Last week, our Research Affiliate Édouard de Saint-Ours contributed some of the fascinating results of his close study of Talbot’s 1843 photographs of his home town, Paris. There was so much new insight that I couldn’t bear to cut much and he set the record for the longest blog that we have ever published. I believe that he has broken that record once again.

Part of the problem in examining Talbot’s Parisian photographs is that the 1860s were in some ways similar to the 1960s. In the 1960s, a combination of riots, and much more damagingly, urban planners, ripped up the histoirc fabric of many of our cities in order to modernise them. The crumbling results are something that we still have to live with. Just fifteen years after Talbot’s photography, Baron Haussmann had this entire area demolished to make way for his vision of Paris – at least a jolly nice opera house resulted from it.

Several readers, including Geoff Batchen and Serge Plantureux, weighed in the idea of Talbot’s being the first panoramas, and indeed they were not. My personal favorite was Antoine Claudet’s 1842 Daguerreotype panorama of London, taken on a series of plates and reproduced grandly through wood engravings in the Illustrated London News. This is just the north half!

Finally, Hans P Kraus, Jr, shared a couple of interesting negatives from his enormous collection. Édouard was immediately able to put them into context and they are shown below. These negatives have always raised some questions. We know that Talbot was photographing in this part of Paris. We know that Henneman at least assisted him with some and may well have taken some of the negatives. And to my eye, Mr Kraus’s negative evoke the distinctive photographic style of the Rev Calvert R Jones, who also was in Paris and of course shared the same basic photographic materials supplied by Henneman. We can be pretty confident that the larger negatives dated in Talbot’s hand were by him. I suspect that some of the smaller negatives were by Henneman working beside him. And I continue to wonder if Rev Jones either suggested or used the same hotel windows for some of his Parisian images. Opinions welcome.

