Given Henry’s early and intense interest in mathematics, we must not forget that Wednesday this week was National Pi Day (3.14) and renew our pondering of just what Talbot might have thought of digital photography.

Like many, I was devastated when Monday morning brought the terrible news that Pete James had passed away the previous evening. Born in 1958, professionally Pete was Head of Photography at the Library of Birmingham for more than 25 years until his job was criminally swept away in 2015. His interest in the history of photography was triggered in the late 1970s: “I was working at the Kodak plant in Harrow … used to visit the Kodak Museum a lot during breaks.” Had the gods been kind, I should have met Pete then during one of my visits. The late Brian Coe was a jovial host at the Museum, a small facility housed within one of the factory buildings at Harrow (not far from where Nicolaas Henneman had established his Kensal Green printing works in 1851). Pete was an FRPS, at various times he was the Chairman of the Committee of National Photography Collections and a founding member of the Photographic Collections Network. He had bravely battled a variety of debilitating health problems for some years. Although these frequently sapped his energy, they never triumphed over his spirit. Pete brought back memories of the late Arthur Gill. Arthur and I used to traipse around London and elsewhere, visiting the scenes of photographic studios long gone, picking up the vibes if you will of neighborhoods and physical relationships between historically significant plates. Not so long ago, Pete took me on a magical mystery tour of his native Birmingham, freely sharing his encyclopedic knowledge and particularly his unflagging enthusiasm. I was able to assist him a little bit on his research for re-creating Talbot’s 1839 exhibition in Birmingham, an extraordinary event brought back to life by Mat Collishaw’s Thresholds. The richness of this experience was down to Pete’s meticulous research. He did one blog for us – others were planned – and right up until his last days was still continuing his research and ambitiously planning future events. One obituary is in the online British Journal of Photography and a fuller one is coming on the British Photographic History website. Through my moist eyes and memory-stoked smiles, I have asked a few mutual friends to share their reactions.

Pam Roberts, former Curator of The Royal Photographic Society: I first met Pete nearly three decades ago when he visited the RPS in Bath. Our mutual friend, John Taylor, assured me that Pete was the greatest guy ever and that we would hit it off and absolutely love each other. We did not. Pete, morose, grumpy, newly abstaining from alcohol, also had terrible flu. Amazingly, our second meeting went swimmingly, as did all of them since. I watched Pete grow from an under-confident researcher and uncertain writer into the terrific curator, researcher, author, educator, lecturer and mentor that he became. All this despite his increasing degree of debilitating illnesses over the years. We spoke on the phone for hours, exchanged long faxes, then even longer emails. Boy, did we have great emails over the years!! Most of which I still have, still read, still make me laugh. Now, as I look back on them, they make me cry. In the late 1990s, when the RPS Executive decided that the RPS Collection must be relocated to another institution, Pete and I put up a good fight for his home institution, the Birmingham Public Library, a battle we lost. To know Pete was to love him and it was always a joy to see him, enjoy his eternal optimism and laconic wit, his sardonic humour, and listen to his very lovely mellifluous voice. He is a huge loss as a bastion of British photography. Pete’s mother still lives in Romsey, our country village, so over the years Martin and I enjoyed frequent visits by Pete and his family. Soon those emails will make me laugh once again.

Rose Teanby, photohistorian: It was over a pot of tea just five weeks ago that I met Pete in person for the first time. We had been corresponding for a while and in that now-short time I gained so much. Pete was so generous with both with his vast knowledge and with his personal time, willing to share whatever would help progress my research. He emailed from his hospital bed, hopeful of a return to health, all the time supporting my work while planning his next piece of research. People like Pete don’t come along very often. His enthusiasm for photographic history and willingness to help others cannot be replaced. What I will treasure most is the sincere kindness he always showed, especially whilst discussing our respective bright plans for the future.

Lindsey S Stewart, Bernard Quaritch Ltd.: Pete and I correspond long before we first met in person maybe 20 years ago. I was at Christie’s and he was already building the outstanding collections at the Birmingham Library. I was immediately struck by what a kind, funny and patient individual he was in a world even then too full of busy-ness and bluster. We worked together on projects spanning everything from the earliest photographs to the archives of living photographers. Pete cared passionately about everything and always made things a pleasure. He was one of the most creative thinkers, most hard-working, most effective and yet most modest people I’ve come across. He kept his wicked sense of humour throughout his health ordeals. What a loss to our small field. Pete will be greatly missed.

Michael Pritchard, Chief Executive, The Royal Photographic Society: I don’t remember when I first met Pete but it must have been soon after he joined the Library of Birmingham, brought together through a shared fascination with photographic history. Over the years we kept in contact responding to each other’s questions and meeting up at conferences and meetings. In January Pete was excited to share his plans for his work on George Shaw. Pete was more than just an excellent historian, he had a broader interest in photography and he was also a pretty good photographer himself, as anyone who followed his social media posts will know. In a field that is relatively small we’ve lost a giant amongst us, and many, many, of us will have lost a personal friend. He’s irreplaceable but there’s a great legacy through his publications and writings.

