I’ve shamelessly appropriated today’s title from Robert Dodsley (1703-1764), a poet, author and publisher. He knew of what he wrote, for Dodsley had served as a footman in London before trading in his livery for the pen. In earlier times, the footman’s primary responsibility was to trot alongside the master’s or mistress’s carriage, ensuring that there were no threatening pits in the road or low-hanging branches along the path. As runners, they had to be physically fit, preferably with long legs, but just as importantly, as highly visible representatives of the aristocracy smart looks were prized. Their splendid livery was a part of this image.

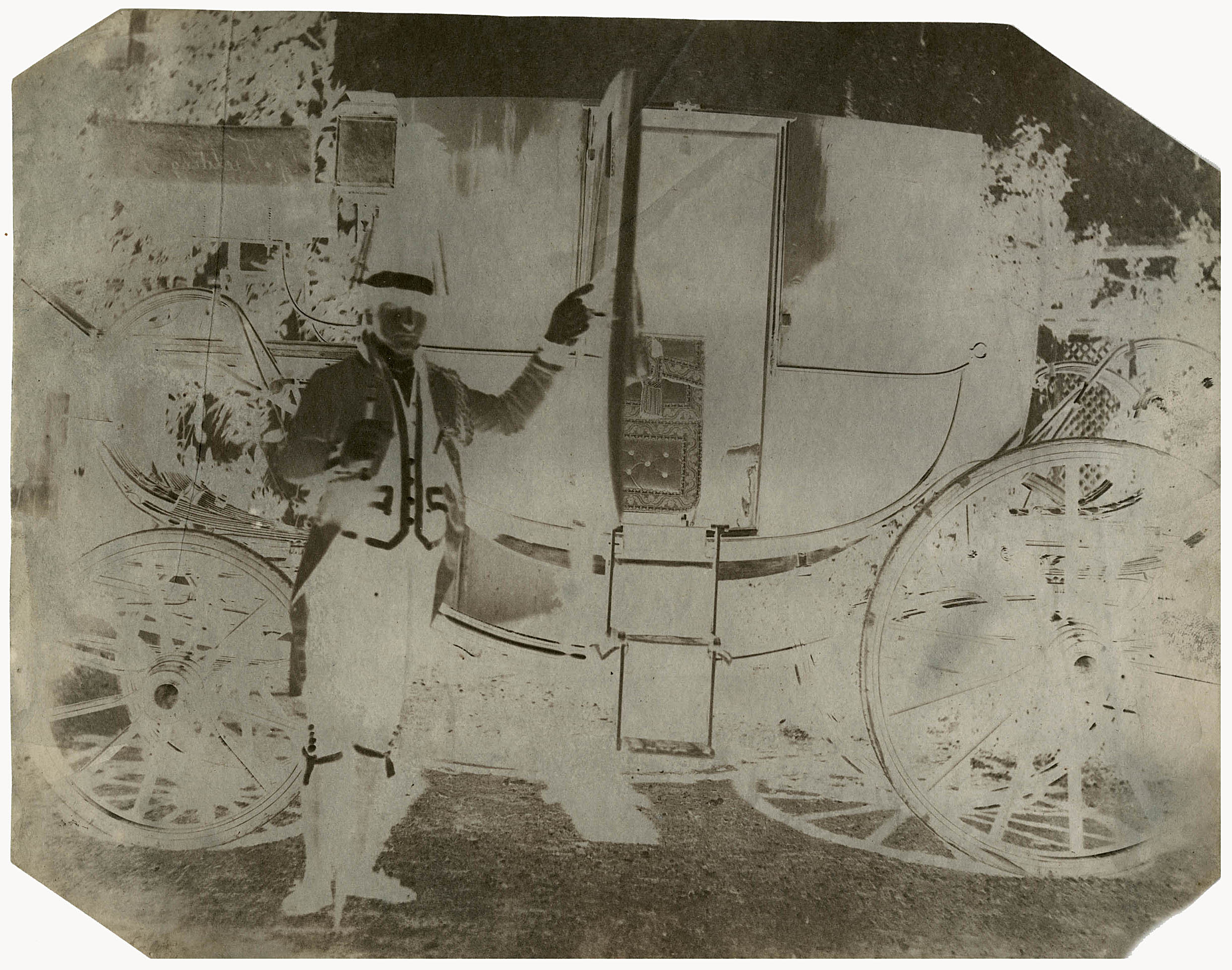

In dispatching a new group of photographs to his friend Sir John Herschel in the Spring of 1841, Talbot modestly boasted that “the footman opening the carriage door is also a good likeness, done in 3 minutes sunshine.” Herschel received a print from a splendid negative that Talbot had taken on 14 October 1840. Accomplished just a fortnight after he discovered his calotype negative process, it is only the second portrait that Talbot is known to have made, the first being a more conventional snapshot of his wife Constance. By the era of this image, footmen had become more of a status symbol than a necessity. Roads and carriage suspensions had improved to the point where the footman could ride on the outside rear step, ready to jump down at a moment’s notice to provide services along the route and to make arrangements as the coach approached its destination. At home, they polished the silver and ran errands. In January 1840, by command of Her Majesty, Talbot had been appointed Sheriff of Wiltshire, obligating him to obtain livery for his servants mirroring his new station in life. Ever the demanding supporter, his mother Lady Elisabeth guided her son into outfitting his staff properly. The reliable New Bond Street tailoring firm of G. & H. Fletcher was promptly engaged. She was proud of her work: “I have just seen your two footmen dressed & paraded in their new Liveries, which look extremely handsome. Everything is now settled, except the hats, which I think should be round with silver cords like the Duke of Devonshire’s – and will order them so if you please.”