Guest Post by Édouard de Saint-Ours

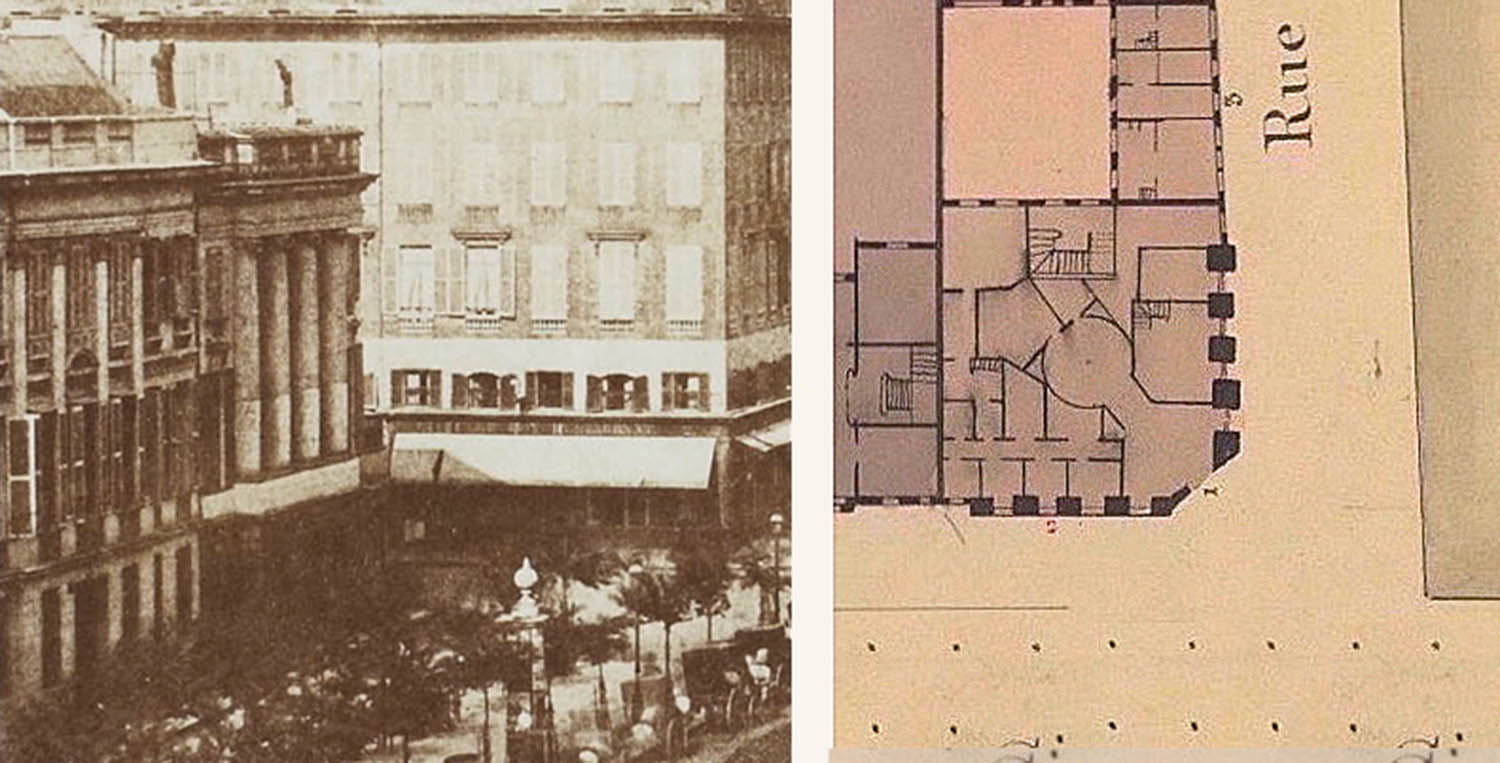

From 19 May to 13 June 1843, Henry Talbot was in Paris with his assistant and former servant Nicolaas Henneman. They had come to instruct French aspiring calotypists as part of a commercial arrangement between Talbot and Hugues Antoine Joseph Eugène Maret, marquis de Bassano. While in the French capital, Talbot stayed at the Hôtel de Douvres, at the corner of boulevard des Capucines and rue de la Paix. As he remarked in a letter to his mother , Lady Elisabeth Feilding, dated 22 May, the apartment he rented on an upper floor had a circular sitting room overlooking the boulevard. This urban observatory enabled Talbot to photograph it under all angles and at different times of the day. It also allowed him to experiment with panoramic photography, as I have discussed in last week’s blog post .

Although Talbot’s photographs barely hint at human presence on the street, boulevard des Capucines was in fact the very heart of Parisian activity in the 1840s. Until the end of Louis-Philippe’s reign in 1848, the boulevard attracted sociable and wealthy young men, who spent a good part of their idle days at the Café de Paris, the Maison Dorée or the Jockey Club. It was also animated throughout the day by street musicians and buskers.

