Writing from Cowes on the Isle of Wight in the autumn of 1835, Talbot’s wife Constance described taking advantage of the bright moonlight to go rowing on the estuary of the River Medina: “The colouring reminded me a good deal of some of your shadows … I wish you could have taken the outline of the castle & fine elms behind just as I saw them.” This followed on from the ‘glorious summer’ of 1835, when Talbot had built on his original successes in the spring of 1834 and had started to make more sophisticated photographs. Like all his early work, these were negatives – ‘shadows’ as Constance imagined them. She went on to ask, “Shall you take any of your mousetraps with you into Wales? – it would be charming for you to bring home some views.” And thus ‘mousetraps’ entered the vocabulary of photography. As far as I know, this is the one and only time Talbot’s little homemade cameras were called that, but it is such a lovely and evocative term that historians just cannot resist. The Talbots’ first child, Ela Theresa, had been born in the spring and Constance and the toddler joined her parents in the Isle of Wight for some relaxation. Henry left separately for Wales a few days after this letter. Whether he took his mousetraps with him we do not know.

Unless you are viewing this on the small screen of a mobile phone, the above photograph will be appearing much larger than its real Lilliputian dimensions. The original is less than 5 cm. in each dimension, no larger than a commemorative postage stamp. This Grove of Trees at Lacock Abbey, from the Point of View of a Mouse was made in a ‘mousetrap’ camera, almost certainly in the summer of 1835, and its depiction of trees may well have triggered Constance’s thoughts on the elms at Cowes. It should probably be represented more like this:

Talbot had set his little camera right on the ground, pointing up at the trees, and then apparently trimmed the negative to match the natural perspective that resulted. If the shape reminds you of a tooth, perhaps it is fitting that this negative was acquired by a dentist (another dentist will enter the story in a moment).

Legend has it that the simple little wooden cameras were made by the Lacock village carpenter, Joseph Foden. In contrast to later more professionally made photographic ones, like that on the left below, Talbot’s earliest ones looked like the simple little box on the right, about the size of a good Wiltshire apple:

Talbot would have used lenses that he had for other purposes at Lacock Abbey, perhaps one for a microscope or more likely a telescope eyepiece that would have fit into the large hole in the middle of the front. But what is that smaller hole in the lower right? It is a direct response to Talbot’s first process of photogenic drawing, a print-out process where the silver image was reduced fully by the action of light. As a consequence, the negative paper had minimal sensitivity, and by removing the cork covering this little hole, Talbot could compose and focus his scene directly on the sheet of sensitized paper. At a Lacock workshop in 2012, Yoko Shiraiwa did just this using a reproduction camera:

While one can easily imagine why Constance would compare these to mousetraps, it is a little more difficult to conjure up the image of the Squire of Lacock arranging these little boxes around the grounds of the Abbey and leaving them there for perhaps half an hour, not to snare rodents but rather to trap the drawings of Nature.

In spite of intense interest, we know surprisingly little about the equipment that Talbot used. In 1905, Catherine Weed Ward visited Lacock Abbey and arranged some of the cameras that she found there out on the lawn, displaying them on the stools and small tables of the type that Talbot used for tripods:

We don’t know if these were all Henry’s cameras, or perhaps some used by his son Charles Henry Talbot, or perhaps ones used by others. But what is of most interest are the smallest ones in the front of the middle and right tables. Further confusing the situation is the inadequate record keeping of the early twentieth century, when Lacock’s cameras moved back and forth between the collections of the Science Museum, the Royal Photographic Society and more recently the National Media Museum. Mixed in with the originals are quite a number of replicas. Some are openly obvious, such as this early 1960s display item made in the workshops of the National Technical Museum in Prague:

At least thirty functioning modern replicas were made for the workshops conducted periodically at Lacock:

