I am delighted that the ever-productive sleuth Rose Teanby returns with another in her series of examinations of Talbot’s photographic responses to the industrialising world around him.

But first, we need to celebrate a double birthday that occurred this week, on Wednesday 7 March.

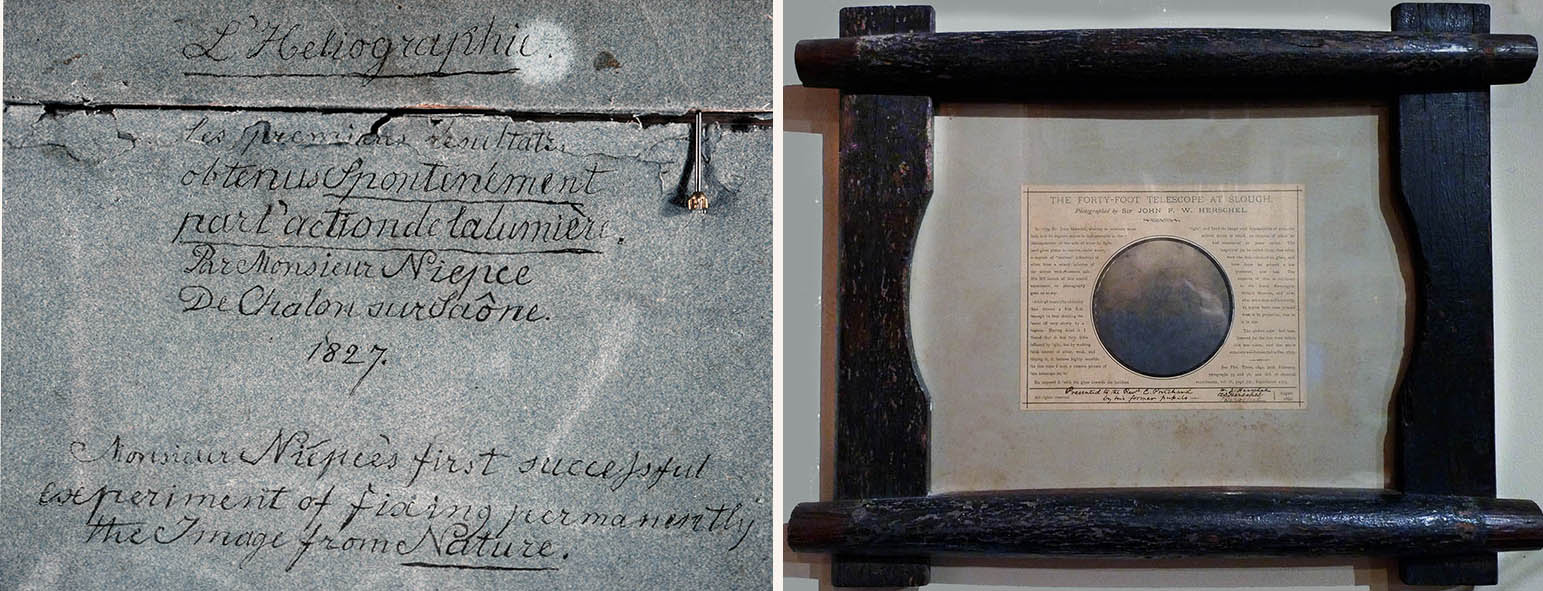

I am happy to recognise Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (7 March 1765 – 5 July 1833) as the father of modern photography – and just perhaps of photomechanical printing as well. What is undoubtedly true, as bolstered by the evidence of Franz Bauer, is that Niépce was able to bring in-camera and permanent photographic images to Britain in 1827. My long-held opinion is that this plate, the pride of the Helmut & Alison Gernsheim Collection in Austin, was intended by Niépce more as a photolithographic plate than as a wall display image, but that is a discussion that we shall save for later. Also born on this day was Talbot’s close friend and collaborator, Sir John Frederick William Herschel (7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871). Just in photography alone, we owe so much to Sir John, including the application of hypo as a fixer, the cyanotype and other processes – even the very word photography itself. Preserving his family’s long reputation as astronomers, at the end of photography’s first year in the public eye, December 1839, he successfully made three negatives on glass to preserve the memory of his father’s famous forty-foot telescope. It was with this instrument that Frederick William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus, radically altering our concept of the solar system. These negatives are still in fine shape today, and in 1890, twenty-five prints were made from one of them and framed up in the rungs from Sir John’s twenty-foot telescope that he had used to such effect in Cape Town in the 1830s, just before photography became public. One hangs on the walls of Rock House.

guest post by Rose Teanby

In the summer of 1843, accompanied by Nicolaas Henneman, Henry Talbot took his cameras into France. There were two main motivations for this trip. He was already planning the illustrations for The Pencil of Nature and he had hopes of establishing the Calotype in Paris.