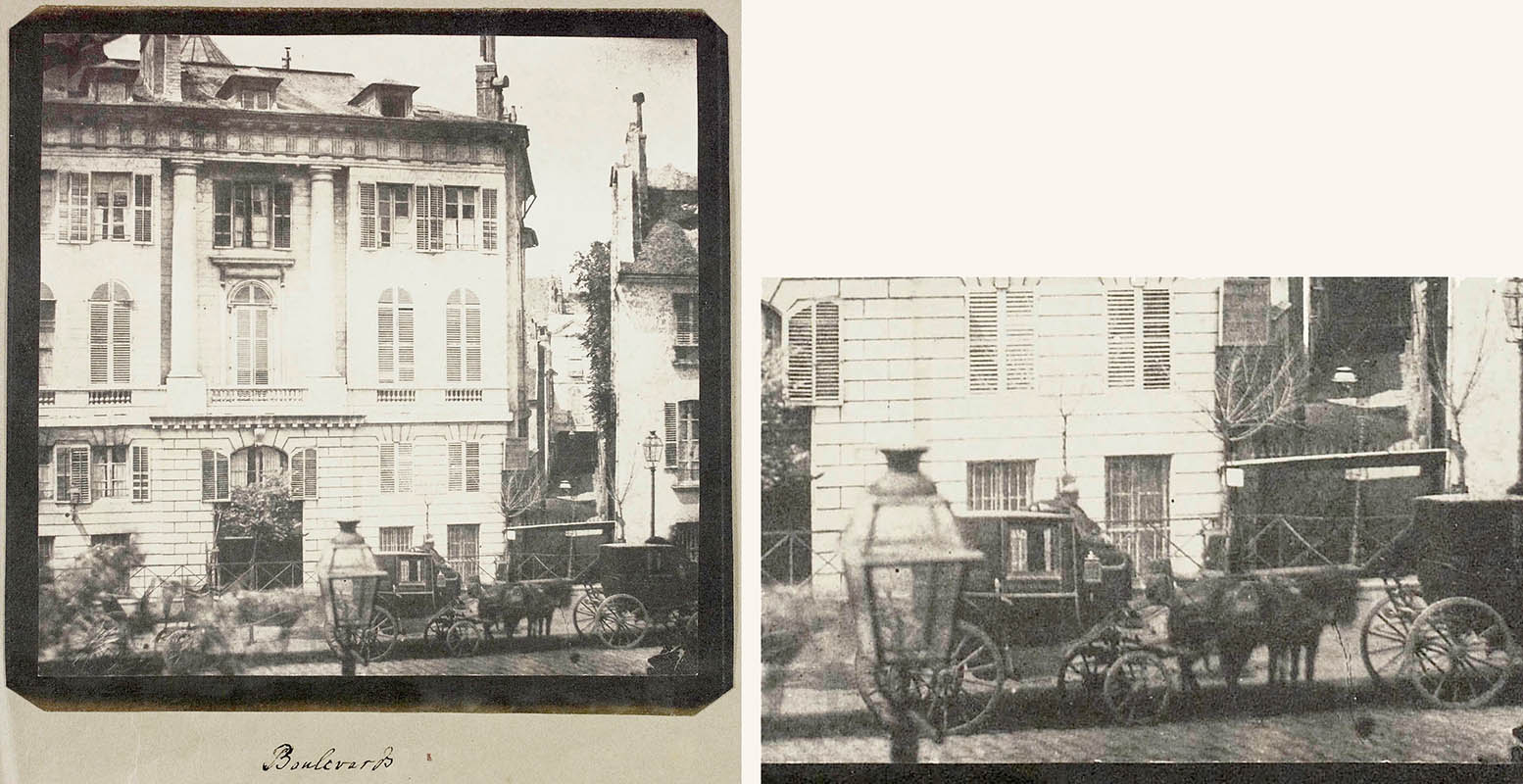

The majority of the photographs taken from the Hôtel de Douvres depict the north side of boulevard des Capucines and the buildings on rue Basse-du-Rempart, from n° 24 to n° 2 (from west to east). In these images, the ground floor of the apartment blocks and townhouses across the street is often obscured because rue Basse-du-Rempart was at a lower level than the boulevard itself. The two streets were separated by a railing and connected by stairs that can be seen in the pictures.

All boulevards in Paris replaced former defensive walls. The French word ‘boulevard’ originally meant ‘rampart’ and shares its German etymological root with the English word ‘bulwark’. Boulevard des Capucines was built on the wall of Louis XIII, lowered for this purpose at the end of the seventeenth century. Rue Basse-du-Rempart (meaning Low Rampart Street) thus ran along the north side of this former wall, where the ditch used to be.

Historical Buildings

Today, Talbot’s photographs are a valuable source of information about an area that was torn down in 1858 to make way for the new opera house and its square under Georges Eugène Haussmann’s transformation of Paris. Most of the buildings shown in the pictures were destroyed, including the Hôtel de Douvres in the late 1860s. Some of them had particular historical importance and it is a pity they can no longer be seen.

For example, at n° 8 rue Basse-du-Rempart used to stand the Hôtel Radix de Sainte-Foix, a luxurious palace built in 1775 from a design by Antoine-François Brongniart for the then-Treasurer of the French Navy, Bouret de Vézelay. It was sold in 1779 to Maximilien Radix de Sainte-Foix, whose name is now attached to the building. It changed hands several times before being inhabited by the marquise d’Osmond, who held a renowned salon there in the 1840s. The building can be seen in several photographs taken from the Hôtel de Douvres (Schaaf nos. 115, 116, 118, 119, 121, 122, 5546, 5547).

Some of these pictures also show the Hôtel de Montmorency, designed by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and built in 1775 at the north-west corner of boulevard des Capucines and rue de la Chaussée d’Antin (Schaaf nos. 115, 120, 122, 123, 128). In the early nineteenth century, it belonged to Gian Battista Sommariva and hosted his formidable art collection, which became accessible to the public after his death in 1826. It was replaced in 1866-68 by the Théâtre du Vaudeville. And in 1927, it became a cinema theatre, which it still is today.

Features of Parisian street life

Although the crowd that thronged the boulevard could not be fixed on the calotype negative, most photographs taken from the Hôtel de Douvres retain the image of the many horse carriages that lined the pavement, waiting to be hired.

A coachman kept still long enough upon his seat to be represented in a picture taken from Talbot’s hotel. Carriages seem to have been a particular focus of interest for him, being the only element of street life that could remain motionless long enough to be secured on the calotype negative.