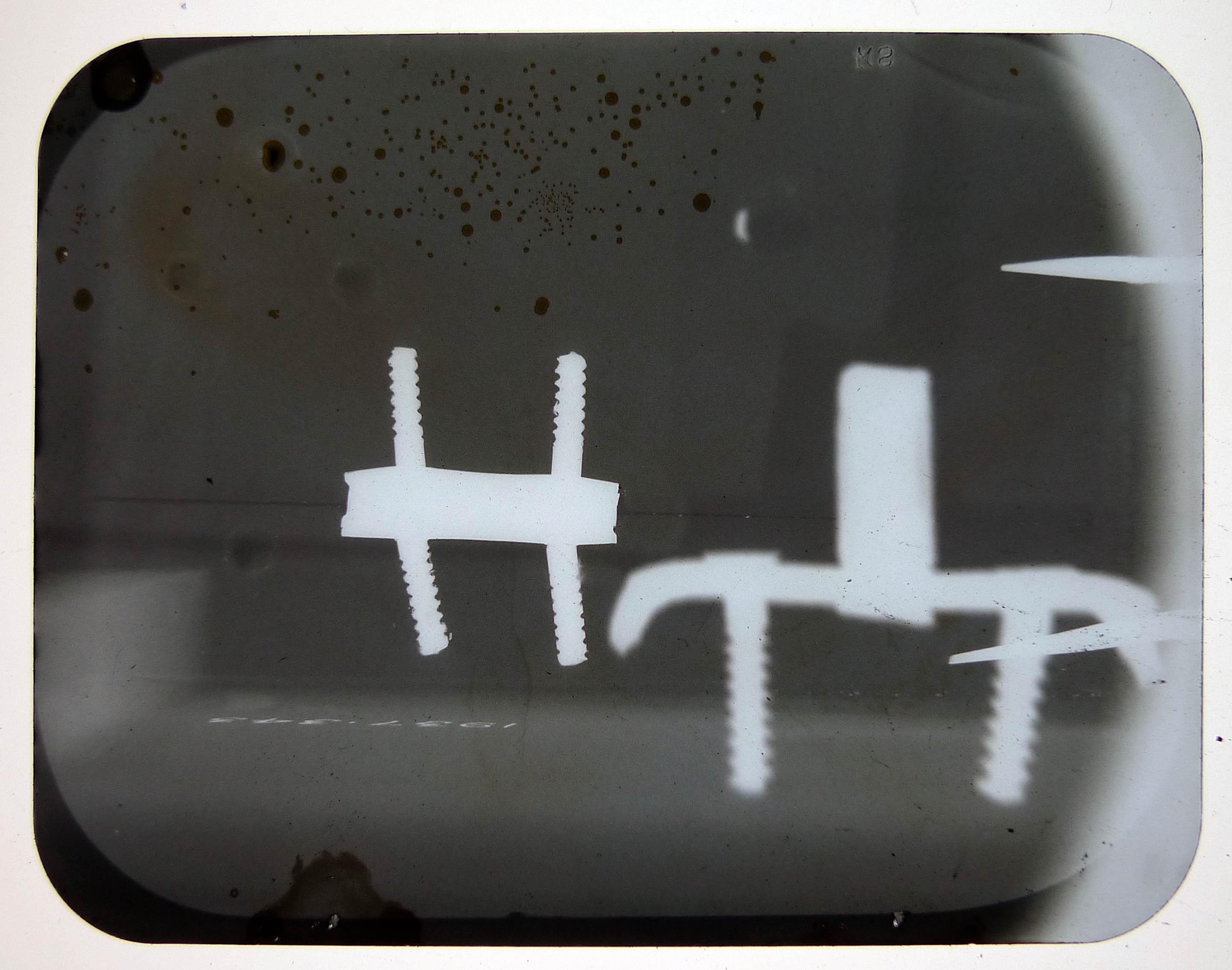

One can also find examples on ebay and in private collections. However, there is another set of replicas that are so difficult to detect that they have probably been exhibited as originals. Some years ago, Roger Taylor, Senior Curator at what was then called the National Museum of Photography, Film & Television had some suspicions and had his Bradford dentist xray some examples held by the Museum.