In this striking portrait, we become the passenger, about to step into the gilt-trimmed and highly polished coach. We are welcomed by the footman, one hand upraised in invitation, the other holding open the door. Talbot gave this negative three minutes exposure in what is obviously bright sunlight. Why, when he was just then marveling at achieving exposures in seconds? In order to achieve uniform sharpness throughout the depth of the coach interior, sharply defining the taffeta and tempting our eye inwards, he would have had to ‘stop down’ his lens to a small aperture, correspondingly extending the exposure time. The surprisingly life-like stance of the footman contradicts what we expect of early photographic portraits, often with the victim’s head clamped in by an iron stand. Cleverly, Talbot employed the conceit of having his subject grasp the door and turn his feet out to form a solid human stand. Perhaps it was a well-practiced pose for footmen accustomed to their masters dawdling along the way to their carriage.

Where was the photograph taken? Although the background is ambiguous, it must have been taken at Lacock Abbey. The surviving correspondence is thin during this period, but fortunately Talbot started maintaining a detailed list of his negatives, establishing that he used his newly discovered calotype process at home throughout the month of October. Who is the subject? While no footman is specifically listed in the 1841 census for Lacock, the manservant James Wright seems to have filled this role. Indeed, he took an active interest, pressing Talbot for decisions: “will you be so good to send me if you will have Black Silk of Worsted Stockings for the Footman’s there will be a Silver Band at the Knee of the Breeches and of course Black Silk stocking will look the best, Lady Elisabeth told me she had written to you to know if you have settled to have cocked or Plain Hats,” pointing out that the former would be more expensive. However, this type of carriage was best suited to town life and it most likely belonged to Talbot’s parents, normally stabled at their Sackville Street residence in London and put on loan to the newly appointed Sheriff of Wiltshire. Maybe our subject was Lady Elisabeth’s servant?

None of the seven known surviving prints is any longer in robust condition. It was, and is, a fabulous photograph and these prints would have been examined and displayed with frequency in their day. The present print, formerly in the collection of André Jammes, is arguably the best of the lot, printed on paper carrying the watermark of ‘J Whatman Turkey Mill 1839.’

