Last week’s Vexations of a Poet’s Heart briefly explored the close relationship between William Henry Fox Talbot and his neighbor, Thomas Moore, the radical and wildly popular Irish poet. It was not only Henry who was familiar with Moore. Indeed, the poet met Lady Elisabeth and Captain Feilding before young Talbot had attained the age of majority and were close friends thereafter. Moore and his wife Bessy were particularly fond of Henry’s younger half-sisters, Caroline Augusta (b. 1808) and Henrietta Horatia Maria (b. 1810), always known as Horatia, both who had the maiden name of Feilding.

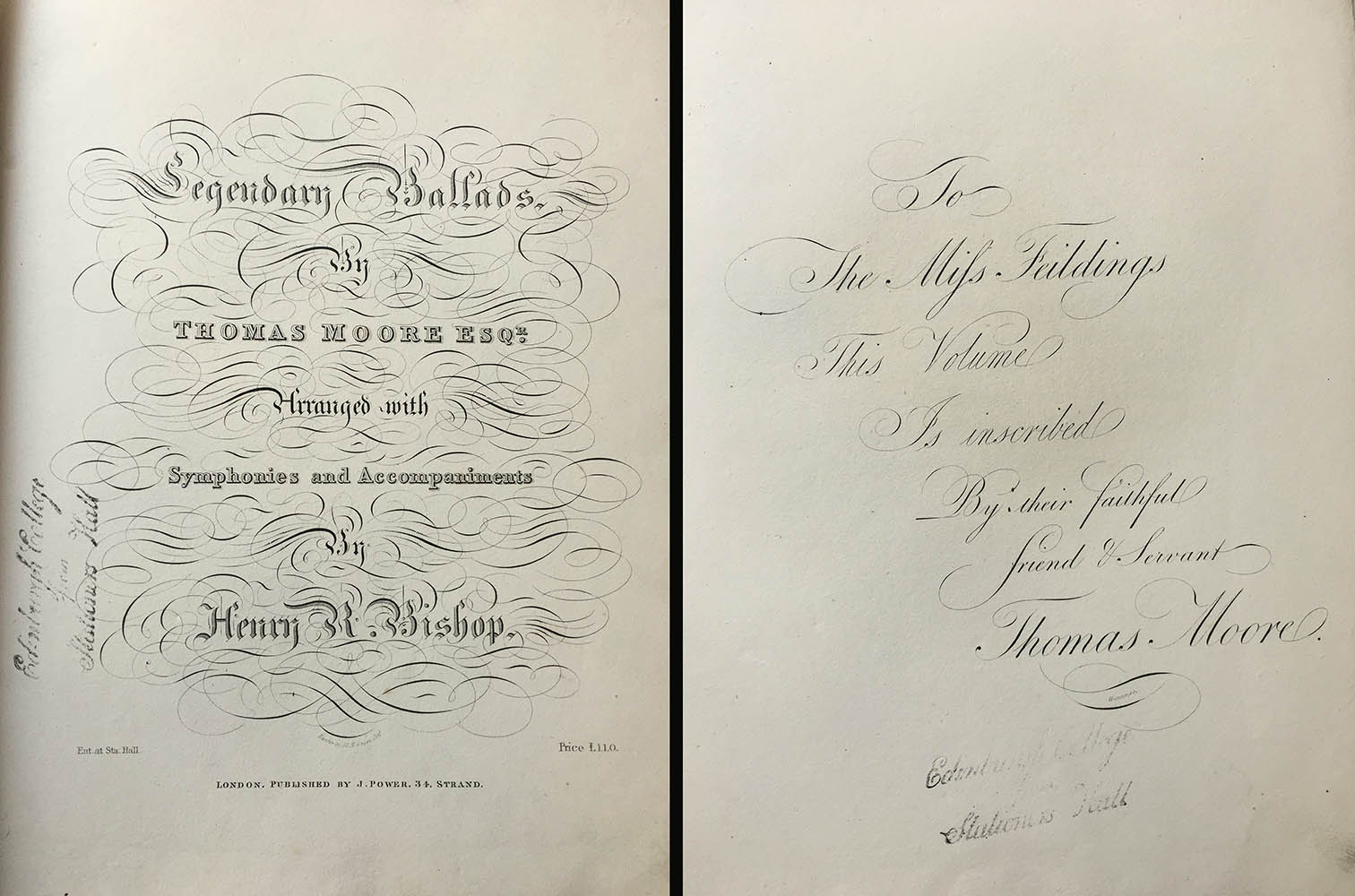

The visual link between the Talbot family and Thomas Moore started before photography. In 1828, when Moore was compiling his music for is Legendary Ballads, he knew who he wanted to illustrate them. Early in the year he recorded in his Journal that he had “induced Caroline Feilding to undertake some designs for a Volume of Legends I am about to publish.” She was apparently a bit uncertain about this important commission, for in April 1828 Moore reported to his publisher that “Miss Feilding, I find, will not let … any one see the designs till I come to town.” In August Henry Talbot wrote to Horatia: “Mr Moore was very much pleased with Caroline’s two last vignettes, the singing Lady & the voice – that is to say, the Lady carried off on horseback in the sea. The pilgrim is now engraved.” In early October, their proud mother reported that “Caroline has to day completed her twelve vignettes for Mr Moore’s Legends by the time you come back you will see her in print.”