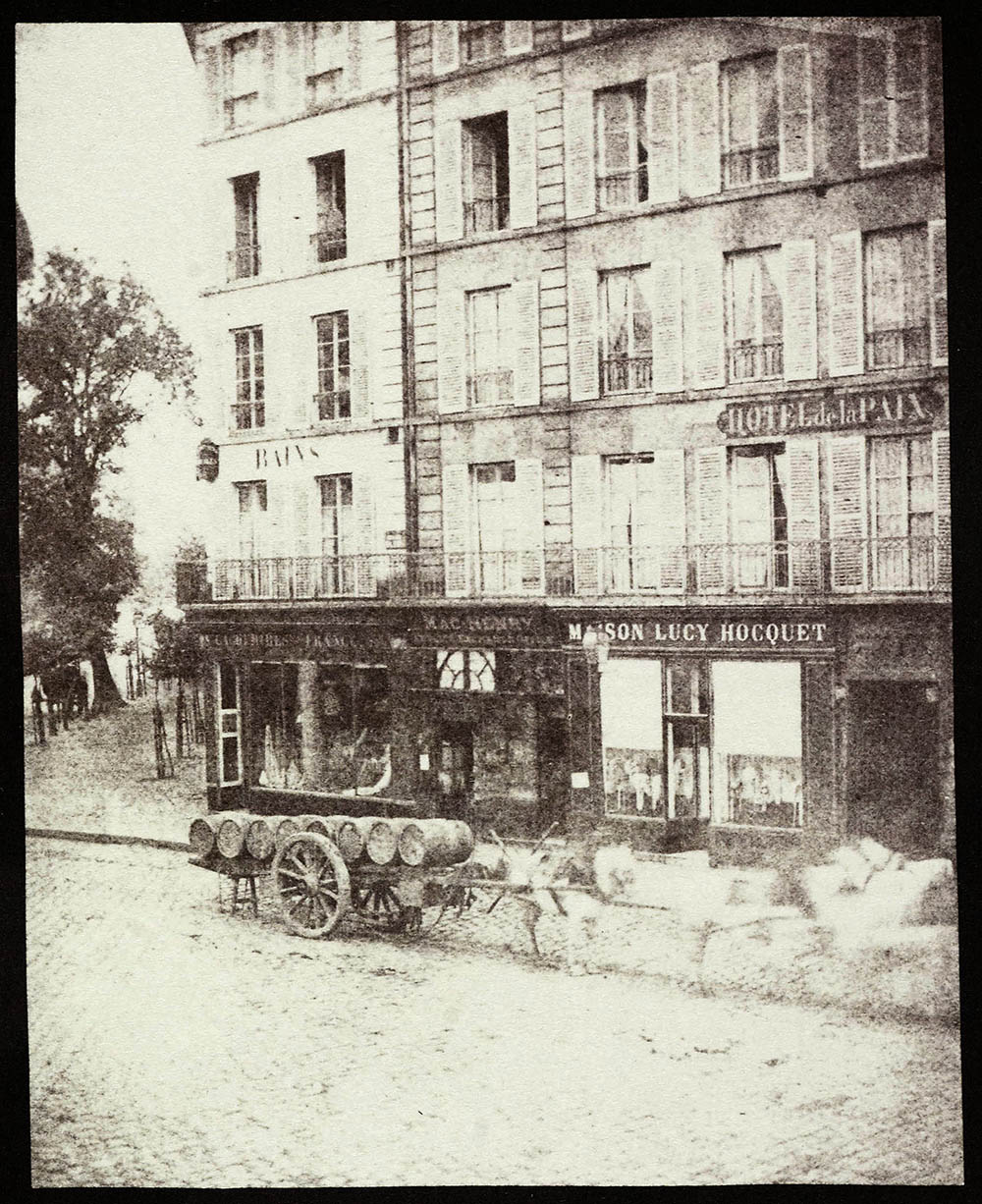

Another photograph depicting the north end of rue de la Paix, shows a horse cart parked across the street, resting on holds, and loaded with eight barrels. The horses, having moved during the exposure, are reduced to a foggy presence, but the cart itself remained still enough for it to be sharply represented in the negative. Although devoid of human presence, this is probably one of the only unstaged genre scenes photographed by Talbot.

