Recently we talked about a ‘newly-discovered’ Talbot that had turned up unexpectedly in a German auction of the estate of a camera collector. Upon further scrutiny it proved to be a previously known example that had dropped out of sight years ago – it was critically linked to Charles Babbage and remains an important re-discovery. Today I want to turn our attention to another unexpected find, this time improbably in a London auction of atlases and maps. An album containing two early Talbots was sold earlier this week at Sotheby’s.

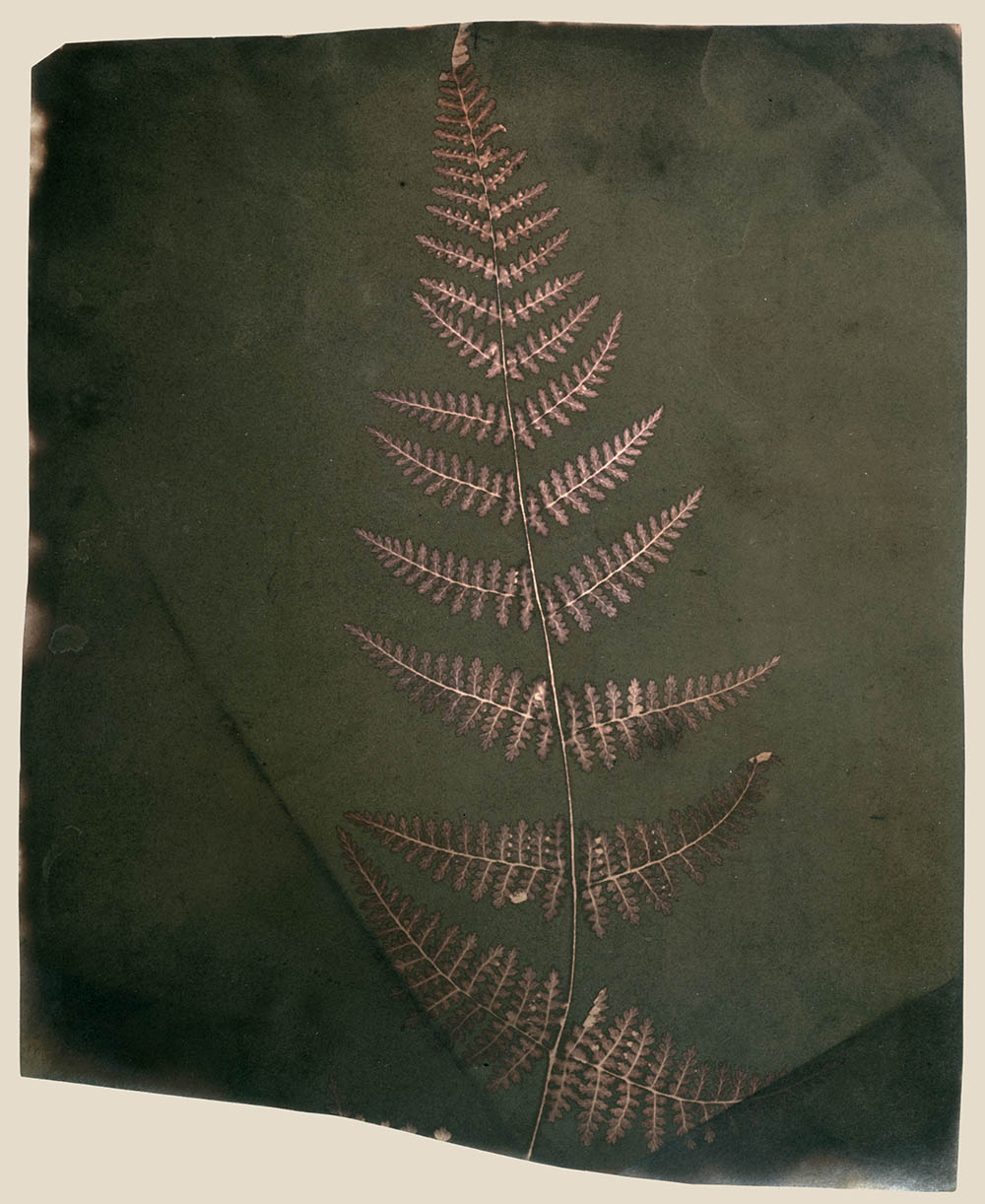

The album is a rare survivor from the collections of the Mundys of Markeaton – the family of Talbot’s wife Constance. Virtually everything about the Mundy family has been lost (including their home of Markeaton) so just the existence of this album is significant in itself. While composed mostly of watercolours and drawings by various family members, the star of the show was a beautiful photogenic drawing negative by Talbot.

The fern negative is undated but the other photograph in the album, a copy of a print, was initialed by Henry and clearly dated ‘1839’. This print has its own story but we’ll need to save that for a future blog.

Although it is clear from the contents that the album spent its life in the Mundy parlour room, there is only a hint at its major compiler. The ‘E.M’ on the pastedown is surely Constance’s unmarried sister Emily Mundy, four years her senior. Nothing is known at present of the provenance of the album nor how it managed to outlive its peers.

We know very little about Emily – there is not a single identified letter between her and Henry – but she is mentioned frequently in the correspondence. Now, another already promised future blog is about Talbot’s presentation at the 1839 British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Birmingham. It took place in early August and Henry Talbot was put in the awkward position of having to explain Daguerre’s newly-divulged process to the large assembly of scientists. He was the person best positioned to take on this task at short notice but it could not have been easy for him. On 26 August 1839, writing from Lacock Abbey, Constance forwarded some letters to her husband “& also the Literary Gazette which I thought you might wish to see as soon as possible on account of M. Daguerre’s disclosure.- I am impatient to know what you think of it.” She had received Henry’s letter from London “& one from my Sisters the same day – I was delighted with you for going so kindly, to see them & returning with the Drawings too! – Let me hear from you when you have time, & tell me whether the people have received you well.” When in London, her sisters Laura, Emily and Marian lived at the Mundy house at 44 Queen Anne Street; sometimes Henry stayed there when his mother’s house at 31 Sackville Street was not available.

