Good news! Earlier in the week I reluctantly reported that The Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot was having major indigestion. I am happy to say that thanks to the efforts of De Montfort’s staff, the site is functional once again. And thanks to our readers for your patience and interest. Please report any future problems to me – it is always possible that other vexations may arise as DMU changes its servers and its software evolves. Although I am just as dependent on the online structure as anyone else, I’ll be happy to try to assist researchers on an interim basis if I can reconstruct the information from my personal files.

Today we shall try to put a little bit of clothing on a ghost

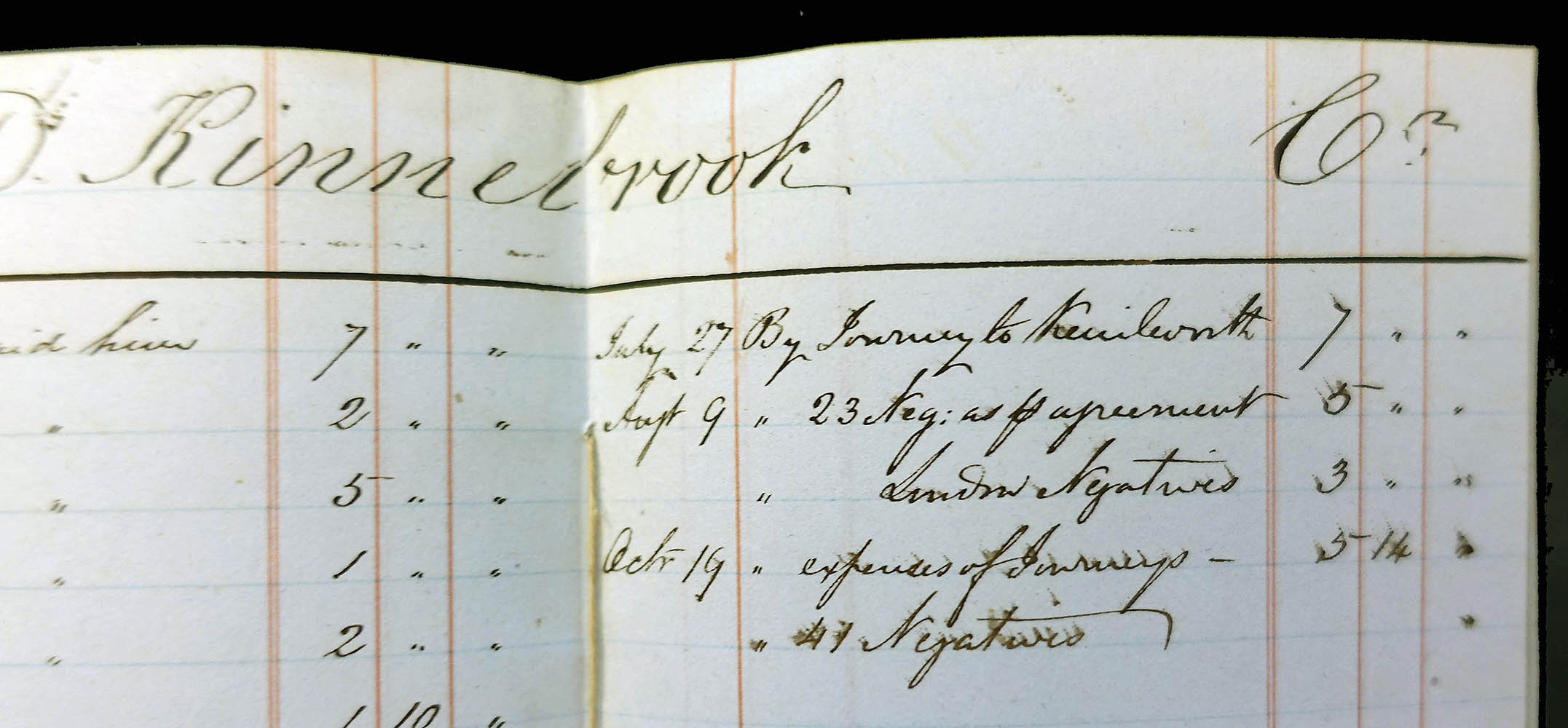

Within the Talbot oeuvre, there is a distinctive group of images that has always particularly intrigued me. It is a set of photographs clearly not in Talbot’s normal style nor do they match the known formats of his cameras. They measure roughly 18.5 x 14.5 cm (vertical and horizontal), falling between Talbot’s typical larger and smaller formats. Visually, they bear such a strong resemblance to each other that they must be the work of one photographer. So far I have corralled together 168 artifacts representing 88 unique images, including 61 negatives. Since many of them were taken in Norfolk, the late Cliff Middleton expressed the opinion that they might be by Thomas Damont Eaton (1800-1871), a calotypist and President of the Norwich Photographic Society. After examining the large body of Eaton’s work preserved by his descendants and later donated to the Norwich Public Library it became clear to me that these were not by Eaton. The expert on Norfolk photography, John ‘Ben’ Benjafield, recently agreed.