When they were printed, the numerous illustrations were prominently labelled ‘CAF del.’, Caroline Augustus Feilding, delineavit (she drew it).

Caroline not only got credit for each illustration, but Moore additionally honoured her sister Horatia for the musical influence that she had had on the poet, generously dedicating the volume to ‘The Miss Feildings.’ Shortly after she married Ernest Augustus Edgcumbe, Lord Valletort, 3rd Earl of Mt Edgcumbe, at Lacock Abbey in January 1832 Moore wrote a poem dedicated ‘To Caroline Viscountess Valletort’ which he later published.

Don’t always believe the date on title pages: in February 1829, Moore hoped that his publisher could send a set of “proofs of the music of the Legendary Ballads that I might be able to sing it to my neighbors at Laycock Abbey.”

Surely Moore’s publication influenced Talbot’s own first book, Legendary Tales, in Verse and Prose, published two years later (along with a section titled ‘The Magic Mirror’). Lady Elisabeth felt that this effort fell far short of her son’s potential, not hesitating to “tell you my opinion (which I hold it my duty to do, because no other person stands in the same relation to you as myself) about printing. They are all very pretty in their several ways & if inserted in a Keepsake &c &c &c would each appear to be in its proper place, but would I fear disappoint expectations so highly raised as they have been about your talents, which have always justly been held to be of a very superior order.”