I think that the ‘Drawings’ were in fact photogenic drawings. Talbot had made a large display of them at the BAAS meeting. Afterwards he had given some to his childhood friend, Sir Walter Trevelyan, but undoubtedly had others along with him. I’m going to go out on a limb to speculate that what he showed the Mundy sisters upon his return was some of the same photographs that he had just exhibited. Now, since I am drifting a bit into the realm of speculation, may I offer up the further suggestion that the two photographs in Emily’s album were part of this group? The 1839 dating on the print is suggestive and there is another factor. Just three months later, on 5 November 1839, Emily Mundy succumbed to illness and died. Of course it was common practice for surviving family members to continue to add items to albums – at least one of the drawings in the album is dated 1844 – but I think that it is entirely possible that in those three months Emily herself mounted the recently-received photographs.

Part of what excites me about this discovery is that it adds to growing number examples of this particular overworked branch of a Buckler fern. Patroclus is still safely on his throne as being one of Talbot’s most frequently photographed subjects, but this Buckler fern is starting to provide some competition. Don’t take the comparative colour balance and densities of the thumbnails below too literally, but a quick query to my database asking about ‘Buckler’ now produces nineteen hits, including this new one. You can readily see the wide range of colours and exotic trimmings in these examples, including lateral reversal, along with the degradation of the plant as leaves dropped off.

What was it about this particular fern that intrigued Talbot so much? And just what do we know about it? There are numerous types of Buckler ferns but we know from Talbot’s inscription on the example given to Dr Joseph Hamel that he considered this to be a South American specimen. On 27 February 1833, Talbot wrote to William Jackson Hooker, then the Regius Professor of Botany at Glasgow and later the Director of Kew Gardens, saying that “I possess a small collection of S. American ferns bought at an auction. I would be much obliged to you to name them for me.” Hooker was happy to undertake this task for his old botanical friend. He then gently turned down the offer of a present of one of these specimens: “because I do not like to rob you of a scarce plant, nor to break up any portion of your very nice collection of Brazilian species.”