Exploiting the marvels of digital enhancement, we can bring the print closer to what Talbot contemporaries must have experienced. With the detail restored, the driver’s box displays the name of Fielding and one wonders why Lady Elisabeth Feilding would have tolerated this mis-spelling. Was it a hasty identification added for purposes of this photograph, perhaps by Nicolaas Henneman, who probably assisted in its taking but whose largely phonetic spelling of English reflected his Dutch birth?

The waxed calotype negative is inscribed by Talbot in pencil on verso: “Oct. 14 1840” and “3′ ”. In Talbot’s manuscript negative list it is described as “footman (2) at carriage door 3′ (large)”, the large referring to its 16.3 x 21.0 cm. size. The “(2)” must mean that there was more than one attempt, but the other two known images made that day are of Lacock but not of the footman. For an early experiment that was repeatedly printed, the negative itself is now in a very strong visual state, having been re-developed by Harold White around 1950. While such an invasive treatment is anathema to the conservation community today, White’s action must be considered in the context of his own period. Talbots had little or no commercial value and the idea of being able to retrieve a lost image was compelling. White noted that this negative had originally “been fixed in potassium iodide” but “had bleached.” The remaining silver iodide created by this fixing would lighten on exposure to light – the image was still there but had become invisible to our eye. Harold White took the original inventor as his guide, saying that his work on the negative caused it to be “revived as recommended by Talbot.” During the September days when Talbot was discovering the calotype, he termed his gallic acid developer an ‘exciting liquid’ (not from the thrill that it gave it him, but rather from its ability to coax action where none had been before) and recorded in his notebook that “the same exciting liquid restores or revives old pictures on … papers which have worn out, or become too faint to give any more copies. Altho’ they are apparently reduced to the state of yellow iodide silver of uniform tint, yet there is really a difference & a kind of latent picture which may then be brought out.” Talbot’s gallic acid solution was a ‘physical developer’, where the silver necessary to re-form the image was supplied from this outside solution. Working a century later, White used what is now termed a ‘chemical developer’, where the silver that forms the image is drawn from the original negative itself. White would have reached for the nearest shelf in his darkroom, employing one of the same standard metol-quinone developers he used daily for modern films and papers.

Aside from tampering with the integrity of the originals, all sorts of things can (and do) go wrong in trying to chemically restore early photographs. But however one views White’s conservation practices today, there is little doubt that he was happily successful in this case. After 65 or 70 years, the re-developed negative remains robust and visually inspiring. It would make great prints yet today (if only those dour conservators would grant us absolution). And looking at the negative and the teasingly subtle details of the prints, we can easily see why Talbot was so proud of this pioneering photograph and so untypically willing to dispatch a print with great pride to his scientific friend Sir John Herschel.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk •WHFT, The Footman, salt print from a calotype negative, 14 October 1840; the Wm. B. Becker Collection; Schaaf 2507. •WHFT to Herschel, 18 March 1841. The Royal Society of London, HS17:305; Talbot Correspondence Document no 04218. Herschel’s print, substantially faded, is in the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin, 964:054:006. • Elisabeth Feilding to WHFT, 22 February 1840; Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London; Doc. no. 04039. •The manuscript negative list covers the period of 11 December 1839 to 25 October 1840; Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London. The endpapers of my The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2000) reproduce four of the pages. •J Wright to WHFT, 15 February 1840, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London; Doc. no. 04032. •WHFT, The Footman, calotype negative, 14 October 1840; re-developed by Harold White, Harold White Collection, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 2507. A more full story of White’s interventions is in my Sun Pictures Catalogue Three: The Harold White Collection of Works by William Henry Fox Talbot (New York: Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, 1987). • On 23 September 1840, WHFT recorded an exciting liquid composed of silver nitrate, acetic acid and gallic acid; see my Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), Q41.