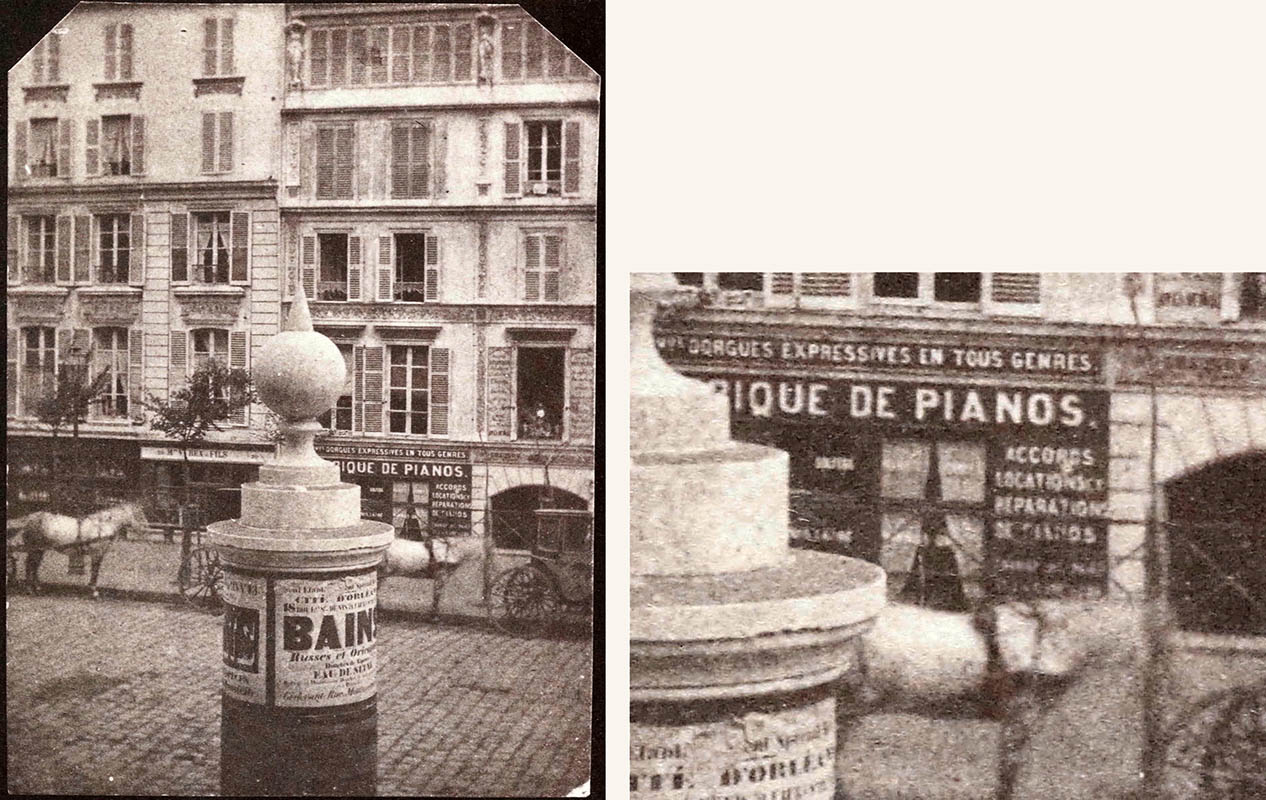

Another feature of Parisian street life is often represented in these views: the newly installed vespasiennes, also called colonnes Rambuteau, serving both as urinals and advertising medium. Topped by a pointed sphere, they were installed by Claude-Philibert de Rambuteau, préfet de la Seine between 1833 and 1848, who also generalised the use of gaslight in Paris. The boulevard was equipped with gas lamps in 1837. Easily spotted in the photographs taken from the Hôtel de Douvres, they were described by Talbot as producing a ‘splendid effect’ at night on place de la Concorde.

Paving the boulevard

In Talbot’s most famous photograph of boulevard des Capucines, published in 1844 as plate II of The Pencil of Nature , the roadway is obviously being repaved, while other pictures show a smooth cobbled surface (Schaaf nos. 115, 120, 123-127, 129, 132, 133, 1637, 1914, 2747).

Although fully paved since the end of the 18th century, the boulevard remained uneven. The city’s authorities endeavoured to level its course with the lower streets, and regularly tried out new paving solutions. In 1837, asphalt replaced cobblestones. The boulevard was lowered in 1839, and in 1841 or 1842, wooden blocks were tested without success.

The photographs taken by Talbot indicate that new paving work was undertaken on this section of the boulevard in May and June 1843. It is difficult to make sense of these images chronologically. However, judging from the date written in Talbot’s hand at the back of two calotype negatives from the collection of the Musée des arts et métiers, in Paris, boulevard des Capucines was fully paved on 1 June 1843.

Plate II of The Pencil bears witness to the work being undertaken there on a ‘hot and dusty’ afternoon. In the text accompanying the print, Talbot described the scene: “they have just been watering the road, which has produced two broad bands of shade upon it, which unite in the foreground, because, the road being partially under repair (as is seen from the two wheel-barrows, &c., &c.), the watering machines have been compelled to cross to the other side.”

As has been pointed out before by several scholars, Talbot’s choice for plate II of The Pencil indicates his intention to rival one of Daguerre’s most famous daguerreotypes. Depicting boulevard du Temple in Paris, it was taken from the inventor’s window on a similar day five years earlier. This analogy is confirmed by Talbot’s text for The Pencil, in which he makes an implicit reference to the many descriptions of Daguerre’s plate published in the press and that emphasised its dazzling precision. Photographs still had to be copied by an engraver to be reproduced in print, and daguerreotypes only existed as unique objects. Therefore, most people only knew about Daguerre’s plates through written descriptions. In The Pencil, Talbot insists on the precision of his own (reproducible) process, overtly rivalling the daguerreotype’s main advantage: “A whole forest of chimneys borders the horizon: for, the instrument chronicles whatever it sees, and certainly would delineate a chimney-pot or a chimney-sweeper with the same impartiality as it would the Apollo of Belvedere.”

According to Talbot , the weather in France was cloudy and wet, except on his first day in Paris, 20 May. The photograph reproduced in The Pencil may have been taken at that time, as suggests his remark that it was a ‘hot and dusty day’. In that case, the negatives showing a fully paved boulevard des Capucines would have been taken after paving was completed some days later.