In spite of his fondness for his fern collection, I suspect that this frond had no particular significance to Talbot when used for photographic purposes. In its dried state it was of a convenient size for his photographic paper, it was flat enough for contact printing (photograms), reasonably sturdy (seeing as how well it stood up to repeated handling) and perhaps most of all, it was at once a bold and striking visual that could demonstrate Nature’s ability to draw complex and subtly detailed forms.

Of the nineteen examples traced so far, sixteen are photogenic drawing negatives made by contact. Two of these were printed, one of them twice. Some of them were inscribed with a date by Talbot. There is an 1839, an April 1839, a 6 March and a 28 March (no year specified) and one that we know was sent in June 1839. From these I think that it is pretty safe to assume that all the examples date from March and April 1839. One carries a watermark of ‘J Whatman 1835’ and three are watermarked ‘J Whatman Turkey Mill 1838.’

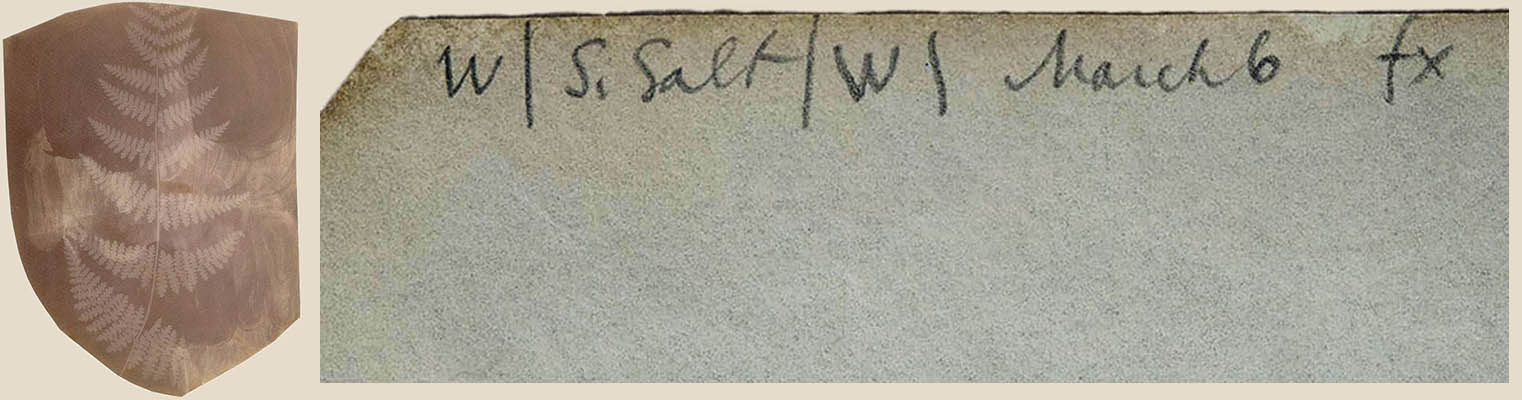

Some of the examples have other inscriptions – perhaps the most tantalizing is on the verso of a Buckler negative in the collection of the renowned photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto (Schaaf 2227).

Trimmed to almost a medallion shape, this negative carries a pencil inscription on the verso:

Trimmed to almost a medallion shape, this negative carries a pencil inscription on the verso:

“W / S. Salt / W / March 6 fx”

As mentioned before, I think that we can safely assign the 6 March date to 1839, making this the earliest positively dated one of the series (underscored by the pristine condition of the branch). Sadly, but not surprisingly, there is not a specific entry in Talbot’s research for this date. So, starting with an easy one, ‘S. Salt’ would have referred to ‘strong salt’, a saturated solution of common table salt. Still trying to perfect his fixing (in modern terms, stabilization), on 3 March 1839 Talbot made a note to “try the same with saturated salt instead of iodide potassium” – this is likely a practical test of that thought. The ‘W’ is more problematic. It could refer to the experimental sensitive paper he named after Waterloo (French competition anyone?); we know that he was working with this in 1840 but he might well have started on it earlier. However, why repeat the ‘W’ either side of the ‘S. Salt’ ? This immediately suggests an abbreviation for ‘washed’ or ‘washing’, something that would make sense in a sequence. After exposure, wash the paper, then stabilize it in a solution of saturated salt, and then wash it again. Complicating this is the ‘fx’ at the end of the string. Surely this meant ‘fixed’ – was he noting success, or recording an additional stage of chemical treatment?