Ships in a harbour through a curtained window, Rouen (digitally enhanced)

Henry Talbot arrived in the medieval French city of Rouen in May 1843, breaking his journey from Calais to Paris.But as he signed the visitor’s book at the Hotel l’Angleterre overlooking the busy docks, it cannot have escaped his notice that Rouen presented two faces to the world. Rouen had become a city of two halves divided by the river Seine. Flamboyant gothic spires punctured the old city’s medieval skyline, like a needle through Rouenaisse fabric, and across the river at St. Sever a forest of chimneys and smoke would eventually dominate the Normandy landscape.

An 1844 edition of monthly arts journal The Artizan described Rouen as holding an unrivalled geographical position, sixty seven miles north west of Paris, forty four miles from the port of Havre, and connected to both by the “noble navigable” river Seine. The city led production of cotton goods, their checked cotton fabric now gaining the eponym “Rouenneries” and led to a necessary enlargement of Rouen’s capability as a port. But the older parts of the city were unsuited to new industrial methods of production. The city was not in a phase of transition, it was a city struggling to cope with two separate identities.

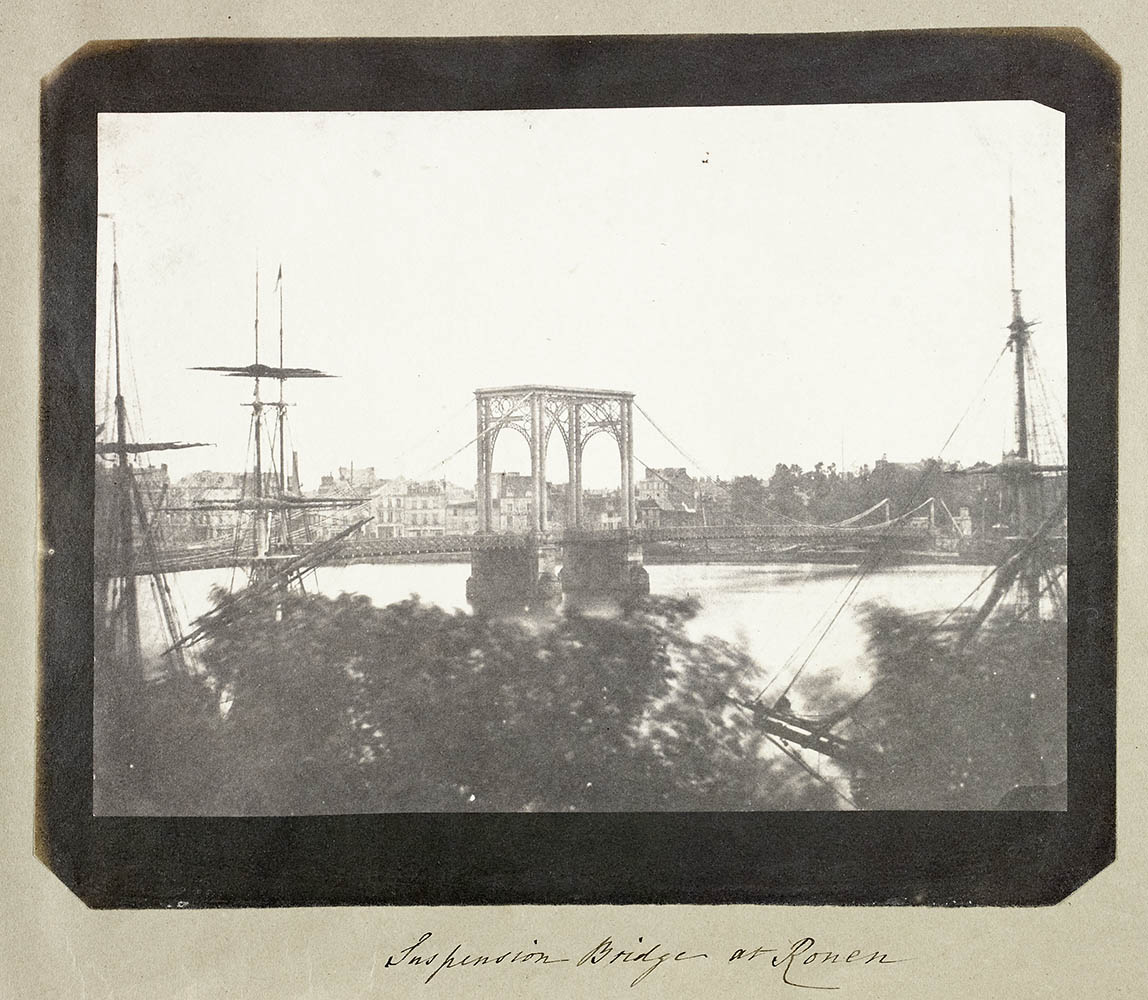

The English were already welcome visitors to Rouen. Eminent civil engineer Joseph Locke supervised construction of the Paris – Rouen railway which opened for passengers on 3 May 1843, two weeks prior to Henry’s arrival, interconnecting this key area of northern France. Rouen was now open for business with Paris by rail and river, with a new bridge presenting itself as a fitting subject for Talbot’s growing French portfolio. The influence of Janus spanned the river Seine in the form of a graceful iron suspension bridge linking the old city to a new French revolution, of manufacturing industry.

Le Pont Suspendu was designed by Marc Seguin and constructed by the Seguin Brothers, using wire cable suspension, opening for road and pedestrian traffic in September 1836. Seguin frères’ ornamental structure incorporated suggestions of the intricate iron tracery forming Rouen Cathedral’s new cast iron spire, with the logistical practicalities of transport management from one side of the river to the other. Water borne traffic, annually totalling in excess of 3000 vessels, could sail unhindered along the river Seine due to an innovative central arch fitted with a lifting apron. But the bridge roadway measured barely five metres wide along two ninety metre spans.