Commercial activity on the boulevard

Talbot’s pictures document one of the only subsisting sections of rue Basse-du-Rempart at that time. Most of it had already been absorbed by the boulevard in the mid-1830s, and it ran from today’s n° 24 boulevard des Capucines to rue de la Chaussée d’Antin. Rue Basse-du-Rempart was then lined with modest businesses.

Talbot’s photographs show that there used to be a piano maker at n° 18 and two most eclectic shops at n° 10, respectively advertising the sale of ‘English cement, stucco, paving, works of art’ and of ‘leather, cardboard [?]’.

Talbot wrote to his mother that he had explicitly chosen the Hôtel de Douvres ‘on account of the view’. However, he may also have been encouraged by the fact that the hotel was situated in one of the hearts of British culture in Paris, as suggest the names of several hotels on rue de la Paix during the July Monarchy: not only the Hôtel de Douvres (n° 21), but also the Hôtel des Iles Britanniques (n° 5) and the Hôtel Canterbury (n° 24).

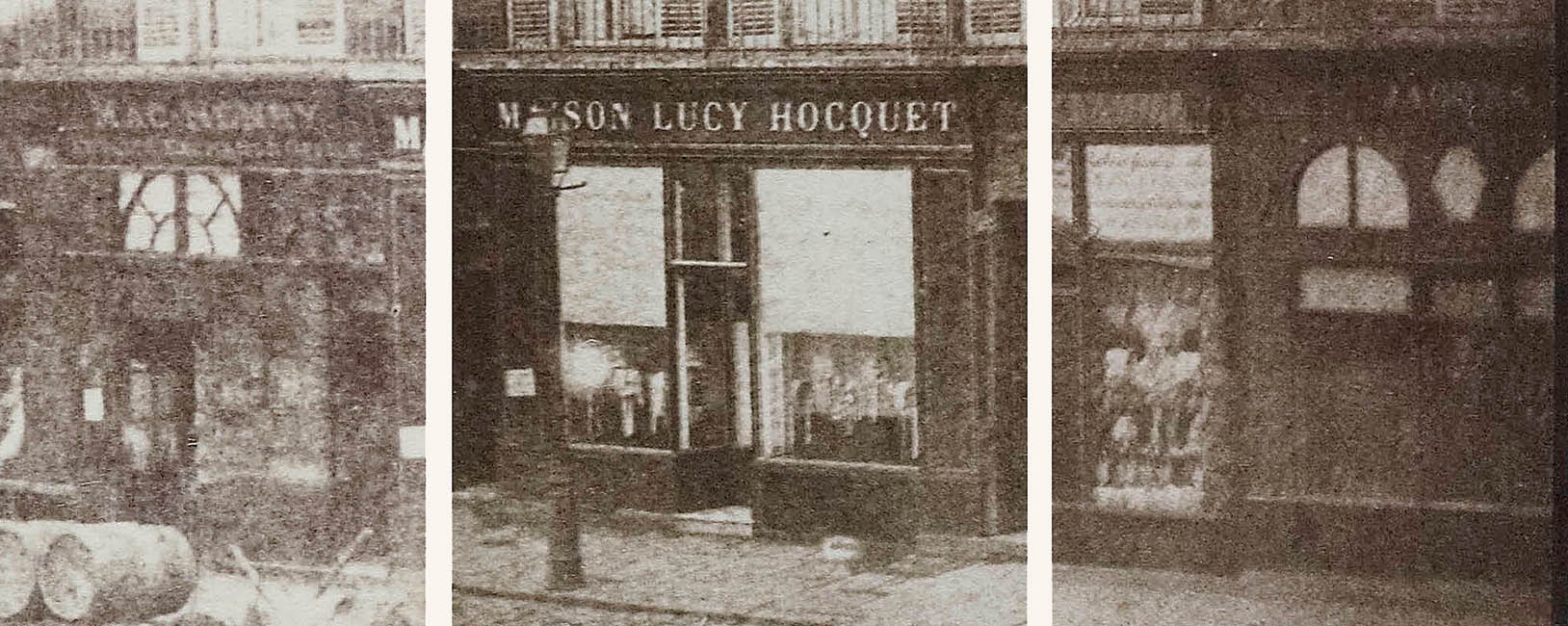

Favoured by foreign visitors to the French capital, these comfortable hotels had encouraged the establishment of British businesses in the neighbourhood. English shoemakers could then be found at n° 28 rue de la Paix. Just across from Talbot’s hotel, their shop signs can be read in two of his photographs: Mac Henry and Jacobs.

On that same street, during the July Monarchy, one could also find an English pharmacy, Budgett and Cooper; an English dentist attached to the British embassy, Mortimer (n° 11); and an Anglo-American bookstore, the Librairie française et étrangère (n° 11). In 1843, n° 28 rue de la Paix was also home to a renowned fashion designer, Lucy Hocquet, whose shop can be seen between Mac Henry and Jacobs. In 1845, Galignani’s New Paris Guide informed tourists that Lucy Hocquet was “Celebrated for her Head-dresses for Evening Parties, Balls and Court Receptions.”This specialisation in millinery is confirmed by the bonnets displayed in her window.