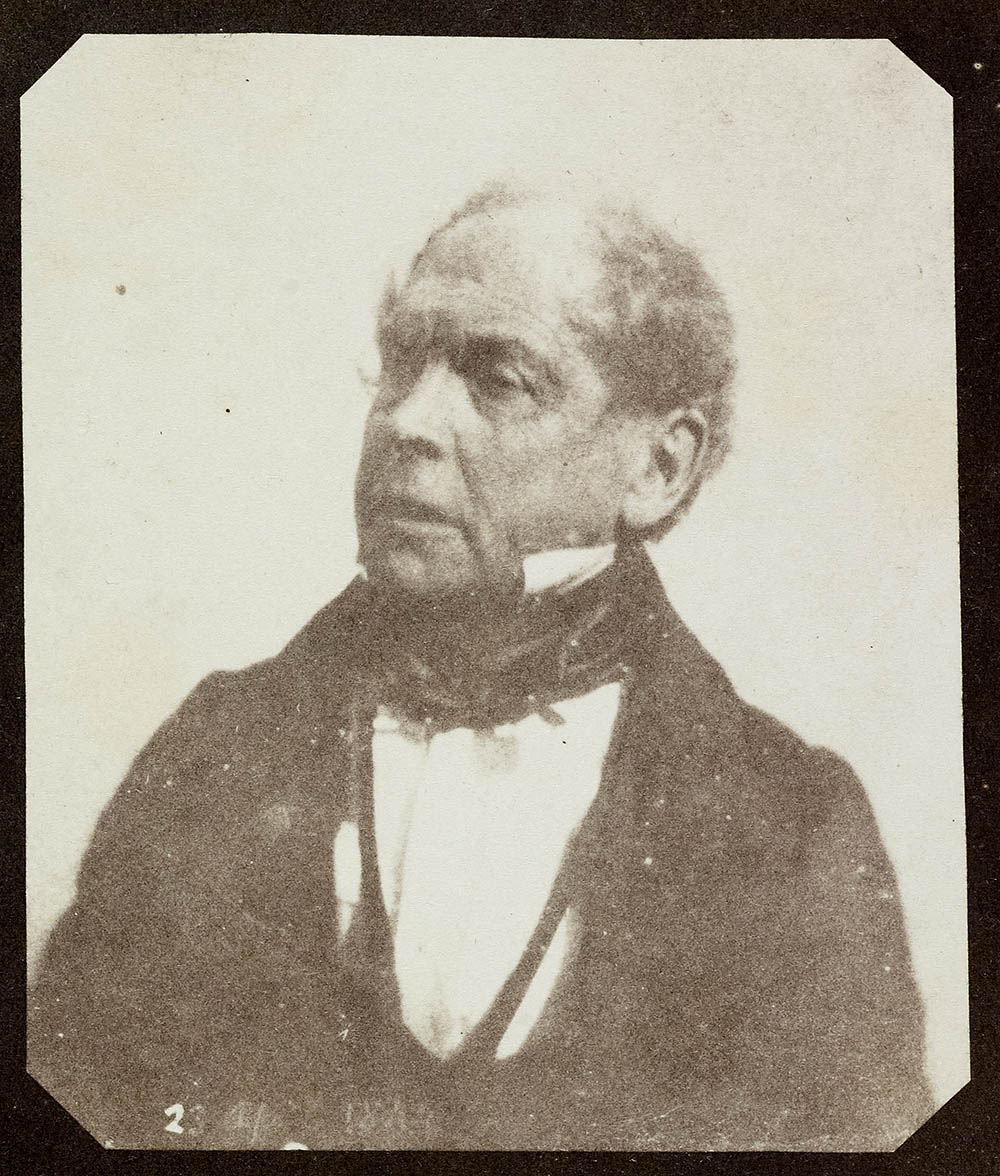

Clearly dated April 1844, the negative used to make this image was once identified with Sir David Brewster, who in fact visited Lacock Abbey that month. However, more recent scholarship has pretty solidly identified the top hatted man as Thomas Moore. The distinctive curls identify Horatia standing demurely to his left. Eliza Frayland, the nursemaid at the left, had come into the family’s employ with the birth of Charles Henry Talbot in 1842. Arranged in the front are Matilda Caroline ( later Gilchrist-Clark, age 5); Ela Theresa (age 9); Rosamond Constance Talbot (age 7). The woman at the right I am less sure about – can any expert identify her as Bessy Moore? On 23 April 1844 Moore recorded that “Bessy and I went to Lacock to join their family party – Lady Elisabeth not very well did not dine with us, and in the evening – Lady Mount Edgecumbe and Horatia arrived from Mount-Edgecumbe – 126 miles, and only a small portion of it rail-road – yet both as fresh in spirit and looks as if they had but arrive from next door.” Two days later he wrote “Bessy gave a dinner on our lawn to the Talbot’s children and Lady Kerry’s daughter, and nothing could be prettier – the young Talbots – at least three of them being beautiful children and the whole grouping together charmingly. Lady Lansdowne having heard of the intended fete sent down orders from town and we had flowers and fruit from Bowood in profusion.” So perhaps this portrait was taken at the Moore’s home of Sloperton Cottage, less than two miles from Lacock Abbey?

There is one clearly documented photographic effort done by Constance Talbot and happily it has a strong Thomas Moore connection. On 1 December 1843, she reported to Henry that “yesterday & today have been so very dark that Nichole [Nicolaas Henneman] has done nothing with the Camera though I believe he has been very busy other ways – and I saw the frames taking copies – Till yesterday the weather was very bright – I have seen the negatives of the Spanish views – & I thought they looked promising–I observed he had taken 2 of each subject, varying a little in depth of tint. – I have composed a little frame with the 4 first lines of the “Last rose of Summer” & it is now waiting for brighter weather.-” This is the longest statement that she ever made on the art of photography but the reference is clearly to the above images, undoubtedly executed as soon as the weather brightened. Photographic typesetting has been so common for so long that I suspect that many readers of the printed page do not give a thought to how Talbot’s invention made their book possible.

There is one clearly documented photographic effort done by Constance Talbot and happily it has a strong Thomas Moore connection. On 1 December 1843, she reported to Henry that “yesterday & today have been so very dark that Nichole [Nicolaas Henneman] has done nothing with the Camera though I believe he has been very busy other ways – and I saw the frames taking copies – Till yesterday the weather was very bright – I have seen the negatives of the Spanish views – & I thought they looked promising–I observed he had taken 2 of each subject, varying a little in depth of tint. – I have composed a little frame with the 4 first lines of the “Last rose of Summer” & it is now waiting for brighter weather.-” This is the longest statement that she ever made on the art of photography but the reference is clearly to the above images, undoubtedly executed as soon as the weather brightened. Photographic typesetting has been so common for so long that I suspect that many readers of the printed page do not give a thought to how Talbot’s invention made their book possible.

Finally, we turn to an enigmatic piece and I am going to crawl rather far out on a long springy limb on this one. Last week we saw that Moore had planned to transcribe two of his ballads for photographic inclusion in The Pencil of Nature. His perrenially popular ‘Remember the Glories of Brian the Brave’ would have been a natural choice to turn to in 1844. However, the first time I saw this lovely negative some years ago I immediately formed the feeling that not only was it early but that it was done by Constance Talbot. I cannot fully defend that attribution, but I do so vigorously and with conviction.