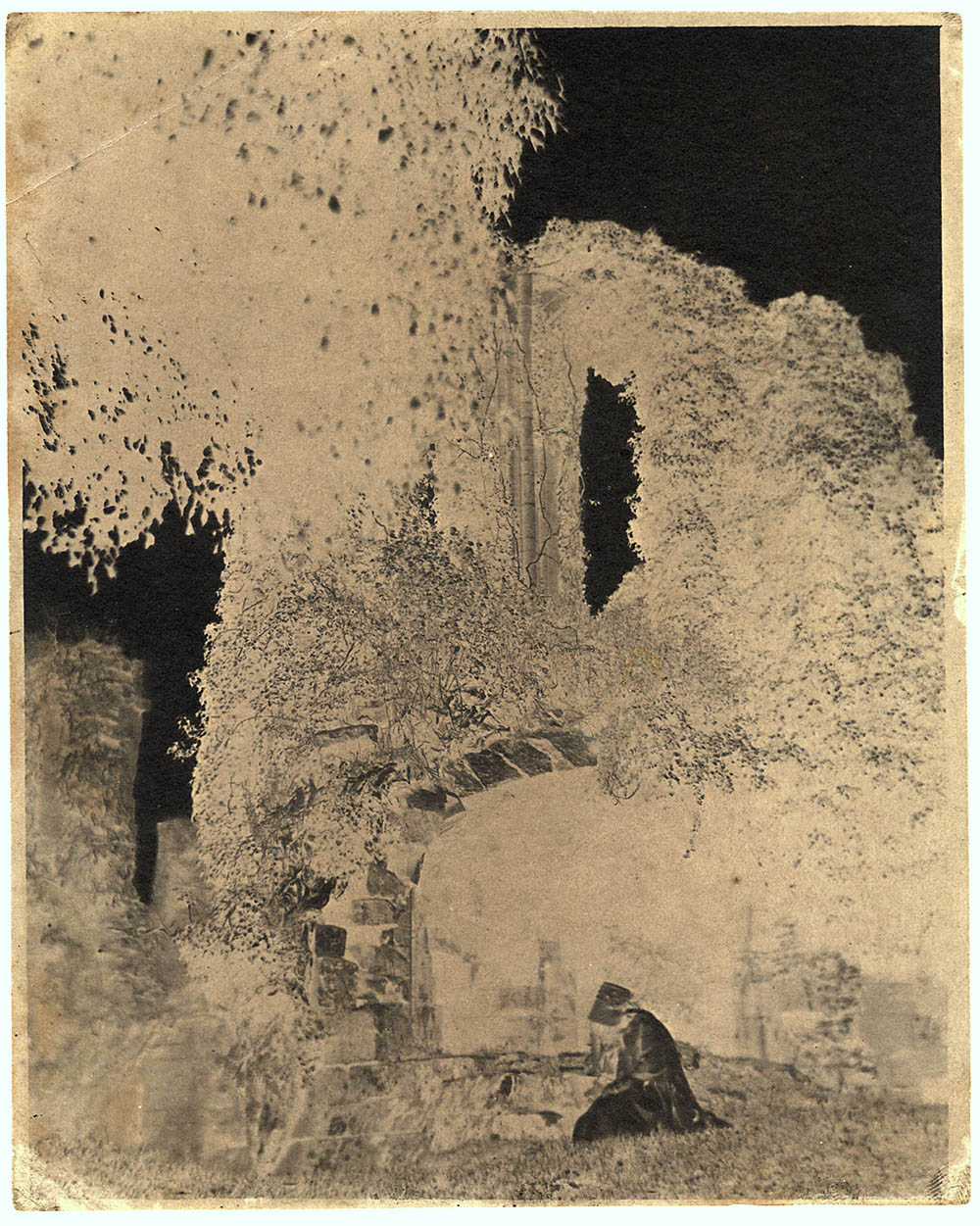

So who did take these calotypes? The photographer of this negative very kindly left us a little physical clue, a pretty clear thumbprint imparted when the negative was being processed. Sir John Herschel’s son William James was the first to apply fingerprints for identification, but unfortunately lacking any verified database of the fingerprints of Talbot and his circle, this clue remains a tantalizing part of the mystery.

These images are included in the Catalogue Raisonné because they have traditionally been linked with Talbot, indeed, often published as being his work. When and how did these photographs enter Lacock Abbey? The latter question is a complicated one. Just because photographs were found in the Abbey after Talbot’s death does not prove that he even saw them. The late Anthony Burnett-Brown, his great-grandson, once told me about him returning from national service and opening packets that had come from Nicolaas Henneman in London more than a century before in the 1850s. Talbot had accepted some of Henneman’s stock as partial repayment of debts and had never even opened some of them. Many of these images went to the Science Museum in Matilda Talbot’s massive 1934 donation. On one of my visits in the late 1970s, Dr David Thomas told me about a practice that he and quite probably his predecessors followed. When unidentified early photographs were discovered elsewhere in the Science Museum collections, or came in by donation, they were often filed in the Talbot boxes – a logical and convenient practice. However, Matilda Talbot’s collection was not fully inventoried until the 1990s (the makings of a future blog) so in many cases there is no real way of knowing if what was inventoried actually came from her.

But today’s group of photographs can mostly be traced back to the Lacock Abbey collection. Did Talbot ever see them? Happily there is evidence that he did.