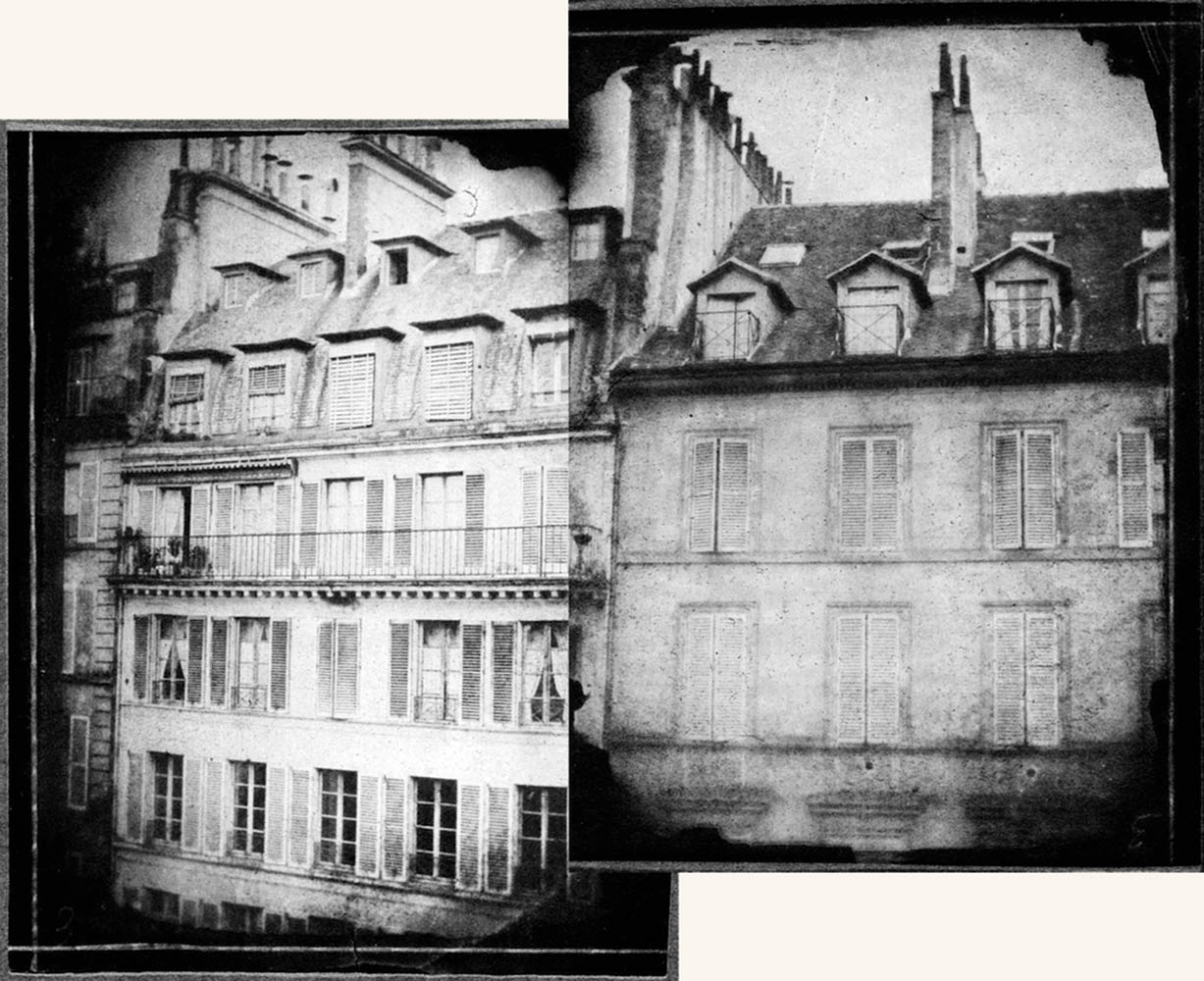

Talbot also photographed the upper floors of the buildings that hosted these businesses. At first, it seemed difficult to identify the location of the apartment blocks seen in four particular negatives. But it appeared that two of them matched quite well and could have been part of a panoramic experiment (Schaaf 1024 & 1028), as other sets of negatives taken by Talbot from his Parisian hotel .

At first there was no way to ascertain that these had been taken from the Hôtel de Douvres, although it seemed highly probable. So I looked for other photographs showing this section of rue de la Paix and found an albumen print by Louis-Émile Durandelle taken from the opera’s rooftop in 1868 , while the area was being destroyed to make way for the avenue de l’Opéra.