Its central position gave Talbot an unrivalled view from his elevated vantage point, focusing on the bridge itself rather than its usual depiction as a convenient conduit to the unmistakable landmarks of the old city. But the delicate balance of beauty and practicality came at a price.

The bridge became a victim of its own success, its delicate frame incapable of supporting the growing demands of the Rouenaisse, and was carefully demolished in 1884. Talbot’s photograph then joined Hungerford Bridge – ephemeral structures erased by urban development.

He reported back to Lady Elisabeth: “A new suspension bridge crosses the river before my windows. Great bustle and commercial activity manifest everywhere. From early dawn to dewy eve incessant rumbling of carts & wagons- Ships constantly loading, unloading, and moving away – at one moment the quai strewed with large barrels – an hour afterwards not one of them left.”

Talbot observed a similar scenario to his view of Westminster in 1841, the fluid artery of a major city, its bridges and riverbank activity and all its associated unceasing noise. But the dismal weather soon dampened his enthusiasm, choosing to photograph the window of his expensive hotel room, framing a distant view of the Seine’s river traffic. His letter continued “Weather grown extremely stormy and rainy – nothing to be done in Calotype until it clears up.”

The regions of France were encouraged to affirm their individual identity, particularly in the celebration of their unique historic monuments. Rouen was the capital of Normandy and claimed a status of historical importance coupled with unique examples of “flamboyant” gothic architecture. Artist Gustave Courbet described the quality of Gothic monuments and pleasing views “…Rouen is in this respect the richest town in France.”

In 1832 Joseph William Mallord Turner chose to depict Rouen in impressionist oils. Even Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre had chosen a view of the city of Rouen for the Diorama in 1826, painted by his creative partner Charles Marie Bouton.