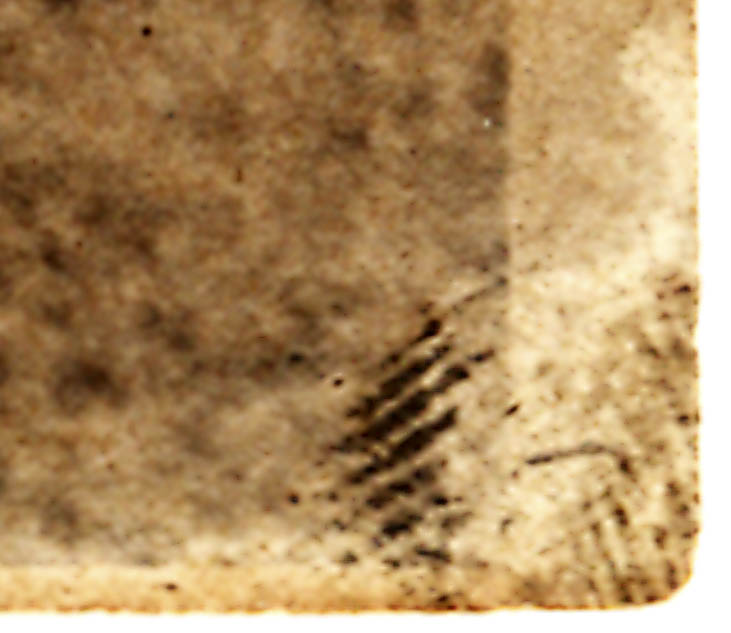

When Henneman’s operation at Reading was being transferred to London in 1846-1847, Talbot took on more financial liability and started requiring more detailed accounting. The 1847 sheet for ‘D. Kinnebrook’ lists payment on 27 July for a journey to Kenilworth, then on 9 September the acquisition of 23 negatives ‘per agreement’ as well as some London negatives. On 19 October further travelling expenses are paid and an additional 47 negatives were acquired. Henneman’s financial records survive only in fragments so there may well have been other activity and additional payments.

There are other mentions of Kinnebrook in various other Talbot documents, a payment on the left below, a question in Talbot’s own hand on the right whether an Olney Church picture was supplied by him.

Kinnebrook is an unusual surname but I am still going out a bit on a limb here in declaring that I think that I may have snared the right one. But as my friend Martin Kemp famously says, if you are going to fail you might as well fail spectacularly. Hopefully this is not a house of cards.

David Kinnebrook was born in 1819 in Norwich into a publishing family. His uncle, also David, was a famous astronomer’s assistant to the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne. It is just possible that his relative Nevil Story Maskelyne was the one who introduced the nephew to Talbot. At present, we know virtually nothing about Kinnebrook’s time in Norwich except that he was involved in the family publishing business with his older brother William and a partner by the name of Bacon. In addition to publishing books and a newspaper, they sold stationary supplies and patent medicines. Perhaps David was able to obtain chemicals and paper through his business? In 1840, his firm published the Companion to the Norwich Polytechnic Exhibition, a show that featured daguerreotypes and photogenic drawings, so he might have seen his first photographs there. In the 1841 census David listed his occupation as ‘Independent Means’ and by June 1847 he legally withdrew from the partnership.

Most of what I know at this point about David is through the legal records of his family members. In early 1848 he married Rebecca Leighton, also a Norwich native, in Bedminster, Somerset. Why he was in the Bristol area is at present unknown but whilst there he might well have come into contact with the Rev Calvert R Jones. Lacock is not very far away. It was more than a brief visit, for the couple’s first son was baptized in Bristol in May 1848. In early 1850, their second son was baptized in Norwich, as were subsequent children, so they must have moved back home.

In May 1853 a “brick and slate dwelling house, on Windsor Place at Lakenham, in the occupation of Mr David Kinnebrook” was sold at auction. David and Rebecca apparently continued to live in the area, for four more children were baptized there. Not unusually for the period, there was a high infant mortality rate among their children. In June 1858 another son was born in Norwich but he died within months.

Almost immediately came a huge change. David, Rebecca and their four surviving children boarded the Clontarf, a Canadian built clipper ship leaving Gravesend on 16 September 1858 and departing Plymouth on 20 September. The Kinnebrooks were in the second cabin, part of 28 cabin passengers; the other 349 passengers were not so lucky, being distributed between government bunks and steerage. After 105 days they arrived in Lyttleton, New Zealand on 5 January 1859.

Almost immediately came a huge change. David, Rebecca and their four surviving children boarded the Clontarf, a Canadian built clipper ship leaving Gravesend on 16 September 1858 and departing Plymouth on 20 September. The Kinnebrooks were in the second cabin, part of 28 cabin passengers; the other 349 passengers were not so lucky, being distributed between government bunks and steerage. After 105 days they arrived in Lyttleton, New Zealand on 5 January 1859.

Only a few passengers (and a number of dogs) had died during the journey, a typical attrition rate caused primarily by disease. The Clontarf’ts next voyage, however, became a notorious disaster, for 41 people perished on the journey, putting an end to its use as an immigrant ship.

