Instead of starting 2018 with laments, I would rather briefly celebrate the lives well spent of two photohistorians who were friends and who had very different but dramatic effects on my Talbot studies. Both were swept away late last year by illness, long before their time.

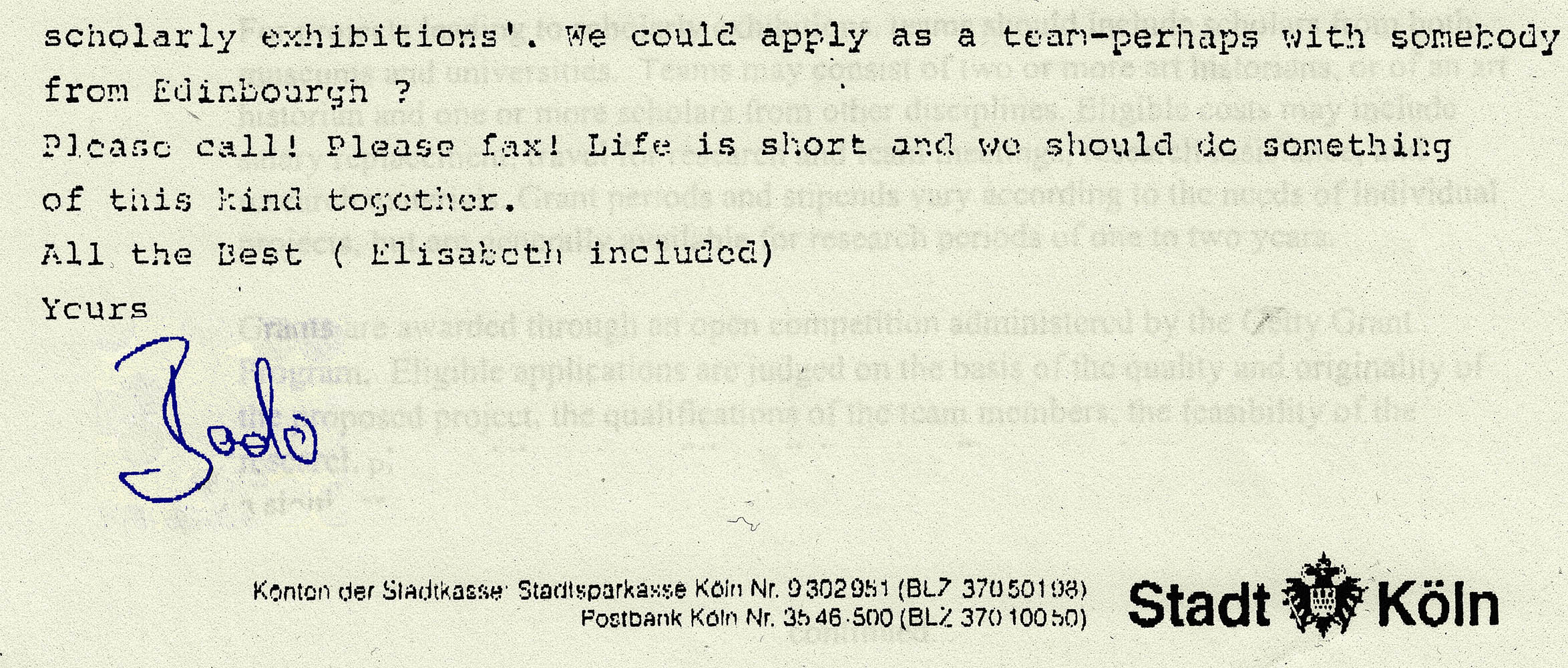

Dr Bodo-Balthasar von Dewitz passed away on 17 November. Bodo and I always joked that he must have been my younger brother, having been accidentally separated at birth, but in truth he clearly had noble blood. In an interview a few years ago he touched on one of our favorite topics – boring academics – his response was that in addition to being a respectable scholar “I’m also a very playful dog” – adding that research and exhibitions “must be fun too.” Bodo had been given a bottle of red wine on his 21st birthday (1971) and when I stayed with him and Annette in Bad Godesberg he always teased me with it – he didn’t drink red wine himself, but he would bring it out for display and remained unopened (and perhaps does so to this day). In 1985, Bodo received the first PhD granted in Germany for a historian of photography. After a brief flirtation with the commerce of art, he secured a museum position in Hamburg and then went on to the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, working with the Fritz Gruber collection. When Bodo was five years old in 1955, Agfa had purchased the photohistorian Erich Stenger’s collection for their factory museum. In 1974 they put it on loan to Cologne; Bodo became its curator and made very good use of it in numerous exhibitions and books. After two decades, with fortunes changing in the photographic industry, he suddenly found himself in a battle to keep it from being broken up and sold. It was through Bodo’s efforts that in 2005 it was declared a national treasure and acquired by the Museum. With my zero blog budget, I could not secure permission to publish what I consider to be the most typical portraits of him but you can view them yourself here. Bodo was always brimming with new ideas and unbridled enthusiasm and very kindly incorporated my texts in some of his numerous books. This 1997 message was a typical one from him – I am sure that several of our readers have similar ones:

Here is a downloadable pdf translation from the German of an excellent and wide-ranging 2011 interview of Bodo.

