right of the milk glass, this was a gift to his Italian botanist friend, Professor Antoino Bertoloni. The inscription on the verso would have guided his friend to view the urn oriented as it would normally have been in the real world. But the inscription itself was slightly deceptive: “Urne éclairée d’en bas / H.F.T. 1840”, ie, ‘urn illuminated from below’.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Pair of Plant Specimens, photogenic drawing negative, 1839, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1972.325; Schaaf 4618. • Attributed to Nicolaas Henneman, Copy of a print of a priest, pinned against an elaborate background, salted paper print from a calotype negative, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-3210/3; Schaaf 4208. • William Cheselden, title page from The Anatomy of the Human Body , 1750. • Nicolaas Henneman, Copy of a Roldan oil copy of Bartolomé-Esteban Murillo’s St Thomas of Villanueva, salted paper print from a calotype negative, NSMeM, 1937-3430/2; Schaaf 5463. • WHFT, Statuette of Venus, on a Table, salted paper print from a calotype negative, William Talbott Hillman Collection, Schaaf 212. WHFT, Statuette of The Rape of the Sabines, on a Table, salted paper print from a calotype negative, NSMeM 1937-2680, Schaaf 1812. • WHFT, Statuette of The Laocoon on a three-legged table, salted paper print from a calotype negative, in a bound volume of the Art-Union for 1846, present owner unknown; Schaaf 1800. • WHFT, Milk Glass? Urn on a tabletop, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 19 April 1841, NSMeM, 1937-368-27, Schaaf 4978. WHFT, Garden Urn Taken Upside Down, salted paper print (enhanced) from a photogenic drawing negative, 1840, Bertoloni Collection, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena; Schaaf 4504. • WHFT, Garden Urn Taken Upside Down, paper negative, NSMeM, 1937-4340; Schaaf 907. • WHFT, Garden Urn Taken Upside Down, salted paper print from a paper negative, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London; Schaaf 5463. • WHFT, Garden Urn Taken Upside Down, salted paper print from a photogenic drawing negative, 1840, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London; Schaaf 4504.