Mat Collishaw, artist: Pete was a sly old fox, a sensitive and gentle man with a steely will and a reservoir of knowledge. The first time we met we spent a thoroughly enjoyable couple of hours trawling through old police crime scene photographs, mainly of public toilets in the West Midlands area. He was able to give these unsavoury images a similar gravitas as to all material that came under his detectives eye. Every picture held a potential clue and for every clue he had a possible lead, always searching for connections. He was the internet before the internet, an invisible network of obscure information.

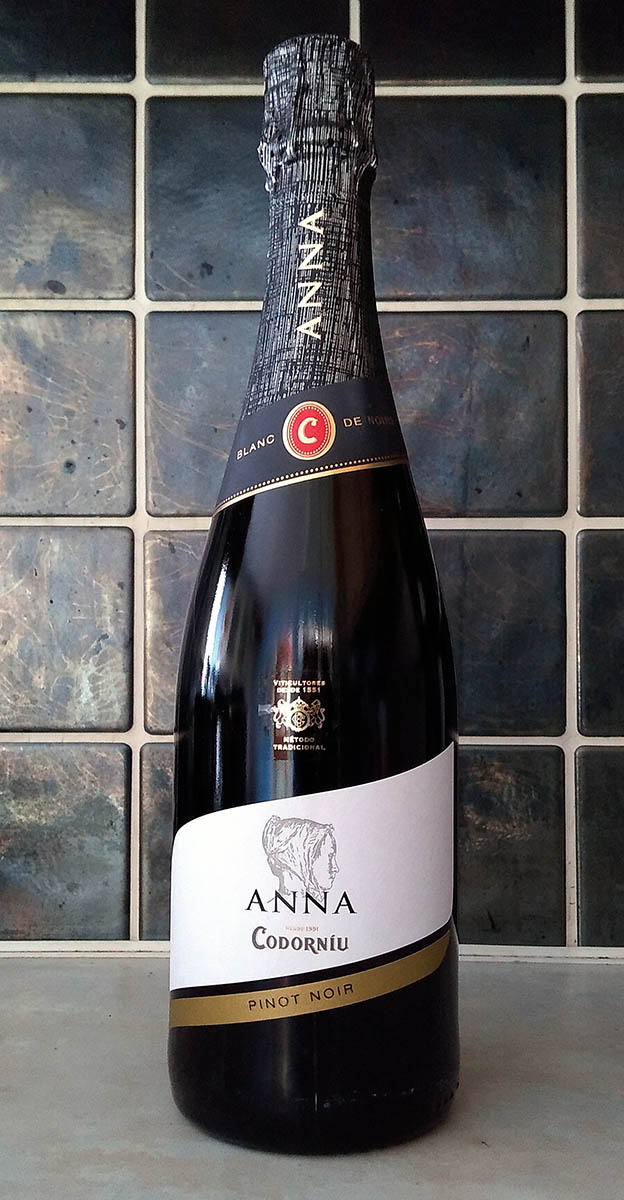

Today is Anna Atkins’s 209th birthday and I trust you will be opening an appropriate bottle to celebrate it. Atkins (16 March 1799 – 9 June 1871) was one of foremost of those imaginative and fearless souls who took on the young art of photography and shaped it to society’s needs. Her Photographs of British Algæ: Cyanotype Impressions was a bold decade-long foray in creating and publishing the first book illustrated with photographs, pre-dating even Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature. Atkins gave one of the first copies of her book to Talbot, for he had taken the time out to personally demonstrate photography to Anna and her father John George Children.

Since International Women’s Day was last week, this is a good time to point to a new blog, one crafted by non other than our periodic blog contributor Rose Teanby. Titled Early Woman Photographers, its thoroughness and refreshingly jargon-free wording upcycles Rose’s legal background to a fine use. Rose has been working closely with Graham Harrison, whose Photo Histories should already be on your e-reading list.

I have never seen one of Henry Talbot’s 1839 Io-types and don’t know of any 19th c. reports on them. Thus, it came as quite a shock when my old friend Grant Romer, phrenologist, conservator, raconteur (and believe me, a performer that you do not want to follow in a conference) presented me with a reincarnation. Studying Talbot’s notebooks P & Q with a trained eye, practised hands, and an active imagination, Grant decided to try to bring this process to life. Perhaps not surprisingly, he succeeded. I was tipped off by our mutual madcap friend, Carlos Gabriel Vertanessian, who slipped me some snapshots that made me feel that I was seeing a ghost.