The Kinnebrooks settled in an area called Woodstock, part of Oxford on the North bank of the Waimakariri River, outside Christchurch, New Zealand. Prior to their arrival they had purchased land in this remote area. For a while, David was an accountant for the local newspaper and then took up sheep farming on his own land. Ellen Mary was born there in 1862; a son born the following year died immediately. According to one account, “the Country at the head of the Woodstock was occupied by David Kinnebrook, a strange and lonely man who lived in a hut which he built just below the Broken River junction…his block was surrounded by hills, forest, a gorge and a narrow boundary line and access to it was most difficult.”

And then tragedy struck. On the 4th of July, 1865, David and his son went out to inspect their land. His son became tired so David struck out on his own, never to return. The Lyttleton Times reported on 26 July that “the country to which Mr. Kinnebrook went is described as offering a traveller without supplies little chance of supporting life” – his body was found the next day. His will left everything to Rebecca. Pregnant once again, she bore her dead husband’s son on 16 October, but what happened after that is again unclear. In 1869, the Royal Asylum of St Anne’s Society in London took in Ellen Mary Kinnebrook, the daughter born in New Zealand in 1862 – they afforded “a home, clothing, maintenance, and education, to children of those who have once moved in a superior station of life, orphans or not.” Perhaps Rebecca had sent her to England on her own, perhaps she left Ellen in New Zealand for a while, but on 3 July 1866 Rebecca left for England on the Dona Anita with just a son. This was presumably David, her eldest, who had accompanied his father on the fateful outing; he died in Derbyshire in 1873. In 1876 Rebecca was back in Norwich, listed on the Election rolls. That year she married William Hudson, a Norwich carpenter, and they last appear in the 1881 census. Ellen Mary went on to be a nurse in London. Her older sister, Alice Rebecca, who had been born in Norwich before their emigration to New Zealand, moved to the US in 1895 and was in Chicago in 1910.