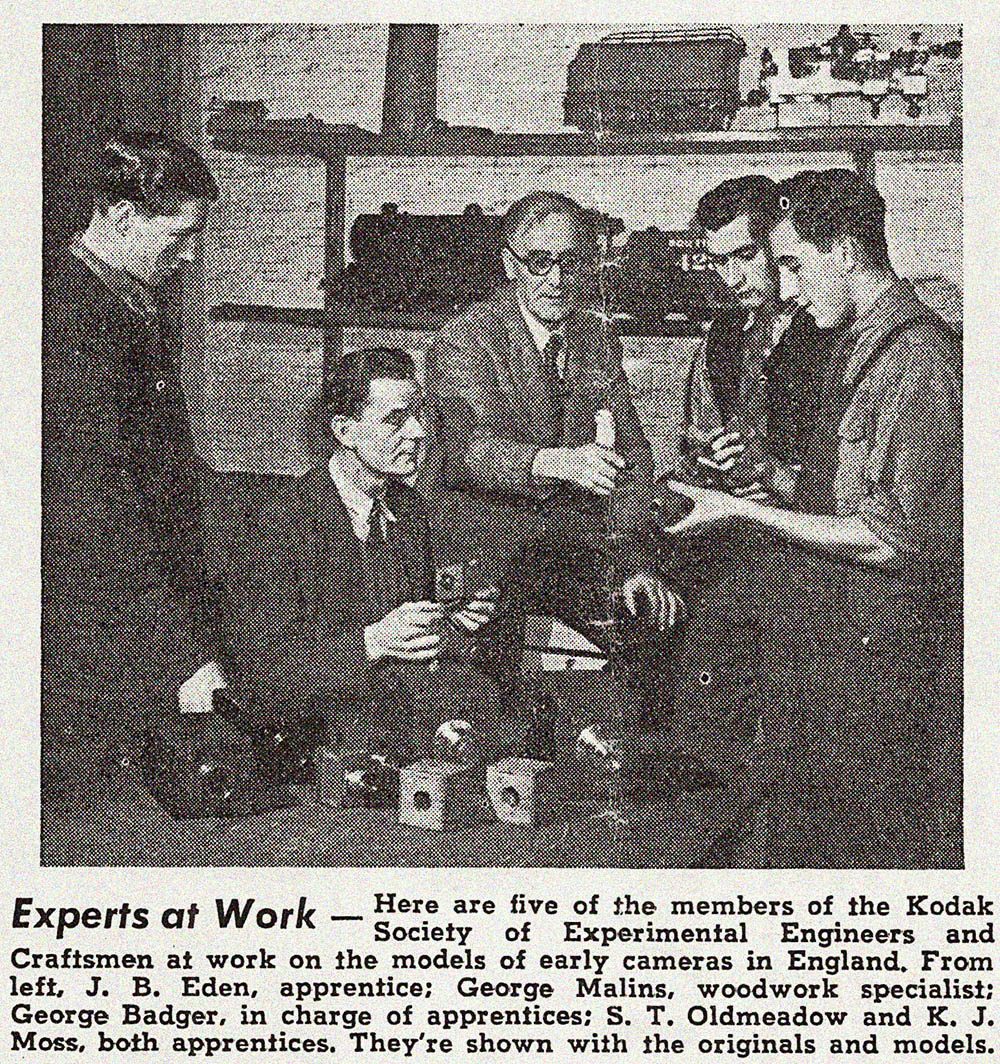

The internal presence of modern machine-made screws and pins confirmed his suspicions. Subsequent close examination by one of the Museum’s workmen revealed planer marks and other signs of modern tooling. It is not surprising that these replicas had co-existed undetected side by side with the authentic ‘mousetraps’ for so long. In Britain, immediately after WWII, there was a Kodak Society of Experimental Engineers and Craftsmen, based out of their factory in Harrow, just outside London. Dr D A Spencer of Kodak, Ltd., arranged to borrow authentic originals from the Royal Photographic Society and the craftsmen copied every detail, even down to the chemical stains left in the wood. These replicas entered variously the collections of the Kodak Museum at Harrow, the Royal Photographic Society and the Science Museum, intermixing through loans and displays.