Last autumn, at a conference at the National Library in Argentina, Grant first publicly revealed his work. He is back in Argentina this week and did not have time to write this section of the blog himself (the route that I would have preferred). But I have pilfered his words from private communications in order to bring his exciting project to wider attention.

In starting down his path of re-creating Talbot’s lost experiments, Grant observed that “prior to 1839, Talbot began a number of experiments exploring methods of coloring the surface of metals. He became intrigued by the effects of iodine on sheets of copper and silver-leaf on glass and coined the term ‘Io-type’ for one of these processes. That term is used here broadly to describe an imaging system based on one of these early experiments. Very long exposure of an iodized silver surface forms a positive image by the action of light alone – no developing is required.”

What is amazing is that, in Grant’s words, “the resulting photographs are highly colored. The interference colors are due to the thin Iodine layer. On exposure to light, silver crystals are formed in that thin layer – depending on their size and shape, different colors result due to reflection of light off of the silver surface back through the Iodine layer. There are many things going on at different stages of light exposure. It bent the brains of many and remains largely un-investigated scientifically. I do not trust my own explanation and understanding. It is Physics. The positive image is formed of silver … the colors produced by interference. I prefer to explain the process no further than that.”

The colours are ‘false’ ones, not corresponding to those in nature, but the range of effects that Grant has managed to produce so far is outstanding. He has echoed Talbot’s early work with photograms of plants. Don’t miss the extraordinary three-dimensionality of this example.

the top quarter is after five hours exposure to daylight – the bottom part was covered

These Io-types can be fixed, but while making them more permanent it sadly eliminates the colours, making the image resemble a mercury-developed Daguerreotype. Some of them have already been destroyed by light. Grant believes that “the exposure to light was sufficient to cause the silver to darken,” speculating that “a longer exposure, ten hours or more, might result in a reversal of tone, a whitish development instead of the darker brown. In essence, the reflective mirror surface of the ‘white’ silver plate has become a non-reflective brown surface.” While these fascinating colours are ultimately fugitive (at least at this stage), Grant gamely says that “they were made in play and can perish in play – tell me what you discover and I will be very pleased.”

And if you can make it to London in May, you will have the fantastic and unique opportunity to see some of Grant’s original Io-types on display, probably mutating through the five days that they will be up.

And if you can make it to London in May, you will have the fantastic and unique opportunity to see some of Grant’s original Io-types on display, probably mutating through the five days that they will be up.

The neoclassical Somerset House on the Strand in London was the home of The Royal Society when Henry Talbot presented his first paper on photography on 31 January 1839. This year, for the short period of Thursday 17 May through Sunday 20 May, Talbot’s original photographs will be returning to this historic site. Last year, Photo London’s international fair hosted the premier opening of Mat Collishaw’s augmented virtual reality show, Thresholds. This year, Grant Romer’s Io-types will be shown in Sun Pictures Then and Now: Talbot and His Legacy Today, curated by Hans P. Kraus, Jnr. There will be an interesting duality to this exhibition, for it will feature works not only by Grant but also Adam Fuss, Vera Lutter, Abelardo Morrell, Cornelia Parker, Mike Robinson, and Hiroshi Sugimoto. Everything these contemporary artists will be displaying was directly inspired by the works of Henry Talbot and, from what I have seen so far, it will be a diverse and stimulating show. Equally importantly, there will be a very substantial exhibition of original negatives and prints by Talbot himself, bolstered by photographs from some of his colleagues and also manuscript and rare printed material. Although frustratingly short in its run, it promises to be one of the most significant Talbot exhibitions of recent times.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • I think that Pete would have appreciated this composite portrait – made with apologies to Silverbox Studio in Lisbon for the aluminotype and to the caricature of one of Pete’s heros, Sir Benjamin Stone, a lithograph from Vanity Fair, February 1902. This week I have changed my mug shot to the tintype/aluminotype taken in October 2016 at the same session as Pete’s portrait. We were both speaking at the Stereo and Immersive Media conference, brilliantly arranged by Victor Flores. • There are many other Talbot experiments waiting for someone to follow Grant Romer’s inspiration and try to bring them back to life. Above is P107, the entry from 13 September 1839, drawn from my Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). • WHFT’s “Remarks on M. Daguerre’s Photogenic Process” are recorded in the BAAS Report for 1839, Transactions of the Sections, pp. 3-5. An unofficial but somewhat more lively discussion about them is in The Athenæum, no. 618, 31 August 1839, pp. 643-644. • On a related note, it may be of interest to read Talbot’s letter of 21 December 1842: “On the coloured Rings produced by Iodine on Silver, with Remarks on the History of Photography,” Philosophical Magazine, 3rd series, no. 143, February 1843, p. 97.