Finally, we turn to an enigmatic piece and I am going to crawl rather far out on a long springy limb on this one. Last week we saw that Moore had planned to transcribe two of his ballads for photographic inclusion in The Pencil of Nature. His perrenially popular ‘Remember the Glories of Brian the Brave’ would have been a natural choice to turn to in 1844. However, the first time I saw this lovely negative some years ago I immediately formed the feeling that not only was it early but that it was done by Constance Talbot. I cannot fully defend that attribution, but I do so vigorously and with conviction.

First of all, it seems improbable that this negative was ever intended for use as a master for The Pencil of Nature. Perhaps you have noticed already that the handwriting reads correctly left to right – it must have been produced from a manuscript whose paper had been oiled for transparency. However, as a negative to make multiple prints for the publication it would have been a puzzling choice. Prints from it would have looked like ink on paper but would have read backwards, surely some mental gymnastics that Talbot would not have wanted to inflict on his readership. Its lavender colour strongly implies that it was fixed – or really stabilised – with table salt, a method used by Talbot in the beginning. There was nothing to have prevented him from going back to this method in 1844. It was cheap and rapid in its action, but the additional exposure to sunlight needed to make prints from this negative would have destroyed it very quickly. One might argue that this was a quick proof to show to Moore, but then why oil the original manuscript first? And fixing it properly with hypo afterwards would have probably bleached the negative.

The salt fixing makes an 1839 (or earlier) dating more likely. We know that Constance did a little bit of experimenting in photography that year, her time and energy undoubtedly limited by the birth of their third daughter, Matilda Caroline, on 25 February. She mounted this negative in her personal album of watercolours and drawings that mostly date from the 1830s and 1840s. A few other artists are represented but the majority of the artwork is hers. There are two other photographs in the album, both presumably done by her husband, both later and both of their children. Whether done by Constance or by Henry, I think that this is an early merger of Talbot’s new art with Moore’s poetry. On 7 May 1839, probably just around the time that this negative was made, Moore recorded that “Bessy and I & Tom went over to Lacock for a couple of days – none but ourselves and their selves – not forgetting their pretty little children – Talbot took off several photogenic drawings for Bessy, during our stay.”

Larry J Schaaf

• Questions or Comments? Please contact digitalsupport@bodleian.ox.ac.uk • Very special thanks to Scott Docking of the Centre for Research Collections at the University of Edinburgh, without whom this posting would not have been possible. • WHFT, Portrait of Thomas Moore, salt print from a calotype negative, 23 April 1844; 1937-3838/2, National Media Museum, Bradford; Schaaf 2778. • Entry of 2 April 1828, quoted in The Journal of Thomas Moore, edited by Wilfred S Dowden (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1986), v. 3. The extensive contact between the Talbots, Feildings and Moores is best appreciated by consulting the comprehensive index at the end of the sixth volume. • Moore to James Powers, 4-30 April 1828, quoted in Notes from the Letters of Thomas Moore to His Music Publisher &c (London: T. Bosworth, 1853). • WHFT to Horatia Feilding, 29 August 1828, Talbot Correspondence Project Document no. 01706. • Elisabeth Feilding to WHFT, 9 October 1828, Doc. no. 01722. • Caroline Feilding, del., The Magic Mirror, published in Thomas Moore, Legendary Ballads, Arranged with Symphonies and Accompaniments (London: James Power, 1828), courtesy of Special Collections, Edinburgh University Library. • The Poetical Works of Thomas Moore (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1841); the tribute to Caroline is in v. 7, pp. 386-388. • WHFT, Legendary Tales, in Verse and Prose (London: James Ridgway, 1830). • Lady Elisabeth to WHFT, 25 February 1839, Doc. no. 01960; in defining the relationship between WHFT and his mother, this letter is well reading in its entirety. • WHFT, Portrait of Thomas Moore and Members of the Talbot Household, digital print from a calotype negative, April 1844, private collection. • Constance Talbot, Photographic Typesetting of Thomas Moore’s ‘The Last Rose of Summer, photogenic drawing negative and salt print. Negative, Fox Talbot Collection, the British Library, London, Acc 244; print, the National Media Museum, Bradford, 1937-2531-/36; Schaaf 3824. • Constance to WHFT, 1 December 1843, Doc. no. 05454. • • Attributed to Constance Talbot, Photographic copy of Moore’s manuscript of ‘Remember the Glory of Brian the Brave,’ photogenic drawing negative, 1839?, Fox Talbot Archive, the Bodleian Libraries, FT10338-38, Schaaf 4023. Another photograph in this album, that of Eliza Frayland with three Talbot children, is plate 51 in my Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot (Princeton, 2000).