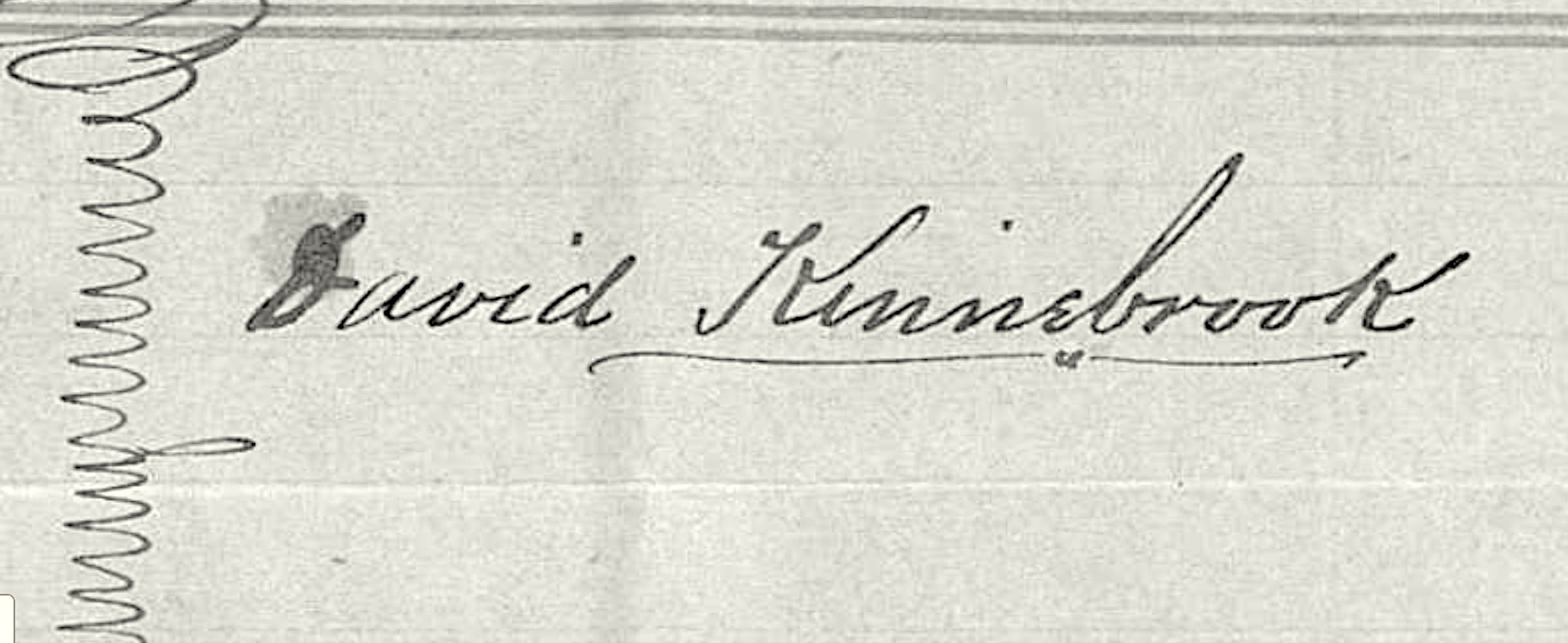

There is no known portrait of David Kinnebrook – no letters – only his signature on his will. Going from independent means in 1841 to being a highly accomplished calotypist in 1847 but then on to a rough life in New Zealand, like his daughter he indeed ‘once moved in a superior station of life.’

In order to start their field research, our more adventurous readers might want to hike into Kinnebrook’s Hut although the description makes it sound like it is a rather poshly-updated version of what the Kinnebrooks built: ” a lovely corrugated iron hut, completely lined with timber, with a wooden floor and a well designed open fireplace.”