The two buildings from our negatives are clearly seen at the centre of the composition. All details match: the roofs, the number of windows, the balconies, the position of chimney tops, etc. Taking a closer look at the one on the right, you will see that its façade corresponds to Talbot’s photograph of the Hôtel Canterbury, at n° 24 rue de la Paix. Therefore, there is no doubt that our four negatives were taken from the Hôtel de Douvres and depict n° 24 and 26 rue de la Paix.

The photographs taken in Paris by Talbot from his hotel’s windows in May and June 1843 are very valuable to the historian of photography. They bear witness to his experiments with a process that he was trying to promote in France. But they are also of great interest for the history of Paris, because they illustrate an under-documented stage in the city’s urban development, as well as giving a rare glimpse into the boulevard’s commercial activity in the 1840s.

Édouard de Saint-Ours

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Édouard de Saint-Ours has kindly made available his background notes for his blogs as a downloadable pdf. • Wood engravings based on Antoine Claudet’s daguereotypes, London in 1842, Taken from the Summit of the Duke of York’s Column (north view), Illustrated London News, 30 July 1842, courtesy of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. • The standard reference on Talbot’s business relations with Bassano is Nancy Keeler’s ‘Inventors and Entrepreneurs,’ History of Photography, v. 26, no. 1, Spring 2002, pp. 26-33. • Most of the information regarding boulevard des Capucines, rue Basse-du-Rempart and rue de la Paix during the July Monarchy was found in Jacques Boulenger’s Le Boulevard: Sous Louis-Philippe (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1933), pp. 1-67; and in the entry for ‘CAPUCINES, boulevard des’ in Jacques Hillairet (ed.), Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris, Vol 1 (Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 2nd edition, 1964), pp. 264-66. • WHFT, Boulevards of Paris, salted paper print, 1843, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2533/11; Schaaf 116. • This detail shows the junction point of a composite image I made and used for a previous blog post . WHFT, Boulevards of Paris, salted paper print, 1843, National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2533/11; Schaaf 116. • WHFT, View of the Boulevards at Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-1292/1; Schaaf 128. • Detail from WHFT, View of the Boulevards at Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2535/05; Schaaf 128. • Both details from the parcel map are from the same sheet in the Atlas Vasserot (1810-1836): 3e quartier, Place Vendôme, îlot n° 15; Archives nationales, F/31/74/35. • WHFT, Boulevards of Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2533/07; Schaaf 129. • WHFT, Hotel de la Paix and Maison Lucy Hocquet, Rue de la Paix, Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2391/1; Schaaf 133. • WHFT, View of the Boulevards at Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2535/05; Schaaf 128. • About leveling and paving works undertaken on the boulevard in the nineteenth century, see Bernard Landau, Claire Monod and Evelyne Lohr (eds.), Les grands boulevards: Un parcours d’innovation et de modernité (Paris: Action artistique de la Ville de Paris, 2000), pp. 47, 49 ; Boulenger, op. cit., p. 12 ; Félix Lazare and Louis Lazare, Dictionnaire administratif et historique des rues de Paris et de ses monuments (Paris: Félix Lazare, 1844), p. 102. • A discussion about the analogies between Talbot’s and Daguerre’s depictions of boulevards can be found in Timm Starl’s ‘Prospect and View: On Daguerre’s and Talbot’s “Boulevards of Paris”,’ Camera Austria, no. 24, 1987, pp. 81-86. • WHFT, Boulevards of Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2387/3; Schaaf 126. • Detail from WHFT, Boulevards of Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2533/11; Schaaf 116. • WHFT, Hotel Canterbury, Rue de la Paix, Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2533/06; Schaaf 1637. • WHFT, Hotel de la Paix and Maison Lucy Hocquet, Rue de la Paix, Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2389; Schaaf 132. • Detail from WHFT, Hotel de la Paix and Maison Lucy Hocquet, Rue de la Paix, Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2391/1; Schaaf 133. • Details from WHFT, Hotel de la Paix and Maison Lucy Hocquet, Rue de la Paix, Paris, salted paper print, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-2389; Schaaf 132. • Galignani’s New Paris Guide (Paris: A. and W. Galignani and Co., 1845), p. 503. • WHFT, Rue de la Paix, Paris, calotype negative, 1843, NSMeM, 1937-4000; Schaaf 1024. • WHFT, Rue de la Paix, Paris, calotype negative, 1843, National Science And Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2396; Schaaf 1028. • WHFT, View from a window, rue de la Paix, Paris, calotype negative, 1843, courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr, New York; Schaaf 2703. • WHFT, Rue de la Paix, Paris, calotype negative, 1843, courtesy of Hans P. Kraus, Jr., Inc, New York; Schaaf 2702. • Digital positives derived from negatives Schaaf 1028 and Schaaf 1024. • Louis-Émile Durandelle, Place de l’Opéra, albumen print, 1868, Bibliothèque de l’École national des Beaux-Arts, Paris.