Meantime, back in Kodak’s home of Rochester, New York, The George Eastman House Museum of Photography was chartered in 1947 and opened to the public in 1949. Among their Talbot examples is this fine photogenic drawing negative, most likely dating from the summer of 1835, depicting Sharington’s Tower at Lacock Abbey:

Nearly 12 cm. in both dimensions, it is still tiny enough for a mousetrap camera – the rough torn corners resulted from temporarily pasting the sensitive paper to the inside back of the camera. I love the exuberance of the hastily brushed chemicals, showing the two coatings essential to photogenic drawings, the solution of table salt and the second one of silver nitrate; when they interacted, light sensitive silver chloride was precipitated directly into the fibres of the paper.

Dr Walter Clark of the Kodak Research lab in Rochester, New York, was also the Chairman of the Historical Committee of the new Eastman House museum and used his company connections to enrich their collections. At the beginning of 1949, Kodak Rochester’s internal magazine, Kodakery, proudly announced:

Dr Clark had secured replicas of five different Talbot cameras. Their new curator, Beaumont Newhall, normally known for his concentration on photographic imagery, was clearly impressed with the educational and display value of these.

The team that had created the replicas had hand skills almost unimaginable in our mass electronics world of today.

Now, as promised in the title, mousetraps and two dentists have figured into this story, but what about those long rifle cartridges? Rochester was in a position to compensate its friends across the pond, but how best to do this? How did one put a price on what was obviously a group labour of love? In the draconian rationing of post-war Britain, food parcels were most welcome, and at least seven CARE packages were sent. Dr Clark wanted to supplement this with a cash payment, for he felt that the Museum was getting quite an important bargain. In the summer of 1949, a deal was reached. Originally, it was suggested that Rochester might supply the Society with useful tools and supplies, but the Kodak employees in Britain already had what they needed. Instead, they suggested that $200 worth of .22 long rifle cartridges could be sent to the Rifle Section, another Kodak Harrow factory club. The proper forms were completed and ‘Palma clean bore’ ammunition was duly dispatched to the enthusiasts.

If any readers of this blog know anything about the men who made the replicas, or indeed any other details about this story, I would very much appreciate hearing from you, for I am sure that there is much more to be discovered about this endeavour. While the Catalogue Raisonné is about Talbot’s photographic images, it is impossible to completely separate the influence of chemistry and apparatus from his vision.

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk• WHFT, Grove of Trees at Lacock Abbey, from the Point of View of a Mouse, photogenic drawing negative, summer 1835? Collection of Dr Walter Knysz, Jnr., Schaaf 944. • Letter, Constance to WHFT, Monday evening 7 September 1835; LA35-26, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London; Talbot Correspondence Document no. 03132. • Two of WHFT’s cameras (replicas or originals?) on display at the Royal Photographic Society, 1970s, photo by HJP Arnold. • WHFT, Looking Up to the Summit of Sharington’s Tower at Lacock Abbey, photogenic drawing camera negative, summer 1835? George Eastman House, 74:0047:32; Schaaf 1662. • Copies from the scarce issue of Kodakery were kindly supplied by Karl S Kabelac and Nick Graver. • Dental xray from Roger Taylor’s archives, with thanks. • Roger Watson, Curator of the Fox Talbot Museum at Lacock is one of the few people who have taken a serious interest in Talbot’s equipment and he is to be encouraged in continuing this quest. The workshops operated in conjunction with the Museum are covered periodically in their facebook page.