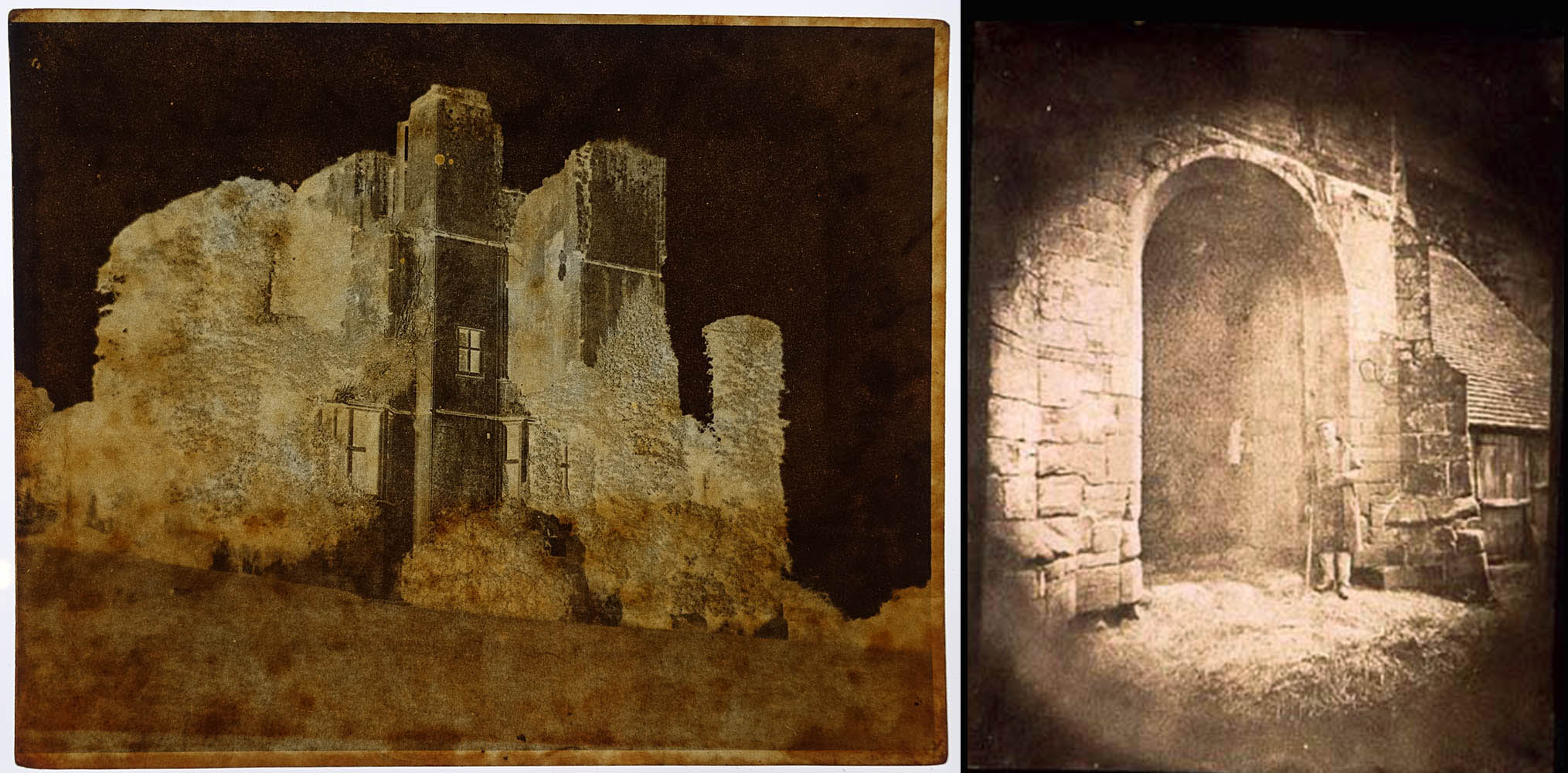

This wonderful photograph has always puzzled me, but it is easy to imagine a Kinnebrook daughter presiding over the forced sale of some of their possessions. I’ve gone into considerable detail here (admittedly of minutæ) in the hopes that others may pick up the thread and flesh out this ghost of David Kinnebrook. His photographs obviously impressed Henry Talbot and Nicolaas Henneman prepared prints from them for sale. He not only sensitively photographed the ruins in Norfolk, but his observations of the people there are an outstanding early legacy of photography. David Kinnebrook is one of the many components that make up the rich texture of the Catalogue Raisonné. And at least at present, Talbot’s archives are the only place that his photographic spirit is known to survive.

Larry J Schaaf

Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Special thanks to Adrian Andrews, the Bristol historian, for his enthusiastic encouragement. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, Lady in Abbey Ruins, calotype negative, ca. 1847; Jay McDonald Collection, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 3501. Is the woman in the photograph Rebecca, posing for her future husband during their courtship? • Henneman Account Book, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, Add MS 88942/1/302. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, Ash, from Fosse of Castle Rising, Norfolk, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1847; Talbot Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2489; Schaaf 3506. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, St Benet’s Abbey, Norfolk, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1847, courtesy of Hans P Kraus, Jr, Inc, New York; Schaaf 3537. • Henneman Account Book and List of Calvert Jones’s pictures, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, Add MS 88942/1/290 and Add MS 88942/1/349. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, The Gamekeeper, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1847, formerly in the collection of Nevil Story-Maskelyne, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Schaaf 3516. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, Leicester Buildings, Kenilworth Castle, calotype negative, ca. 1847, Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford; Schaaf 3510. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, Man with Walking Stick, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1847, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, LA519; Schaaf 4402. • Although the Kinnebrooks are not mentioned specifically, an idea of the horrors of their journey can be found in Marolyn Diver, The Voyages Of The Clontarf (Dornie Publishing, 2011). • The quote is from D. N. Hawkins, Beyond the Waimakariri, a Regional History (Christchurch: Whitecombe and Tombs, 1957), p. 174. • Attributed to David Kinnebrook, Girl and Possessions, Castle Rising, Norfolk, salt print from a calotype negative, ca. 1847, Photographic History Collection, Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 67.172.2; Schaaf 3520.