Another example with a challenging inscription is in the William Talbott Hillman Collection (Schaaf 154). It is inscribed on verso in ink ‘A.B. post.’ Further complicating matters is that it is in ink rather than pencil and is in clearly a 19th century hand but I am not sure Talbot’s – certainly not his most common one. Now, what does that mean? One could jump to the conclusion that it was the initials of Antonio Bertoloni, the Italian botanist whose fine collection of Talbot photographs is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. But while Bertoloni was the recipient of one of these Bucklers (Schaaf 2259), there is no evidence that he ever took part in their production. Another possibility is suggested by a 4 December 1839 letter from Sir John Herschel to Talbot, suggesting a process “which I think may be of great service to travellers under conceivable circumstances – viz. that in place of fixing the photograph on the spot it may be by a certain application A totally obliterated instanter – And after remaining as white paper in his portfolio, or exposed to air and sun ad libitum [at liberty] for an indefinite time – the image may be recalled in an instant and fixed by a brushing it over with another liquid B. – I have some idea that two images may be made to coexist on the same paper both invisible and either of which may be thus recalled at pleasure without the other, but I have not yet satisfied myself of its practicability.” Perhaps the ‘post.’ is a contraction of postremo, ie next or following, which would make sense for a sequential process like this?

The ‘A.B. post.’ appears on the verso of two other Talbots, a negative of flowers and grasses at the NMeM (Schaaf 2261) and a lovely fan of leaves in the Smithsonian (Schaaf 2304), illustrated above, where the additional step of nitrate of mercury has been noted.

The ‘A.B. post.’ appears on the verso of two other Talbots, a negative of flowers and grasses at the NMeM (Schaaf 2261) and a lovely fan of leaves in the Smithsonian (Schaaf 2304), illustrated above, where the additional step of nitrate of mercury has been noted.

A final possible explanation comes from Talbot’s notebook Lacock June 1838, which carries on into 1839 and is one of our best – and most enigmatic – sources for his actions in the first public year of photography. There is a lot of back and forth in this notebook, but seemingly in January he recorded that ‘ab’ meant ‘not preserved’, in other words, not fixed. The complex and intriguing greenish/reddish tones of this negative are typical of what might expect in a carefully kept nearly 175 year old negative. Arguing against this is Talbot’s use of lower case ‘ab’ here and deliberately capitalised ‘AB’ on the photographs.

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • WHFT, Buckler Fern, photogenic drawing negative, March/April 1839, Private Collection; Schaaf 5553. • Constance Talbot to WHFT, 26 August 1839, Talbot Correspondence Document no. 03924. • WHFT to William Jackson Hooker, 27 February 1833, Document no. 02613. • Hooker to WHFT, 15 June 1833, Document no. 02713. • Henry’s delightfully scattershot research notebooks can be read in my annotated facsimile: Records of the Dawn of Photography: Talbot’s Notebooks P & Q (Cambridge University Press, 1996). • Herschel to WHFT, 4 December 1839, Document no. 03982. • WHFT, Branch of Leaves of Mercurialis perennis, photogenic drawing negative, 14 July 1839. Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 1995.0206.029; Schaaf 2304. The recto of this lovely image is plate 29 in my Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton, 2000). • WHFT, Lacock June 1838, memoranda notebook, Fox Talbot Collection, The British Library, London. • Mark Lehner is quoted from Alexander Stille’s The Future of the Past (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002). If this book is not on your shelf, may I suggest that it should be.