Talbot may not have intended his brief diversion to Rouen to be as significant as it has become, but during those four days of miserable weather, the creative baton was handed from art to photography – from Turner to Talbot. During a brief “éclairci” from bad weather, Henry took his camera half a mile from the hotel and into another era of history. Le Palais de Justice was one of the secular buildings of medieval Rouen, completed in 1508, occupying three fifths of an acre in a three sided quadrangle. It was described as an elaborately florid style “sumptuous in its decorations both without and within; its triple canopy windows enriched with mullions and tracery.”

Talbot concentrated on the ornate detail of these windows, isolating the intricate elements sculpted by skilled stonemasons over three centuries earlier. Now housing the Rouen criminal courts, Le Palais de Justice represented Henry’s liberation from rain-soaked captivity. The image above stands in magnificent contrast to his study of the lace curtained view from within the Hotel l’Angleterre. This time he was outside looking in.

In anticipation of subsequent visits, Talbot advised his contemporaries “Rouen possesses many edifices of great architectural beauty, which lovers of Photography would love to delineate.” He was clearly correct. Between 1852 and 1864, vistas of Rouen were displayed on seventy one occasions in British exhibitions, all concentrating on architecture, Le Pont Suspendu conspicuously absent from display. The photographers following Talbot included Claude-Marie Ferrier, Philip Henry Delamotte, Charles Kinnear, Bisson frères, Stephen Thompson and Robert Howlett.

As 1858 advanced from summer to autumn, Howlett travelled to Rouen with the latest, cutting edge technology – a stereoscopic camera, new orthographic lens and collodion glass plates. Photographic technology had advanced at a rapid pace in the fifteen years since Henry’s calotype adventure, with the introduction and refinement of three dimensional imaging. Howlett “commenced work one fine morning in Rouen”, taking some of the final photographs of his short life, subsequently displayed posthumously in January 1859.

A Photographic Society Exhibition reviewer commented: “The architectural view was also one of the most beautiful things we had ever seen. It was a view of the “Palais de Justice, Rouen.”

Some of Talbot’s photographs mark a particular point in the evolution of a particular location, but Rouen remains defiantly resistant to change. Le Palais de Justice still stands majestically as it did for Henry, but now displaying the scars of WWII bombardment. The four bridges across the Seine became inevitable casualties of war, destroyed by conflict then rebuilt when peace prevailed.

Photographers still follow Talbot 175 years later, in pilgrimage to the city of magnificent gothic architecture, to capture the enduring resilient medieval beauty of Rouen, even in the rain.

Rose Teanby

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • The author wishes to thank David Greenfield for additional research regarding Le Pont Suspendu. • WHFT, Ships in the Rouen harbour, seen through a curtained window, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 16 May 1843, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2533/13; Schaaf 2726. The only known print of this, in one of Lady Elisabeth’s albums, is faded, perhaps from having suffered too much admiration. • The Artizan, no. 18, 29 June 1844, p.140. • “Opening of The Paris and Rouen Railway,” The Railway Times, 13 May 1843. • Theodore Licquet, Rouen, Its History, Monuments and Environs, 7th ed. (Rouen, 1869), p. 130. • WHFT, Suspension Bridge at Rouen salted paper print from a calotype negative, 15-18 May 1843, NSMeM, Bradford, 1937-2533/14; Schaaf 1899. • WHFT to Elisabeth Theresa Fielding, 15 May 1843, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 04824. • WHFT, The Seine at Rouen, salted paper print from a calotype negative, 15-18 May 1843, NSMeM, Bradford, 1937-2533/15; Schaaf 1927. • Stephen Bann, Distinguished Images (Yale University Press, 2013), p. 48. • The Monthly Magazine, v. 1 , January-June 1826, p. 305. • The Stereoscopic Magazine, no 23, May 1860, p. 73. • WHFT, Palais de Justice, Rouen salted paper print from a calotype negative, 15-18 May 1843, NSMeM, Bradford, 1937-2535/1; Schaaf 1445. • Larry J Schaaf, The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton University Press, 2000), p. 158. • Letter dated 5 November 1858 from Robert Howlett to Photographic Society Journal, 22 November 1858, p. 74. • “Photographic Society Ordinary General Meeting” (7 December 1858), The Photographic News, 10 December 1858, p.165. • Robert Howlett, Palais de Justice, Rouen, stereo photograph, 1858, courtesy of a Private Collection.