Here is the picture and description that he chose himself for our Research Associates page: Gavin Stamp, the noted architectural historian, is an independent scholar and honorary professor at the Universities of both Glasgow and Cambridge. He taught for a decade at the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the Glasgow School of Art. He has long had an interest in early photography, considering its potential for architectural history ridiculously under-exploited. His book, The Changing Metropolis (1984) illustrated many of the earliest photographs of London and was one of the first to highlight Talbot’s contributions to recording the built environment. Other of his books include studies of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Robert Weir Schultz and members of the Gilbert Scott dynasty. More recently he published The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme and Gothic for the Steam Age: An Illustrated Biography of George Gilbert Scott.

Here is the picture and description that he chose himself for our Research Associates page: Gavin Stamp, the noted architectural historian, is an independent scholar and honorary professor at the Universities of both Glasgow and Cambridge. He taught for a decade at the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the Glasgow School of Art. He has long had an interest in early photography, considering its potential for architectural history ridiculously under-exploited. His book, The Changing Metropolis (1984) illustrated many of the earliest photographs of London and was one of the first to highlight Talbot’s contributions to recording the built environment. Other of his books include studies of the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson, Robert Weir Schultz and members of the Gilbert Scott dynasty. More recently he published The Memorial to the Missing of the Somme and Gothic for the Steam Age: An Illustrated Biography of George Gilbert Scott.I’m afraid that gives little sense of Gavin’s lively personality and his willingness to plunge into the battle to fight the good fight. I first met him through the pages of The Changing Metropolis, where he placed some of Talbot’s early architectural photographs into the mainstream of the visual record of the evolution of London. We toyed with the idea of an expanded Talbot’s Metropolis but never got around to doing it. Intellectually serious on stage or on the screen, Bohemian in his character otherwise, Gavin proudly identified himself as an independent scholar. However, his stint as a professor at the Mackintosh School of Art in Glasgow left its imprint on many there. Gavin was always a passionate defender of proper architecture and I am sure that both the Victorian Society and The Twentieth Century Society will miss him immensely. The Telegraph published an insightful obituary (downloadable pdf) written I know not by whom, but obviously by someone very familiar.

I must admit that I had never heard of a Bomb Cyclone and in this era of ‘fake news’ at first I thought it was journalistic sensationalism. But here at Rock House in Baltimore, Herschel, our Russian Wolfhound, is presently far happier than our Southern-born cat, Claudet. Virtually all of the East Coast of the US is under frigid temperatures and much of it covered in snow. I’ve even heard whimpering from our Oxford base about the cold weather. In spite of one politician’s brilliant fancy that perhaps a bit of global warming would be a good thing, from time to time anomalous weather conditions affected Henry Talbot just as much as they do to us today. Perhaps feeling a bit of cabin fever, if not a challenge, on 12 January 1841 Henry Talbot placed a sheet of his newly-discovered calotype negative paper in his larger camera. Avoiding the chill outside, he pointed his lens out one of the Oriel windows on the south front, towards the southeast Ha-Ha. Perhaps he was tempted by the light reflecting off the deep snow, maybe the River Avon flooding the lawn attracted him, but the overall conditions must have been challenging at best.

calotype negative and digital print

The negative is now so faint that I could barely pull a digital print from it, but for those who have visited Lacock Abbey, the wall should be clearly recognisable. Darran Green remembered this elevated point of view from his period of residence in the Abbey some three decades ago, and Roger Watson, Curator of the Fox Talbot Museum confirmed it with his snapshot.

Since Talbot’s negative was very early in the life of the (as yet unnamed) calotype process, he dated it on the verso, boldly enough to reveal itself in any print:

Initially the negative must have been strong, for three prints from it are known to survive, two of them with 1840 watermarks. One was sent to his friend, Sir John Herschel, inscribed on the verso “Country Covered with Snow – Winter of 1840-41.”

Initially the negative must have been strong, for three prints from it are known to survive, two of them with 1840 watermarks. One was sent to his friend, Sir John Herschel, inscribed on the verso “Country Covered with Snow – Winter of 1840-41.”

The day before this was taken, Talbot’s father-in-law William Mundy wrote from Markeaton “How do you all bear this severe weather?” The Morning Post observed that the thermometer in the Zoological Gardens in London stood at zero and I imagine that the countryside in Wiltshire was even colder. Talbot took his photograph on Monday, but on the previous day a “very heavy fall of snow” had deposited up to a foot in London.

Unfortunately we have only very skeletal information about what Henry was up to that winter. In one of his journals he noted that on 9 January there was “much snow at night very severe weather lately” and that 15 January there was still “very deep snow.” However, six days after his negative was taken, Talbot recorded a “Rapid thaw. Very high flood – Snow all gone.” The River Avon, flowing past the Eastern side of Lacock Abbey, frequently flooded the fields, sometimes nearly reaching the building.

In spite of the paucity of detailed records, it is clear that Talbot was unusually active photographically during this winter period. Starting on 2 January he recorded a string of notes very briefly outlining the ideas that he was conceiving and testing. In the period up to 16 February, Talbot experimented with thicker paper, his Waterloo process, mixing gold into his gallic acid and several other approaches. Perhaps someday we will be able to associate some of the hundreds of scraps of paper with these experiments. So far we have traced ten distinct images positively dated to the month of January in 1841, including the first known iteration of The Open Door, the 21 January 1841 Soliloquy of the Broom.

For those sad souls who do not like snow, I’ll wish you a “rapid thaw” with the “snow all gone.” And I hope that the warmth of my new year’s greetings helps to offset the present temperatures.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Thanks to Darran Green for identifying from memory the point of view, and to Roger Watson for confirming it on site. • WHFT, Country Covered with Snow, calotype negative, 11 January 1841. Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.0206.1; Schaaf 2545. • WHFT, Country Covered with Snow, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 11 January 1841. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Eo56-15; Schaaf 2545.